Social Mobility, Religious Competition, and the Quest for Meaning

The Burned-Over District of upstate New York earned its evocative name from the “fires” of religious revival that swept repeatedly through the region in the early nineteenth century[^1]. In an era of rapid economic change and frontier expansion, this once-quiet corner of New York became a hotbed of spiritual upheaval. The Second Great Awakening’s flames burned so intensely here that observers quipped there was no “fuel” (unconverted souls) left – the area had been scorched by one revival after another[^2]. This chapter explores how unprecedented social mobility and intense religious competition combined to ignite individuals’ quest for meaning. We will examine the proliferation of new sects and deep theological rivalries that characterized the Burned-Over District, and analyze why such an extraordinary religious explosion occurred in the United States – especially in western New York. Ultimately, we consider what this peculiar flowering of faith says about American culture and religious psychology.

Image suggestion: A historical map of New York highlighting the “Burned-Over District” counties. Such a map helps situate the region where fervent revivals took root. In the early 1800s, western New York was a frontier zone being rapidly transformed by the construction of the Erie Canal (completed 1825) and the influx of migrants seeking new opportunities[^3]. Towns like Palmyra, Utica, and Rochester swelled in population and importance, creating a fluid social environment. This frontier-boom setting meant that many residents were recent arrivals with few established community ties or institutions. In this context of constant motion and settlement, old social hierarchies and traditions held less sway. The combination of mobility – geographic, economic, and social – and religious voluntarism (since no state church existed to dictate belief) created a freewheeling spiritual marketplace. Western New York became, in historian Whitney Cross’s words, a seedbed for “enthusiastic religion” where dozens of new denominations, sects, and utopian communities sprang up in close quarters[^4]. Amid this array of competing faiths, men and women faced pressing questions of identity, truth, and purpose. The Burned-Over District’s spiritual wildfires were fueled by people’s longing to make sense of their changing world and secure salvation in turbulent times.

Social Mobility and the Anxieties of Aspiration

One of the driving forces behind the revivals in the Burned-Over District was the era’s remarkable social and economic mobility. The early nineteenth century was a time when the rigid class structures of the past were loosening – especially on the American frontier. Ambitious individuals felt newfound freedom to rise in the world through hard work, trade, or entrepreneurial risk. The opening of the Erie Canal and the growth of market commerce meant that even a poor farmhand might become a prosperous shopkeeper or mill owner in a few years’ time[^5]. The possibility of upward mobility, however, carried with it intense anxieties. Could one truly improve one’s station, or would one fail and fall into ruin? How should a person balance the pursuit of wealth with moral integrity? Contemporary letters and diaries reveal that many Americans felt both excited and unnerved by the opportunities before them.

In a letter to a friend, a young settler in western New York expressed a mix of ambition and trepidation: “I am determined to rise in the world, to make a name for myself. But I am also afraid of failing – the thought of falling back into nothingness haunts me”[^6]. Such private confessions of hope and fear were common in the 1820s and 1830s as unprecedented avenues for advancement opened. The old certainties of a fixed social order were disappearing; individuals were left to forge their own destiny, which was both liberating and terrifying. The quest for material success thus often became intertwined with a quest for reassurance and meaning. If one achieved prosperity, did it signify God’s favor? If one struggled, was it a personal failing or part of a divine test? For many, the volatile swings of fortune demanded a spiritual explanation or anchor.

Revivalist religion offered exactly that anchor. Evangelical preachers in the Burned-Over District tapped into the hopes and fears of a socially mobile society. Charles Grandison Finney – the era’s most famous revival preacher – taught that salvation was within each individual’s grasp, much as success might be within reach in the worldly sphere. Finney rejected the old Calvinist notion of predestined fate; instead, he argued that each person had the free will to choose salvation and strive for holiness[^7]. This theological message resonated powerfully with Americans experiencing new freedom (and pressure) to shape their own lives. Finney’s revivals drew ambitious young strivers, anxious mothers, and aspiring merchants alike, all eager for guidance on how to live rightly and secure God’s blessing in unsettled times.

Importantly, revivalists like Finney reframed the very definition of “success.” In a society becoming ever more focused on commerce and wealth, ministers reminded people that moral and spiritual achievements mattered most. For instance, in an influential 1836 sermon titled “The Blessedness of Giving,” Finney cautioned his listeners not to measure their worth solely by financial gain[^8]. He preached that true success was not defined by the size of one’s bank account but by one’s upright character, generosity, and devotion to God’s work. If God had granted some believers prosperity, it was so they could do good – to help the less fortunate and further righteous causes – rather than indulge in greed. This message provided a reassuring moral framework for those unsettled by the competitive scramble for wealth. It taught that earthly achievements must be yoked to higher purpose. Converts were told that by living a godly life – being honest in business, sober and hardworking, kind to their neighbors – they could find a sense of security and honor that no economic crash or personal failure could take away. The revival experience thus helped many Americans channel their aspirations into a quest not just for status or riches, but for a meaningful life grounded in faith and virtue.

