Dressed to Kill: The Allure and Agony of Arsenic Green in 19th-Century Fashion

A Color to Die For

Imagine a grand ballroom in the 1860s, illuminated by the soft glow of gaslight. Amidst the swirl of silks and satins, one color electrifies the scene: a brilliant, jewel-toned emerald green. A woman adorned in a gown of this magnificent hue is the envy of the room, her dress a testament to both wealth and high fashion. Yet, with every graceful turn in a waltz, she unknowingly sheds a fine, invisible dust—a glittering cloud of poison. This scene, a blend of glamour and horror, captures the central paradox of one of the 19th century's most dangerous fashion trends. The very color that symbolized life, nature, and springtime vitality was, in fact, a harbinger of sickness and death.1

This is the story of arsenical green, a pigment born from the crucible of the Industrial Revolution that promised a world of vibrant color but delivered a hidden plague. It is a cautionary tale of scientific innovation outpacing public safety, of consumer desire overriding common sense, and of the devastating human cost of beauty. This report, drawing exclusively on the primary accounts of the era—from chemical treatises and medical journals to popular magazines and the impassioned words of social reformers—will explore the science behind this killer color. It will chronicle the immense suffering of those who made it and those who wore it, listen to the voices that cried out in warning, and trace the trend's eventual decline. Finally, it will follow these deadly garments into their modern afterlife, where they rest behind museum glass, their toxic legacy carefully contained but never forgotten.

Part I: The Birth of a Brilliant Poison

The Tyranny of Muted Hues: The Pre-Industrial Palette

To comprehend the sensational success of arsenical green, one must first understand the world of color that existed before it. In the pre-industrial era, textile dyeing was an arduous and expensive craft.3 Dyes were derived from natural sources—plants, insects, and minerals—and producing vibrant, lasting colors was a mark of exceptional skill and wealth.4 Many natural dyes yielded colors that were muted, faded quickly with sun exposure, and washed out over time.3

Green was notoriously difficult to master. It was rarely achieved with a single dye but instead required a complex, two-step process: fabric was first dyed yellow and then over-dyed with blue.3 This was an imperfect and laborious solution. A single mistake in either step could ruin the final color, and achieving consistency across multiple batches was a true feat of the dyer's art.3 Consequently, a brilliant green fabric was a luxury of the highest order, often restricted by cost or even sumptuary laws to the upper echelons of society.3 As one historian vividly illustrates, "Robin Hood and his merry men did not dress in green for camouflage, quite the opposite; they wore green to throw their stolen wealth in the faces of the Nottingham nobles they stole from".3 This pre-existing cultural value—green as a symbol of status and wealth—created a fervent market, primed and waiting for a technological breakthrough that could democratize this coveted color.

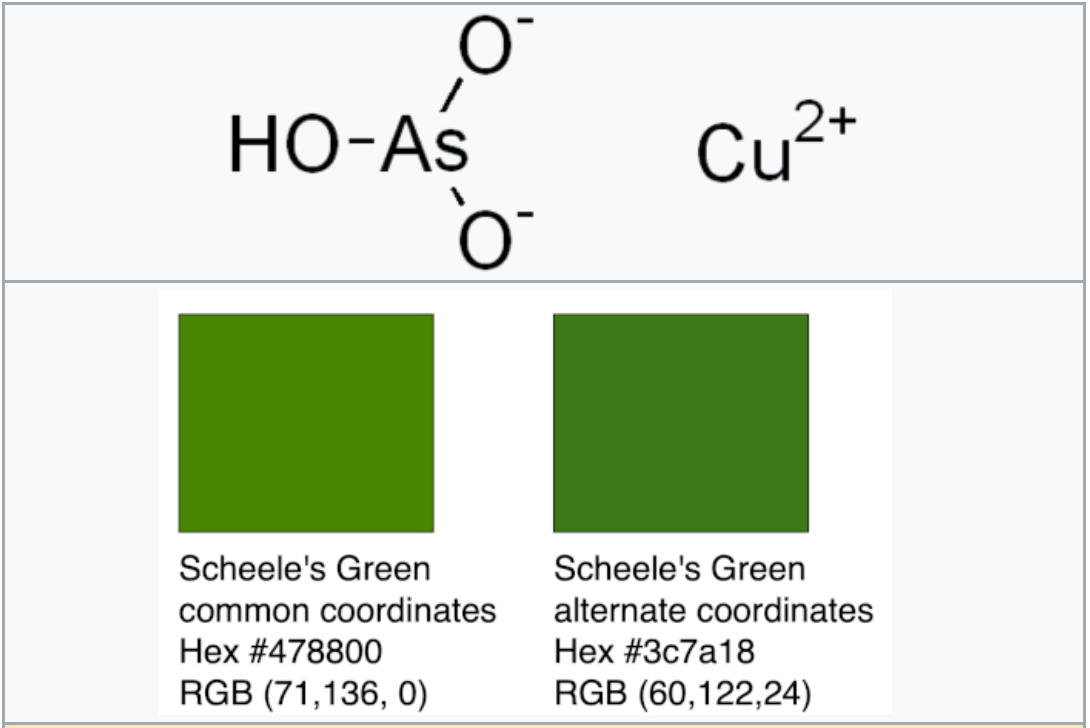

A Chemical Marvel: The Invention of Scheele's and Paris Green

That breakthrough arrived in 1775. The Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele, a brilliant scientist credited with the co-discovery of oxygen, was experimenting with the toxic element arsenic when he created a startlingly vibrant green pigment.1 Known as Scheele's Green, or Schloss Green, it was chemically a cupric hydrogen arsenite, with the formula

CuHAsO3.8 Compared to the dull and fugitive vegetable dyes of the past, Scheele's Green was a revelation. Its brightness and stability made it an "instant success".8

Decades later, around 1814, a German company introduced an "improved" version known as Emerald Green or, more famously, Paris Green.1 Chemically, this was copper acetoarsenite,

3Cu(ASO2)2⋅Cu(CH3COO)2, and while it was even more durable, it was just as toxic.3 These pigments were products of a new age of industrial chemistry, a time when laboratory creations began to permeate daily life on a mass scale.13 From the very beginning, a pattern of prioritizing commerce over caution was established. Scheele himself was aware of the health risks associated with his creation but proceeded with its production nonetheless, unleashing a beautiful poison upon an unsuspecting world.10

The Green Epidemic: A Craze for Color

The new arsenic-based greens were not only brilliant, they were also relatively cheap to produce, a byproduct of the era's booming mining industry.16 This combination of affordability and vibrancy led to their explosive popularity. Soon, the color was everywhere. It adorned the walls of Buckingham Palace and was used in paints, bookbindings, and paper hangings.6 It colored artificial flowers, wax candles, children's toys, and was even used as a food dye for sweets and confections.6

Fashion, in particular, was seized by the craze. The most influential women's magazines of the day, such as Godey's Lady's Book, fueled the trend, featuring fashion plates with descriptions of ensembles in "Light green silk" or "black-green" fabrics.20 An 1854 issue of

Godey's described a "Camilla Mantilla" of "Light green silk, trimmed with Honiton lace," and a "Columbine" mantilla of "black-green or ruby-colored" silk.20 An 1855 issue went further, offering direct advice on color theory and beauty, noting that for women with fair, pink complexions, a "delicate green" was ideal to "maintain harmony of tone".21 With a circulation that reached 150,000 by 1860,

Godey's was a powerful engine of consumer desire, disseminating these new styles across the nation.22

The adoption of arsenical green was more than a simple fashion trend; it was a symptom of the new consumer culture forged by the Industrial Revolution. The mass production of goods created an aspirational middle class eager to adopt the markers of elite status.17 The affordability of arsenic green made a previously exclusive symbol—vibrant color—accessible to a much wider audience for the first time. This perfect storm of technological innovation, social aspiration, and new mass media created a "green epidemic," fundamentally changing how fashion was produced, marketed, and consumed, with deadly consequences.

Part II: The Price of Vanity: A Chronicle of Poisoning

The Makers' Agony: Casualties in the Factories

The first and most horrific price for this vibrant new color was paid by the workers who created it. The factories that produced the dyes, fabrics, and especially the delicate artificial flowers and leaves used to adorn dresses and headdresses, were staffed predominantly by young women and girls.13 Their working conditions were wretched, and their exposure to the arsenic dust was constant and direct.25

In his 1879 work Our Domestic Poisons, the reformer Henry Carr described the plight of these workers, particularly the girls employed to make artificial flowers. They suffered from "eruptions, painful cracking of the skin on their fingers and flexures of the arms".11 From one factory employing a hundred girls, he reported that only four appeared symptom-free, while twenty-six showed clear signs of chronic poisoning, and one had already died after months of suffering from ulcerations.11

The most harrowing and well-documented case is that of Matilda Scheurer, a 19-year-old artificial flower maker in London, whose death in 1861 became a public scandal.26 The inquest into her death provides a chilling, first-hand account of the poison's effects. Her mother, Mrs. Louisa Scheurer, testified that her daughter had been ill on and off for over a year with pains and sickness. In her final days, she was "seized with vomiting, and the refuse of the stomach was of a very greenish colour".29 She suffered terribly, convulsing every few minutes until she finally died.26