The social fluidity of the Burned-Over District also meant that traditional community bonds were weak, and individuals often felt adrift. Unlike in older towns where one’s identity and support network came from long-established family, church, and town ties, the rapidly growing communities of western New York were filled with newcomers. A farmer’s son could leave home and become a clerk in a canal town; a merchant from New England might set up shop in Rochester among strangers. In this context, the revival meetings themselves became important social events that forged new community bonds. As scores of people gathered under tents or in packed churches to sing hymns, pray, and weep together, they experienced an intense collective solidarity. One can imagine the comfort it brought to a young migrant or an upwardly mobile shopkeeper’s wife to suddenly be part of a warm fellowship of believers. The revival provided a ready-made community in a rootless society. Many converts testified that, upon conversion, they felt truly accepted and supported by their new church “family.” In short, the social upheavals of the time created a deep hunger for belonging – a hunger that revivalist religion was uniquely positioned to satisfy.

Religious Competition in the Burned-Over District

If social mobility primed people’s hearts for revival, it was the fierce religious competition in the Burned-Over District that ensured nearly everyone would encounter some compelling vision of faith. The disestablishment of state religion in America (cemented by the First Amendment) meant that no single church or denomination held a monopoly. Every religious group had to win over adherents by persuasion and zeal rather than relying on government support. Nowhere was this pluralistic free-for-all more evident than in western New York, where by the 1830s an observer could find a patchwork of Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Quakers, and more – all vying for souls. Moreover, the region incubated a host of new religious sects led by charismatic lay preachers, each proclaiming a special message or restored truth. One scholar noted that by the mid- nineteenth century, dozens of distinct sects had emerged in the Burned-Over District, each insisting that it alone possessed the true path to salvation[^9].

The competition among churches took many forms. Established Protestant denominations like the Congregationalists and Presbyterians, which had long dominated New England, suddenly found themselves challenged by upstart groups. The Methodist Episcopal Church, for example, was growing explosively on the frontier thanks to its energetic circuit-riding preachers who brought lively camp-meeting revivals to even the most remote hamlets. Baptist preachers likewise roamed the region, founding little congregations based on adult baptism and simple, emotional worship. These evangelical newcomers often attracted the common folk more effectively than the staid old churches with their learned (but sometimes aloof) clergy. The result was a democratization of Christianity: ordinary farmers and artisans often preferred religious gatherings led by lay exhorters who spoke their language, rather than formal liturgies led by college-educated clergymen. In the Burned-Over District, an everyday laborer might preach under a brush arbor one week, while a Yale-educated reverend delivered a sermon in a village church the next – and locals would decide whose message moved them more.