The surgeon who performed the post-mortem, Mr. James Thomas Paul, left no doubt as to the cause. He stated that the cause of death was "acute inflammation of the mucous membrane of the stomach, produced by the inhalation of the arsenite of copper".29 His examination revealed that her lungs and liver were "highly impregnated" with the poison, and that even the whites of her eyes and her fingernails had turned green.26 Tragically, he also noted that a sister of the deceased had died under similar circumstances.29

The testimony of Matilda's employer, M. Bergerond, revealed the institutionalized neglect that characterized the era's attitude toward worker safety.30 He admitted to employing 98 girls in his establishment and stated that for their protection, he had "suggested the wearing of masks, but it was objected to by them as producing excessive heat. They, however, wore muslin over their mouths".29 This tragically inadequate measure—a thin piece of muslin against a cloud of deadly dust—stood as the only barrier between these young women and a violent death. The jury's verdict, that Matilda had "died accidentally," effectively absolved the factory owner of responsibility, cementing a system where profit was held in far higher esteem than human life.29

The Wearers' Woe: Poisoned by Finery

While the wearers of these fashionable garments were afforded some protection by the many layers of underclothing common at the time—chemise, corset, petticoats—they were by no means immune to the poison they so proudly displayed.13 The fine arsenic-laced powder flaked off the fabrics, especially from the artificial leaves and flowers used as trim, leading to both topical irritation and systemic poisoning.9

Physicians and medical reformers began to document an alarming number of cases. Henry Carr's pamphlet is filled with such accounts: a person whose green gloves "made the hands swell," another whose stockings caused "serious irritation on her legs," and society ladies whose glamorous ball gowns led to "oozing sores, especially when combined with artificial flowers".11 The London surgeon Jabez Hogg related the case of a man whose fashionable green socks caused symptoms so severe he was "confined to home and couch," only recovering when he abandoned the toxic hosiery.11 Hogg also told of Californian miners who died from wearing boots lined with bright green flannel, a lady who suffered a painful skin disease from carrying a yellow purse (another color that could contain arsenic), and another with a skin eruption caused by the artificial flowers in her bonnet.11

The danger was not, in fact, limited to the color green. Arsenic was used as a component or mordant in other dyes, including some blues, yellows, and reds, though the brilliant green pigments were by far the most notorious and contained the highest concentrations.10 Stockings and gloves were particularly hazardous as they were worn directly against the skin.13 The threat was so well-recognized in medical circles that the

British Medical Journal published its famous, grimly humorous warning that a woman dressed in arsenic green "carries in her skirts poison enough to slay the whole of the admirers she may meet with in half a dozen ball-rooms".1 The poison had escaped the factory and entered the most intimate and celebrated spaces of Victorian life.

The Poisoned Domestic Sphere

The insidious threat of arsenic permeated the entire domestic environment. The same pigments used to dye dresses were used to print wallpaper, which became wildly popular in the mid-19th century.6 This introduced a new and terrifying vector for poisoning. In damp climates, like that of Great Britain, the wallpaper could become moldy. Certain fungi, such as

Scopulariopsis brevicaulis, were capable of metabolizing the arsenic-containing pigments and releasing poisonous arsine gas (AsH3) into the air.12

Journals of the period contained reports of "children becoming ill in bright green rooms" 6 and entire families, along with their pets, falling mysteriously ill, only to recover after the offending wallpaper was removed.9 One London surgeon, Dr. W, tragically lost his wife six months after papering a room with Scheele's green, her death attributed to the effects of arsenical poisoning.11 Perhaps the most famous suspected victim of this domestic poison is Napoleon Bonaparte. During his final exile on the damp island of St. Helena, he resided in a house where the rooms were decorated with his favorite color, green. It has long been theorized that the arsenical wallpaper in his humid home contributed to his death from stomach cancer in 1821. This theory is supported by later analyses of his hair, which revealed significantly high levels of arsenic.6

The pervasiveness of arsenic in the Victorian home created a diagnostic nightmare for 19th-century medicine. The symptoms of chronic, low-level arsenic poisoning—headache, fatigue, colic, diarrhea, skin blotches, and general malaise—are notoriously non-specific.25 They closely mimic other common and deadly illnesses of the era, such as cholera, dysentery, or diphtheria.32 It was not until the late 1860s that doctors began to firmly connect these widespread, mysterious maladies with the presence of green paper on the walls.9 Dr. Robert Brudenell Carter, a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, reported his belief that two of his own children had died as a result of arsenical wallpaper in their nursery.11 This suggests that for decades, countless individuals likely suffered and died from what we would now call chronic environmental poisoning, their deaths misattributed to other causes. The concept of a "sick building" or the danger of slow, cumulative toxic exposure was not yet part of the medical lexicon. The story of arsenic green is therefore not merely one of fashion, but one that marks the very beginnings of environmental toxicology and the immense challenge of identifying the slow, silent killers in our everyday surroundings.

Part III: Voices of Warning in a Willfully Deaf World

The slow-dawning realization of arsenic's pervasive danger did not occur in a cultural vacuum. It was one particularly lethal front in a much broader, multi-faceted war against the perceived harms of 19th-century women's fashion. While chemists and doctors sounded the alarm about specific poisons, other reformers were attacking the very structure and philosophy of contemporary dress. These parallel critiques—from medical professionals, social satirists, feminist activists, and religious leaders—converged on the same target: the dangerous, debilitating, and decadent clothing that defined the era.

Medical Alarms and Media Mockery

The turning point in public awareness can be traced to 1861 and 1862, catalyzed by the tragic death of Matilda Scheurer. Her story, and the inquest that followed, brought the plight of factory workers into the public eye. Shortly thereafter, in February 1862, the renowned chemist Dr. A.W. Hoffman published a letter in The Times titled "The Dance of Death".31 His investigation, notably funded by the Ladies' Sanitary Association, revealed the shocking extent of the danger. Hoffman concluded that an average woman's floral headdress contained enough arsenic to kill 20 people.32 A typical ball gown, he calculated, could shed as much as 60 grains of arsenic powder in a single evening—more than ten times a lethal dose for an adult.39

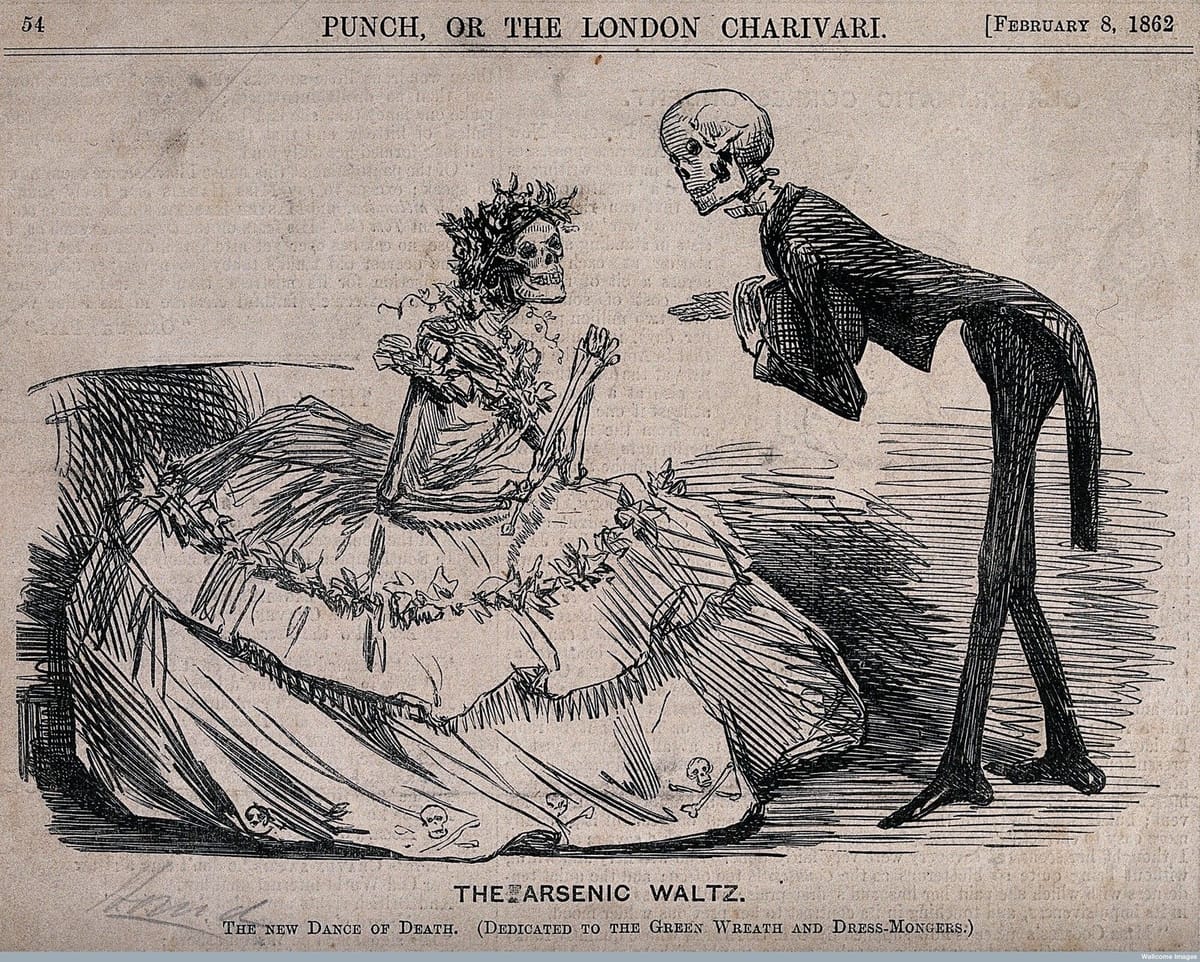

This exposé triggered a wave of media coverage. The British Medical Journal published its famous quip, declaring that the wearer of a green dress "may be called a killing creature" and that she "carries in her skirts poison enough to slay the whole of the admirers she may meet with in half a dozen ball-rooms".1 The popular satirical magazine

Punch delivered the most enduring critique with its iconic 1862 cartoon, "The Arsenic Waltz".16 The drawing depicted skeletons, clad in fashionable evening wear, dancing at a ball. The caption read: "The new Dance of Death. (Dedicated to the green wreath and dress-mongers.)".41

This combination of scientific warning and public mockery began to shift perceptions. The Ladies' Sanitary Association, an organization of primarily upper-class women, played a crucial role, transforming a concern for their own safety ("self-preservation") into a broader campaign for public and occupational health.25 Yet, the response was complicated. The satirical tone of the press, while raising awareness, may have also blunted the true horror of the situation, turning it into a "sensation" or a morbid joke rather than an urgent public health crisis.30 Despite the clear and present danger, the allure of the color was so strong that many women continued to wear it, and manufacturers continued to produce it.3