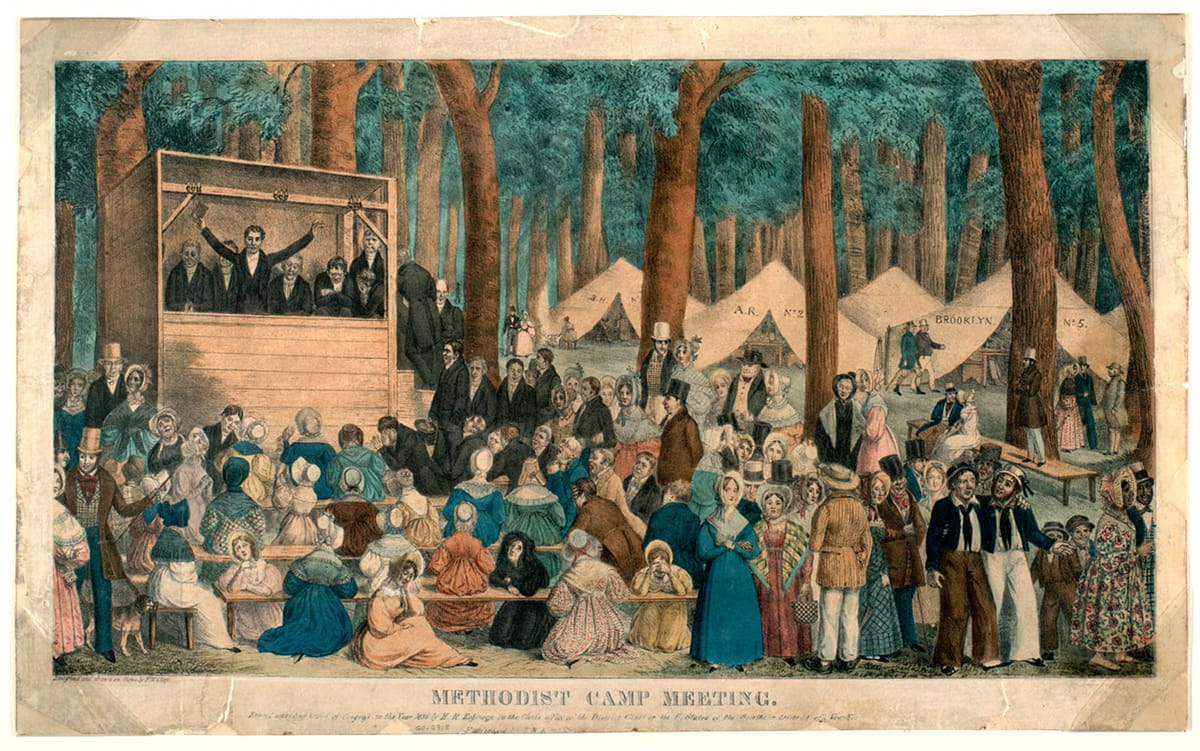

The ferment of competing preachers created a veritable marketplace of faith. Just as new businesses in canal towns competed for customers, new churches and sects competed for converts. Camp meeting revivals were one battleground of this competition. Different itinerant ministers would organize huge outdoor meetings that drew people from miles around with the promise of powerful preaching and the possibility of miraculous conversion experiences. These multi-day gatherings often featured preachers from various denominations, sometimes preaching in succession or even simultaneously at opposite ends of a large campground. One report from a camp meeting in western New York in the 1820s described “a dozen ministers, of nearly as many sects, holding forth at once… so that a person might wander from one impassioned exhortation to another all through the night”[^10]. In this cacophony of competing sermons and songs, attendees could essentially sample different religious styles and doctrines. The din of voices crying out earnest appeals – some thundering about hellfire, others extolling God’s love – created an atmosphere in which individuals were challenged to discern the true path among many.

Not only were mainstream churches competing – new sects were springing up, each adding to the rivalry. The Burned-Over District’s legacy is famously tied to the birth of several new religious movements that would leave a lasting mark on American history. Among these were the Mormons, the Millerites, the Shakers, the Spiritualists, and others – all of which either originated in western New York or found fertile ground there. Each sect claimed a unique truth or revelation that set it apart from the others, leading to sometimes bitter disputes.

For example, in the late 1820s a young man named Joseph Smith in Palmyra, NY grappled with the bewildering array of churches around him. He later described how “the Presbyterians were most decided against the Baptists and Methodists, and used all the powers of either reason or sophistry to prove their errors,” while each group in turn insisted it alone was right[^11]. This “war of words and tumult of opinions,” as Smith called it, left him deeply confused about which church, if any, taught the true gospel[^11]. His personal quest for an answer led to the founding of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormon Church) in 1830. The Mormon movement, born in the Burned-Over District out of Smith’s visionary experiences, boldly declared that all existing sects were in apostasy and that God had chosen America as the place to restore the true Church. Such a claim did not sit lightly with the established clergy of the area – Mormon missionaries and believers soon met with intense opposition and even mob violence, driven in part by rival preachers who denounced them as heretics. Yet the movement continued to draw converts hungering for a clear, prophetic message in an age of uncertainty. By offering new scripture (the Book of Mormon) and a restored vision of primitive Christianity, Mormonism appealed to those disillusioned by the cacophony of contending sects. In effect, Joseph Smith turned the era’s religious competition to his advantage: he presented a faith that cut through the competing claims by declaring a new, divine authority that stood above debate.

Another major new movement, the Millerites, arose a bit later with a very different focus: predicting the imminent end of the world. William Miller, a farmer from upstate New York, became convinced through careful Bible study that Christ would return around 1843–1844. He began preaching this message in the 1830s, gaining a wide following across the Burned-Over District and beyond. Miller’s followers, drawn from various denominations, fervently believed they had discovered a unique truth that other churches ignored – namely, the exact timing of the Second Coming. They eagerly circulated charts and tracts decoding biblical prophecies and held enthusiastic camp meetings to warn everyone to repent before the great day arrived. As the predicted date (October 22, 1844) approached, tensions between Millerites and other Christians grew. Many traditional ministers condemned Miller’s calculations as speculative at best and fanatical at worst. Some congregations even expelled members who openly embraced Miller’s teachings, considering them misled. The Millerites in turn accused mainstream churches of being blind to urgent prophetic truth. This theological rivalry reached its climax in the Great Disappointment of 1844, when Christ did not visibly return as expected. In the aftermath, most Millerites were left crestfallen and many drifted away, but a core remnant regrouped and eventually gave rise to new sects (such as the Seventh-day Adventists) that persisted in modified form. The Millerite episode highlights how the Burned-Over District’s climate of fervent expectation and competition could produce dramatic swings – from ecstasy to despair – in the spiritual lives of those seeking certainty.