Parallel Critiques: The Broader Revolt Against Fashion's Tyranny

The specific fear of arsenic was amplified by a wider cultural critique of women's clothing, which was seen as oppressive from multiple perspectives: physically, politically, and morally.

The Dress Reform Movement: A Fight for Health and Freedom

Long before arsenic became a headline issue, a vocal group of reformers was already attacking the fundamental structure of women's fashion. Activists in the dress reform movement, many of whom were also leaders in the fight for women's suffrage, argued that contemporary clothing was a primary instrument of female oppression.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a leading figure in the movement, condemned the fashion of the day as a "badge of degradation".44 She railed against the "crippling, cribbing influence of her costume," which included heavy skirts that dragged on the ground and constricting corsets that damaged women's health.45 After adopting the "bloomer costume"—a shorter skirt worn over loose trousers—Stanton wrote ecstatically of her newfound liberation:

"What a sense of liberty I felt, in running up and down stairs with my hands free to carry whatsoever I would, to trip through the rain or snow with no skirts to hold or brush, ready at any moment to climb a hill-top to see the sun go down, or the moon rise... What an emancipation from little petty vexatious trammels and annoyances every hour of the day." 45

Her colleague, Amelia Bloomer, used her influential newspaper, The Lily, to champion the cause. Bloomer argued that clothing should be practical and healthful, stating, "The costume of women should be suited to their wants and necessities… conduce to her health, comfort, and usefulness".44 Physicians allied with the movement, such as Dr. William Alcott and the prominent educator Catharine Beecher, provided the medical rationale, warning that corsets weakened the lungs, displaced vital internal organs, and led to severe gynecological problems like uterine prolapse.44 For these reformers, the battle was not just against a single poison, but against a whole system of dress that they believed kept women physically weak, perpetually ill, and politically subjugated.

Religious Rebuke: A Stand Against Pride and Vanity

A second, powerful critique came from religious leaders who viewed the excesses of fashion as a sign of moral and spiritual decay. Their focus was less on physical freedom and more on the virtues of modesty, simplicity, and humility.

Ellen G. White, a founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, was a prominent voice for dress reform on both health and spiritual grounds. She directly condemned the physical harms of fashionable attire, writing in 1872:

"My sisters, there is need of a dress reform among us. There are many errors in the present style of female dress. It is injurious to health, for females to wear tight corsets, or whalebones, or to compress the waist. The health of the entire system depends on the healthy action of the respiratory organs." 49

Beyond the physical, White saw fashion as a moral trap. She argued that the obsession with "ruffles, flounces, puffs, tucks, and elaborate embroidery" was an expression of vanity that squandered time and money that should be devoted to God and service to the needy.50 She called for Christians to adopt a "simple style" in order to "rebuke the pride, vanity, and extravagance of worldly, pleasure-loving professors," creating a clear "distinction from that of the world" in their apparel.49

This sentiment was echoed in other religious communities. While direct sermons from Joseph Smith on this topic are not detailed in the available records, his successors in the leadership of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints vigorously carried on a tradition of warning against pride and worldliness in dress. In a "Call to the Women of the Church," President Joseph F. Smith lamented that "our women are prone to follow the demoralizing fashions of the world" and participate in "exhibitions of immodesty and of actual indecency in their attire".52 His predecessor, Brigham Young, had similarly cautioned against "indecent" fashions.52 At the core of these teachings was the scriptural concept of pride as the fundamental sin of "enmity toward God and enmity toward our fellowmen".55 Vain and extravagant dress was seen as a primary manifestation of this spiritual corruption. In a striking statement on the sacredness of religious clothing, Joseph F. Smith condemned those who would "mutilate" their holy garments "in order that we may follow the foolish vain and (permit me to say) indecent practices of the world".56 For these religious reformers, the problem with fashion was not merely that it was unhealthy, but that it was unholy.

A Literary Symbol: The Exploitation of Jemima Jones

While the user's query names "Jemima Jones" as a reformer, historical research reveals she was not a real person but a powerful fictional creation. Jemima is a central character in Mary Wollstonecraft's final, unfinished novel, The Wrongs of Woman (1798).57 In the novel, Jemima represents the ultimate victim of an unjust patriarchal society. Born illegitimate, she is exploited as a domestic servant, a worker in a workhouse, and a prostitute. She gives voice to the voiceless, describing her own life as that of "a slave, a bastard, a common property".57

Though Wollstonecraft wrote before the advent of arsenic green, her character of Jemima serves as a potent literary symbol for the very class of women who would become the primary casualties of its production. Jemima's story of being relentlessly "exploited as a worker" 57 is the fictional parallel to the real-life tragedy of Matilda Scheurer and the thousands of other anonymous factory girls. Her narrative powerfully illustrates the social and economic "wrongs" that made working-class women vulnerable to the dangerous trades of the 19th century. While she never penned a warning against poison dyes, her story stands as a timeless indictment of a system that commodified and consumed the lives of poor women for the sake of luxury and fashion.

Part IV: The End of the Green Reign and Its Museum Afterlife

The Dawn of a Safer Rainbow: Aniline Dyes

The reign of arsenical green was ultimately brought to an end not by legislation or moral suasion alone, but by the same force that had created it: chemical innovation. In 1856, an 18-year-old English chemist named William Henry Perkin was attempting to synthesize quinine, a treatment for malaria. His experiment failed, but in the process, he accidentally created a crude black substance that, when purified, yielded an intense purple dye.4 He had discovered mauveine, the world's first synthetic aniline dye, derived from the industrial waste product of coal tar.4

Perkin's discovery was revolutionary. It launched the synthetic dye industry, which quickly developed a vast palette of brilliant, colorfast, and inexpensive colors.4 By the early 1860s, these new aniline dyes, including new and safer greens, had "all but replaced vegetable dyes for clothes".25 They offered all the vibrancy of the arsenic pigments without the acute toxicity, rendering the dangerous compounds largely obsolete for use in fashion.7 This development illustrates a crucial historical lesson: while public outcry and media campaigns can raise awareness, a hazardous technology is often only truly abandoned when a superior, safer, and equally profitable alternative becomes widely available.

Fading from Fashion: The Decline of a Killer Trend

By the late 19th century, the confluence of factors was overwhelming. The sustained pressure from medical professionals, the shocking media exposés, the mockery of satirists, and, crucially, the availability of the new aniline dyes finally sealed the fate of arsenical green in the world of fashion.12 Public awareness had reached a point where manufacturers began to see a commercial advantage in safety, and advertisements for "arsenic-free" products started to appear.18

The decline was gradual, a testament to what one historian called the "glacial pace of public concern".30 But by the 1890s, the last brands of wallpaper using the pigment had ceased production, and the once-fashionable color had fallen into disfavor.12 While Paris Green would continue to be used as an insecticide and pesticide for decades, eventually being banned in the 1960s, its career as a fashion statement was over.6 The green epidemic had finally run its course.