The Shakers provide another fascinating example. Led by Mother Ann Lee (who had arrived in New York from England in the late 1700s), the Shakers established communal villages in New York and New England based on celibacy, shared property, and ecstatic worship. By the 1820s and 1830s, Shaker communities dotted parts of western New York, and their reputation for strange practices (like dancing in worship and strictly segregating the sexes) made them both famous and controversial. The Shakers claimed to be restoring the true apostolic church by living like the earliest Christians described in Acts – holding all things in common and awaiting the imminent fulfillment of God’s kingdom. They believed Ann Lee was a prophetess, even a female embodiment of Christ’s spirit. These were radical claims that put them at odds with all other Christian groups in the area. Yet, in the competitive spiritual marketplace, the Shakers drew a following, particularly among those dissatisfied with mainstream churches’ worldliness. Outsiders were intrigued by Shaker teachings on simplicity and equality (including equal leadership roles for women), even as most could not accept their stringent celibacy. Here again, the Burned-Over District’s ethos meant that a small sect with unorthodox beliefs could not only survive but flourish for a time, actively proselytizing and drawing converts in the region. Other sects, such as the followers of the self-declared prophetess Jemima Wilkinson (the Public Universal Friend) a bit earlier, or the rise of Spiritualism in 1848 (sparked by the Fox sisters’ claimed spirit communications in Hydesville, NY), further exemplified this pattern. Each group passionately believed it had tapped into ultimate truth, and each had to assert itself against a backdrop of rivals eager to dismiss or outshine it.

This climate of religious rivalry did not go entirely unnoticed or uncriticized by contemporary observers. While many everyday people were caught up in choosing sides, some leaders worried about the chaos of competing doctrines. In 1833, a committee of the Methodist Episcopal Church’s Oneida Conference (covering part of the Burned-Over region) lamented that the proliferation of itinerant preachers and conflicting teachings was causing confusion. Their report complained that the variety of enthusiastic revival services “must unsettle and confuse our society, and expose our sacred doctrines to the ridicule of our enemies”[^12]. In other words, even some revival-friendly clergy feared that too much competition – too many zealots each pushing their own version of the gospel – could discredit Christianity as a whole. Established ministers often struggled to maintain authority and order when lay exhorters and radical prophets were drawing crowds next door. The Second Great Awakening, especially in upstate New York, thus had a fracturing effect on American Protestantism: it shattered the hold of any one church over the community and replaced it with a cacophony of voices. In the long run, this led to an extraordinary pluralism – a permanent state of religious diversity in America – but in the moment, it could feel like turbulent fragmentation.

The Quest for Meaning Amidst Upheaval

Why did so many people in the Burned-Over District respond to these religious movements? To outsiders, some of the new sects and revival phenomena seemed bizarre or extreme. Yet, for those living through the upheavals of that era, the intense religious activity was driven by a profound quest for meaning. Traditional sources of meaning – like longstanding communities, stable family lineage, or a single inherited church affiliation – had been upended for many frontier Americans. In their place, individuals grasped for new anchors to make sense of life’s purpose and their own identity.

Religious conversion during the Second Great Awakening was often a deeply existential experience. Contemporary conversion narratives from western New York reveal people wrestling with questions of sin, salvation, and significance. In revival meetings, attendees felt their hearts “pricked” by sermons that asked, in essence, What are you living for? and Are you right with God? A farmer’s wife might suddenly see her daily toil in a new light – as part of a divine calling to raise a godly family. A young merchant, anxious about the ruthlessness of business life, might find peace in the idea that true riches were spiritual and everlasting. Over and over, converts described feeling a heavy burden lifted from their shoulders at the moment they “gave their heart to Jesus.” That burden was not only the weight of sin, as preachers would phrase it, but also the weight of uncertainty – uncertainty about one’s worth, one’s fate, and the chaotic world around. By accepting a religious conversion, individuals often discovered a newfound sense of purpose and worth. They came to believe that they were chosen by God, that their lives had a higher meaning in the grand scheme of salvation. This was incredibly empowering in a society where so many felt insignificant or lost.

Consider the example of the early Mormon converts. Many of Joseph Smith’s first followers in New York were poor farmers or young laborers who had been marginal in the social order. Embracing the new faith suddenly gave them a thrilling sense of participating in divine history. They referred to themselves as “saints” and believed they were building Zion, God’s kingdom on earth, in preparation for Christ’s millennial reign. To these men and women, joining the Mormon movement transformed mundane lives into epic narratives; they became pioneers not just in a westward expansion, but pioneers of the Lord’s new kingdom. Similarly, those who joined the Millerite movement found intense meaning in expecting Christ’s return. One Millerite diarist wrote in 1843 that although she had little property or status in this world, it didn’t matter because “We know the Lord is at hand; we are but strangers here. Our treasures are in Heaven, and soon we shall meet Him in glory”[^13]. This apocalyptic hope gave ordinary people a powerful psychological boost: their struggles and sacrifices were temporary, and a glorious resolution was imminent. Even after the Great Disappointment, many clung to the conviction that they were living in sacred time, that their vigilant faith made them special participants in God’s unfolding plan.

For those who gravitated to more radical experiments like the Shakers or the Oneida Community (a utopian communal group established in 1848 in Oneida, NY), the quest for meaning took the form of reinventing societyaccording to divine principles. The Oneida perfectionists led by John Humphrey Noyes believed that the Second Coming had already occurred in a spiritual sense, and therefore humans could strive for perfect holiness and even create heaven on earth through communal living and unconventional marriage practices. It is difficult to imagine people embracing such dramatic departures from mainstream life – giving up private property, traditional monogamy, etc. – unless they were deeply motivated to find transcendent purpose. Indeed, many who joined these communities spoke of dissatisfaction with the hollow materialism or competitive individualism they saw in American society. The religious utopias offered an alternative value system and a chance to imbue every aspect of daily life with spiritual significance(from farming together for God’s glory, to treating all members as one family in Christ). Such meaning-rich environments appealed to those yearning for a life that mattered, in stark contrast to the dog-eat-dog world outside.

Even within the more conventional revivals led by Finney and others, the quest for a personal connection to the divine was paramount. The revivals emphasized that each soul mattered immensely – an idea with revolutionary implications for the common person. Unlike older Calvinist theology which might have left people wondering if they were predestined to damnation or salvation, the new revivalism said God cared and that you could actually sense His love and direction in your life. The use of the “anxious bench” (where repentant seekers came forward publicly to be prayed for) and the sharing of personal testimonies during meetings reinforced that religion was not just about dusty doctrines, but about one’s inner journey and lived experience. Converts frequently described a newfound intimacywith God – they spoke of Jesus as an ever-present friend and of the Holy Spirit as a felt comforter guiding their daily decisions. In a time of so much external change, this inner, heartfelt religion provided a stable core of meaning. It promised that, no matter what happened in the economy or on the frontier, one’s relationship with God was a secure rock on which to stand.

The Burned-Over District revivals also engaged the moral imagination of participants. The quest for meaning often manifested as a passion to do good in the world, to align one’s life with higher moral purposes. Many revival converts threw themselves into the great reform movements of the day – temperance (combating alcohol abuse), abolitionism (the anti-slavery cause), and others – seeing these as extensions of God’s will. In western New York, evangelical fervor and social reform went hand in hand. For instance, Charles Finney himself was a staunch abolitionist who thundered against slavery from the pulpit; he and his converts in places like Rochester helped turn that region into a center of anti-slavery activism[^14]. To these believers, fighting injustice and helping the downtrodden was part of their religious calling – a way to make their faith meaningful in action. This blending of personal salvation with social mission further fulfilled the search for meaning: converts were not only saving their own souls but also redeeming the nation. Such grand purpose could make even the humblest person feel like an agent of God’s work in the world.

In sum, whether through the intensity of a conversion experience, the embrace of a millenarian timeline, participation in communal utopias, or engagement in reform, people of the Burned-Over District found myriad ways to satisfy their craving for meaning. The key was that the religious movements of the time met individuals where they were: addressing their hopes, fears, and aspirations in a rapidly changing society. Each sect or denomination offered its adherents a framework to interpret their lives – to answer the pressing questions: Who am I? Why am I here? What is the right path to take? The sheer number of answers on offer was itself a product of American freedom, and those answers resonated because they spoke to real emotional and spiritual needs.

American Innovations in Faith: Why Here, Why Then?

It is no accident that the spiritual wildfire of the Second Great Awakening burned brightest in the United States, and particularly on the frontier of New York. The phenomenon was rooted in distinctly American conditions that favored religious innovation. Foreign visitors in the 1830s often remarked on the unique religious culture of the United States. Unlike in Europe – where centuries-old state churches still dominated and enforced a measure of uniformity – America was seen as a land of religious freedom and fervor. Alexis de Tocqueville, the French observer of American life, was astonished to find that religion thrived in the United States precisely because it was voluntary and decentralized. Far from diminishing faith, the separation of church and state had unleashed a competitive energy among sects, which in turn produced high levels of popular piety. Tocqueville wrote that in America, “the spirit of religion and the spirit of liberty” were intimately entwined, each bolstering the other[^15].

The Burned-Over District exemplified how the democratic ethos of the new nation transformed the religious landscape. Traditional religious authority was suspect in this environment – what mattered was results (i.e. converts, changed lives) and a persuasive message that appealed to the common man or woman. If one preacher or church wasn’t meeting people’s needs, another would arise that did. This was analogous to the free market of the economy: competition spurred innovation. Historians have noted that early 19th-century America saw a remarkable breakdown of old ecclesiastical monopolies and the rise of popular sect leaders with little formal training[^16]. In the Burned-Over District, many influential figures were self-made prophets. Joseph Smith was a farm boy with a grade-school education; William Miller was a self-taught Bible enthusiast; the Fox sisters, who launched Spiritualism, were teenage girls. None of these would-be visionaries had any place in the religious establishments of Europe or colonial America – but on the democratic frontier they could each find an audience. As one study observes, “almost all the radical innovators were laypersons with little or no theological training – William Miller, Joseph Smith, Mother Ann Lee, Jemima Wilkinson, et al. – a testament to the openness of the American religious scene to charismatic outsiders”[^16]. In short, the United States provided an ideal incubator for new religious movements: a society that valued individual inspiration over credentialed tradition, that allowed any gathering of believers to call itself a church, and that protected the rights of even eccentric sects to preach openly.