A Toxic Legacy: Conservation in the Modern Museum

The story of these deadly dresses, however, does not conclude in the 19th century. It continues today in the quiet, climate-controlled storage facilities of museums around the world. Institutions like The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Maryland Center for History and Culture hold examples of these garments in their collections, beautiful artifacts that remain actively hazardous.10 One museum professional noted that some Victorian dresses are "still emitting arsenic exposure to this day".1

This toxic legacy has created a unique and challenging field within textile conservation. The arsenic compounds, primarily copper arsenite and copper acetoarsenite, do not simply degrade into harmlessness over time. As the silk and cotton fibers of the historic garments become brittle with age, they can shed microscopic, arsenic-laden dust particles.35 This dust poses a direct health risk—through inhalation or ingestion—to the curators, conservators, and researchers who handle them.27

Consequently, these artifacts are treated as hazardous materials. Modern conservation protocols demand that they be handled with extreme care. Staff must wear protective equipment, including vinyl or latex gloves and personally fitted respirators with High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) cartridges, to prevent exposure.66 The objects themselves are segregated from other textiles and stored in specially marked bags, enclosures, or hazardous storage cabinets to prevent cross-contamination.66

In recent years, museum science has adopted advanced technologies to manage this threat. Conservators now use tools like portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) spectroscopy to analyze the elemental composition of textiles.68 This non-invasive technique allows them to test for the presence of arsenic, lead, and other heavy metals without damaging the fragile, historic fabric. This data is critical for conducting risk assessments, surveying entire collections, and developing safe handling protocols or even potential decontamination procedures, such as highly invasive wet cleaning methods, for these beautiful but deadly objects.68

These historical artifacts thus have a dynamic, ongoing "life" as hazardous materials, creating a fascinating intersection of history, chemistry, and 21st-century occupational safety. The dress that was once "dressed to kill" in a Victorian ballroom remains, in a very real and measurable way, a dangerous object today.

Conclusion: Lessons from a Poisoned Past

The story of arsenic green is a vivid and tragic chapter in the history of fashion and technology. It stands as a stark reminder of the complex and often fraught relationship between aesthetic desire, commercial enterprise, and public health. The quest for a perfect, vibrant green led to a chemical innovation that enchanted a generation, but the unregulated rush to market a popular product unleashed a slow-motion public health crisis that claimed an untold number of lives, from the young factory girls who died in agony to the wealthy women and children poisoned in their own homes.

The voices of warning were many, but they came from different corners of society and spoke different languages of concern. Doctors and chemists pointed to the physical evidence of poison, citing mortality statistics and chemical analyses. Social reformers like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer saw the broader tyranny of fashion as a tool of women's physical and political subjugation. Religious leaders like Ellen G. White decried the moral poison of pride and vanity that such extravagant fashions represented. It was only when these disparate critiques combined with the arrival of a safer technological alternative—aniline dyes—that the deadly trend finally abated.

Today, the tale of Scheele's Green resonates with modern anxieties about hazardous materials in our own consumer goods, from chemicals in fast fashion to additives in our food. It underscores the enduring tension between industry's pursuit of profit and society's need for protection. The ultimate legacy of this killer color can be found in museum collections, where the surviving green dresses are preserved. They are artifacts of exquisite beauty, testaments to a bygone era's style and craft. But they are also potent symbols of a hidden history of suffering and tangible, toxic reminders of the dangers that can lurk just beneath a beautiful surface. Even now, carefully stored and handled with gloved hands, they remain dressed to kill.

Works cited

- The Price of Fashion - Arsenic Green - Tees Valley Museums, accessed June 19, 2025, https://teesvalleymuseums.org/blog/post/the-price-of-fashion/

- A Dark History of Arsenic Greens - Under The Moonlight, accessed June 19, 2025, https://underthemoonlight.ca/2018/03/17/a-dark-history-of-arsenic-greens/

- An Update on Arsenic Green: When the World was Dying for Color, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.mdhistory.org/an-update-on-arsenic-green-when-the-world-was-dying-for-color/

- Victorian Fabric Dyes | …What Someone Wrote Down - A. Whitney Brown, accessed June 19, 2025, https://whatsomeonewrotedown.wordpress.com/2016/02/22/victorian-fabric-dyes/

- From Coal Tar to Couture: The Discovery of Aniline Dyes and The Effect Upon Fashion, accessed June 19, 2025, https://blogs.duanemorris.com/fashionretailbrandedconsumergoods/2023/02/09/from-coal-tar-to-couture-the-discovery-of-aniline-dyes-and-the-effect-upon-fashion/

- The History of the Color Green: How the Poisonous Pigment Came to Be - My Modern Met, accessed June 19, 2025, https://mymodernmet.com/history-of-the-color-green/

- Respect the chemistry - The Fine Art Collective, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.the-fine-art-collective.com/en/2019/07/10/respect-the-chemistry/