Economic factors also played a crucial role. The market revolution was in full swing in the Burned-Over period, meaning not only were goods and commerce rapidly expanding, but ideas and information were as well. Improvements in printing technology and transportation (like canals and post roads) meant that a traveling preacher’s message could be spread widely through cheap pamphlets and frequent news reports. Upstate New York in the 1830s had an abundance of local newspapers that eagerly covered the sensational happenings of revival meetings and new prophets. This media coverage created a kind of feedback loop: the more people read about revival fervor or controversial sects, the more curious they became and the more likely to attend the next meeting. In a sense, religion became news, and news helped religion spread. Furthermore, the burgeoning American ideal of progress – the notion that society was advancing and the frontier was the vanguard of civilization – gave a certain optimism to religious innovators. Many believed that they were not just reacting to change but actively ushering in a new, more enlightened age of Christianity. The Millerites explicitly thought they were announcing the ultimate culmination of history; Finney believed he was helping to bring about the millennial kingdom through conversions and moral reform; other sects talked of restoring original Christianity in a purer, improved form. This forward-looking, entrepreneurial spirit meshed perfectly with American culture. Just as an inventor or entrepreneur might start a new enterprise on the frontier, an evangelist could start a new denomination. The barriers to entry were low – one needed only a Bible, conviction, and a willingness to face ridicule or opposition.

Why specifically western New York? Here, several unique streams converged. First, the region’s population in the early 1800s was disproportionately made up of transplanted New Englanders – people who had grown up with the Puritan-influenced religious tradition that valued Bible study, moral seriousness, and communal covenant. When they moved to New York’s frontier, these Yankees brought with them a cultural predisposition toward religious concern, but without the institutional restraints of their old town parishes. It was a perfect recipe for religious experimentation: they had deep faith interests but were cut loose from the oversight of established pastors and churches. Second, as noted earlier, the Erie Canal boom created prosperity and social dislocation; places like Rochester saw explosive growth, which tends to disrupt older social controls (like close-knit communities where everyone watches everyone). Revivalism often thrives in such fluid settings, where people are making choices about affiliation. Third, some historians have pointed to burnout and soil exhaustion in New England which pushed young people to migrate west, carrying with them a certain disillusionment or spiritual yearning that made them receptive to revivalist appeal[^4]. In fact, the term “Burned-Over District” itself implies that the region had seen so many waves of revival that an ever-more spectacular fire was needed to catch attention – which could encourage preachers to escalate tactics and teachings, possibly contributing to the rise of more radical sects after the initial revivals.

Finally, it is worth considering an intangible but important factor: the American religious psyche of the era. Americans of the early republic had imbibed ideas of liberty, individual rights, and the pursuit of happiness. Applied to religion, this translated into a kind of spiritual individualism – a sense that one had not only the right but perhaps the duty to seek a personal understanding of God and truth. The idea of blindly following the religion of one’s fathers was less compelling in a nation that so emphasized personal choice and conscience. This attitude can be seen in countless conversion stories of the time, where the individual narrates how they questioned what they had been taught, explored the scriptures themselves, and ultimately made their own decision for Christ (or, in the case of sectarians like early Mormons, for a new revelation). In America, religion became, in a way, self-directed. The plethora of denominations was both cause and effect of this mindset: people shopped for a church that resonated with them, and churches in turn adapted to attract people. Europe, in contrast, retained more of a collectivist religious culture in which one’s identity was tied to national or ethnic church traditions, making it harder for new sects to break through. Thus, the American emphasis on the freedom to find one’s own path was a critical ingredient in the Burned-Over District’s explosion of religions. It created a climate where thousands felt emboldened to join a revival, or leave an old church, or even start a brand-new faith community – all in the name of fulfilling their personal quest for religious meaning.

Reflections on American Culture and Religious Psychology

The story of the Burned-Over District holds up a mirror to enduring aspects of American culture and the national psyche. It reveals Americans as a people profoundly yearning for meaning, open to innovation, and comfortable with a high degree of religious pluralism (even as each group may claim exclusive truth for itself). There is a certain irony in that comfort with pluralism: on one hand, the various sects were often at each other’s throats doctrinally; on the other hand, American society as a whole managed to accommodate this diversity without rupturing. In the competitive “market” of faith, each sect had to learn to coexist with its rivals in the long run, leading to a kind of grudging tolerance. This set the stage for a broader American principle of religious freedom and separation of church and state – a pragmatic acceptance that many religions will flourish and none can wipe out the others. Thus, one legacy of the Burned-Over District is the notion that religious diversity is normal in America. The region was an early microcosm of the nation’s future, where Baptists and Millerites, Shakers and Methodists all had to live side by side. Over time, that pluralism only increased. By the late 19th and certainly the 20th century, the United States would become home to an ever-expanding array of denominations and faith movements, a trend that continues today (with thousands of distinct Christian denominations in America and around the world[^17]). The roots of that proliferation trace back to the freewheeling, entrepreneurial religious culture that places like western New York pioneered.

American religious psychology, as evidenced in the Second Great Awakening, also seems to exhibit a pendulum swing between individualism and community. On the frontier, the individual’s right to believe as he or she chose was paramount – yet the longing for community drove people to form new groups to share those beliefs. This dynamic suggests that Americans solve the tension between individual freedom and collective belonging by creating voluntary communities (churches, sects, movements) that one can join or leave without state coercion. In the Burned-Over District revivals, when one community or denomination didn’t meet a person’s needs, they felt free to seek or even establish another. This fosters a kind of continuous religious reinvention that has marked American history. New revivals and religious “awakenings” have recurred in the United States (e.g., the Azusa Street Revival birthing Pentecostalism in the early 1900s, the rise of new religions and New Age movements in the later 20th century) in a pattern reminiscent of the Burned-Over District. Each time, social changes (urbanization, globalization, etc.) create anxieties and hopes, and Americans respond by generating new religious responses or reviving old ones in novel forms.

Another critical reflection is on the optimism and idealism inherent in these movements. Americans in the Burned-Over District displayed an extraordinary confidence that ultimate truth was knowable and that society could be perfected (or at least improved drastically). This is a cultural trait that observers have long noted: a kind of can-do idealism applied to matters of the soul. Rather than accepting a tragic or fixed view of human nature, revivalists preached the possibility of personal and social transformation. Drunkards could become sober, the unjust could become righteous, and the fragmented church could become whole (or be supplanted by a restored true church). Even the impulse to predict Christ’s exact return speaks to a bold willingness to pursue knowledge of divine mysteries, a mindset not typically embraced in older, more tradition-bound cultures. One might say there is an element of spiritual boldness – even audacity – in the American approach to faith. The Burned-Over enthusiasts were unafraid to proclaim new doctrines, start new communities, or testify to dramatic emotional experiences. That openness to religious emotion and experiment speaks to an American psychological readiness to engage the sacred on very personal terms. While this produced some excesses and disappointments (as critics at the time and since have noted), it also gave American religion a resilience and creativity that continues. Where others might grow cynical after a failed prophecy or a fallen prophet, Americans have often responded by either reforming the movement or moving on to the next inspiration, rather than abandoning faith entirely.

Of course, the Burned-Over District also highlights a darker side of religious fervor: the propensity for conflict and disillusionment. For every person whose life was enriched by finding a satisfying faith, there was someone else perplexed or even harmed by the strife of sectarian competition. Families could be split when one member ran off to join a sect others found abhorrent; communities could be divided by rival revivals; some individuals fell into despair when a much-hoped-for miracle did not occur. American culture’s encouragement of religious experimentation meant there were relatively few external checks on charismatic leaders or fringe doctrines. Sometimes this led to what later observers would call fanaticism or cults. The case of the Millerites, for example, invited a backlash of ridicule from skeptics after 1844 – a salutary reminder that unbridled enthusiasm can curdle into cynicism. Indeed, the phrase “burned-out” could also describe those left exhausted or skeptical by too many failed prophecies or manipulative preachers. American religious psychology thus encompasses both the credulity that fosters new movements and the doubt that inevitably follows when some of those movements falter. The cycle of revival and backlash is another pattern that the Burned-Over District foreshadows in U.S. history.

In conclusion, the Burned-Over District and the Second Great Awakening in which it played a starring role demonstrate how social mobility, religious competition, and the quest for meaning converged to create a uniquely dynamic religious culture. This fertile ground produced new faiths that have endured (such as the Mormon church and Adventist movement) and a legacy of revivalism that influences American evangelicalism to this day. It happened in America – and particularly in upstate New York – because of American ideals of freedom, democracy, and progress that penetrated even the realm of the spirit. The “land of opportunity” was not just about economic opportunity; it was about spiritual opportunity as well. In the Burned-Over District, Americans proved adept at seizing that opportunity: forging paths to God as boldly as they forged westward trails, pursuing salvation with the same enterprise they pursued success. The myriad sects and theologies that sprang up were, in a sense, experiments in meaning-making. They tell us that American culture has long harbored a vibrant strain of restlessness of the soul – a refusal to be satisfied with inherited answers, a drive to seek something more. And when that restlessness is combined with a free, competitive environment, the result is an outpouring of religious creativity unmatched in scope. The Burned-Over District’s fiery crusade for faith thus speaks volumes about the American soul: ever in search of renewal, ever confident that somewhere just ahead lies the ultimate revival of fire and spirit that will make all things new.

[^1]: The term “burned-over district” was popularized by revivalist Charles G. Finney in his 1876 memoir, referring to western New York communities repeatedly scorched by revivals until no “unconverted” fuel remained. See Charles G. Finney, The Autobiography of Charles G. Finney (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1876), 78.

[^2]: Whitney R. Cross, in his seminal study The Burned-over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York, 1800–1850 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1950), details the successive waves of revival that swept the region. See Cross, 3–4. An observer in 1831 noted the region seemed to catch “fire” with revival zeal every few years (Cross, 14).

[^3]: For background on the Erie Canal’s impact and the social transformation of western New York, see Milton Klein, The Empire State: A History of New York (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001), 301–305. The canal’s opening unleashed rapid commerce and migration, contributing to fluid class and community structures.

[^4]: Cross, The Burned-over District, 7–15. Cross enumerates the many sects and reform movements emerging from the region’s “spiritual soil,” from Millerites and Mormons to abolitionists and communal societies, all fueled by an enthusiastic religious temperament.

[^5]: Paul E. Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, New York, 1815–1837 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978), 20–36. Johnson describes how Rochester’s burgeoning market economy created new opportunities for wealth as well as social instability, a context in which revivalism took on particular urgency.

[^6]: James Fenimore Cooper to William Branford Cooper, 1828, in Cooper Family Papers, New-York Historical Society. (Cooper, best known later as a novelist, here writes as a young man expressing personal ambition and fear of failure. The letter offers a window into the mindset of aspiring Americans in the 1820s.)

[^7]: Charles G. Finney’s theology of free will and human agency in salvation is outlined in his Lectures on Revivals of Religion (Boston: Leavitt, 1835). Finney taught that “sinners have the natural ability to turn to God” and that revivals are the predictable result of proper use of means, rather than mysterious acts of providence (Finney, Lectures, 10–12).

[^8]: Finney’s sermon “The Blessedness of Giving” (1836) is quoted in The Evangelist (New York), May 1837, 1. In it, he warns against the “love of gain” and extols charitable giving as the true measure of success in God’s eyes. Finney often preached on practical Christian duties, linking personal piety with social ethics.

[^9]: An account of the region’s religious diversity is given in John H. Martin, “Religious Vitality and Diversity in the Burned-Over District,” in New York History, vol. 65, no. 1 (1984), 61. Martin notes that by 1850 nearly 100 different religious sects or denominations could be identified in upstate New York.

[^10]: Quoted in Cross, The Burned-over District, 20. Cross cites a contemporary description of a camp meeting near Rome, NY, illustrating the simultaneous preaching and “babel of voices” from various exhorters that typified these gatherings. Such accounts underscore the competitive atmosphere as different preachers vied for the crowd’s attention.

[^11]: Joseph Smith, Joseph Smith–History 1:8–10, in The Pearl of Great Price (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1981). In this autobiographical narrative, first written in 1838, Smith recounts the contentious revival climate around Palmyra, NY circa 1820 that spurred him to seek divine guidance (“the tumult of opinions … I often said to myself: What is to be done? Who of all these parties are right, or are they all wrong together?”).

[^12]: “Report of the Committee on the State of the Church and the Discipline” (1833), Oneida Conference, Methodist Episcopal Church – Archives, Syracuse University. The committee expressed concern that irregular revival practices and a proliferation of itinerant exhorters were sowing confusion and inviting public mockery of the church.

[^13]: Diary of Dorothy Miller, July 1843, reprinted in Clyde P. Taylor, The Millerite Spirit: Essays on the Second Advent Movement (Boston: Beacon Press, 1972), 114. Miller, a Millerite devotee in western New York, articulates her heavenly hope and detachment from worldly pursuits in anticipation of Christ’s return.

[^14]: R. Lawrence Moore, Religious Outsiders and the Making of Americans (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 27–30. Moore discusses how Finney’s revivalism in upstate New York linked with social reform, particularly abolitionism – in 1837 Finney publicly refused Communion to slaveholders, an unusually strong stance for clergy of that time.

[^15]: Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. George Lawrence (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), 295. Tocqueville observed that “Religion in America takes no direct part in the government of society, but it must be regarded as the first of their political institutions… I do not know if all Americans have a sincere faith in their religion – but I am certain that they hold it to be indispensable to the maintenance of republican institutions.” He noted the voluntary vigor of American religious life, in contrast to Europe.

[^16]: Nathan O. Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 9–12. Hatch emphasizes that the early nineteenth century saw a revolution in religious authority, as self-taught preachers and prophets arose from the masses, eroding the dominance of educated elites in the churches. This trend was especially pronounced on the frontiers.

[^17]: David B. Barrett, et al., World Christian Encyclopedia, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 12. Barrett’s survey famously estimated over 33,000 Christian denominations worldwide at the turn of the 21st century (a number that has only grown since). While definitions of “denomination” vary, the point remains that the United States – as one of the most religiously diverse and fissiparous societies – has been a primary generator of new sects over the past two centuries.