- Scheele's_Green - chemeurope.com, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.chemeurope.com/en/encyclopedia/Scheele%27s_Green.html

- Death on the doorstep: Arsenic in Victorian wallpaper - Saint Louis Art Museum, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.slam.org/blog/arsenic-in-victorian-wallpaper/

- The Dyes of Death - Maryland Center for History and Culture, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.mdhistory.org/the-dyes-of-death/

- Arsenic: a domestic poison - Royal College of Surgeons, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/arsenic-a-domestic-poison/

- Scheele's green - Wikipedia, accessed June 19, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scheele%27s_green

- Tag: paris emerald scheele's green - The Pragmatic Costumer - WordPress.com, accessed June 19, 2025, https://thepragmaticcostumer.wordpress.com/tag/paris-emerald-scheeles-green/

- Drop Dead Gorgeous: A TL;DR Tale of Arsenic in Victorian Life - The Pragmatic Costumer, accessed June 19, 2025, https://thepragmaticcostumer.wordpress.com/2014/06/11/drop-dead-gorgeous-a-tldr-tale-of-arsenic-in-victorian-life/

- A Rainbow Palate: How Chemical Dyes Changed the West's Relationship with Food 9780226727196 - DOKUMEN.PUB, accessed June 19, 2025, https://dokumen.pub/a-rainbow-palate-how-chemical-dyes-changed-the-wests-relationship-with-food-9780226727196.html

- Arsenic and Old Lace - Deborah Challinor - annotated., accessed June 19, 2025, http://deborahchallinor.blogspot.com/2012/12/arsenic-and-old-lace.html

- When the Walls Were Painted With Poison - WebMD, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/features/scheeles-green?src=rss_public

- The dark side of green, i.e. arsenic unveiled… - PCC Group Product Portal, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.products.pcc.eu/en/blog/the-dark-side-of-green-i-e-arsenic-unveiled/

- A cartoon appearing in the popular humour magazine Punch, or the London... | Download Scientific Diagram - ResearchGate, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/A-cartoon-appearing-in-the-popular-humour-magazine-Punch-or-the-London-Charivari_fig1_390828963

- The Project Gutenberg eBook of Godey's Lady's Book; Philadelphia, April, 1854., accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/58494.html.images

- Choice of Colors in Dress; Or, How a Lady May Become Good Looking (Godey's Lady's Book, 1855) : r/DressForYourBody - Reddit, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/DressForYourBody/comments/z5l6u9/choice_of_colors_in_dress_or_how_a_lady_may/

- Special Collections Highlight: Godey's Lady's Book, Sarah Josepha Hale, and American Culture | The New York Society Library, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.nysoclib.org/blog/special-collections-highlight-godeys-ladys-book-sarah-josepha-hale-and-american-culture

- Godey's Lady's Book - Wikipedia, accessed June 19, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Godey%27s_Lady%27s_Book

- Nineteenth-Century European Textile Production - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/nineteenth-century-european-textile-production

- A Kind of Dread: Arsenic and Occupational Health Introduction During the nineteenth century arsenic entered the public conscious - Brill, accessed June 19, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004333482/BP000006.pdf

- Work-related health — then and now | Croner-i, accessed June 19, 2025, https://app.croneri.co.uk/feature-articles/work-related-health-then-and-now

- Toxins in the Collection: Museum Awareness and Protection - Digital Commons at Buffalo State, accessed June 19, 2025, https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=museumstudies_theses

- Toxic trends | Wellcome Collection, accessed June 19, 2025, https://wellcomecollection.org/stories/toxic-trends

- Matilda Scheurer - Poisoned By Artificial Flowers 1861. - Jack The Ripper Tour, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.jack-the-ripper-tour.com/generalnews/poisoned-by-flowers/

- James C. Whorton, The Arsenic Century - Cambridge University Press & Assessment, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/60731B6F0E30EE9A7177AF17888A151D/S0025727300005913a.pdf/james-c-whorton-the-arsenic-century-how-victorian-britain-was-poisoned-at-home-work-and-play-oxford-oxford-university-press-2010-pp-xxii-412-pound1699-hardback-isbn-978-0-19-957470-4.pdf

- Deadly Frocks and Other Tales of Murder Clothes - Uncanny Magazine, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.uncannymagazine.com/article/deadly-frocks-and-other-tales-of-murder-clothes/

- Arsenical by Design - save the moulages, accessed June 19, 2025, https://savethemoulages.org/2017/09/10/arsenical-by-design/

- Colour story: Emerald Green - Winsor & Newton, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.winsornewton.com/blogs/articles/emerald-green

- So Toxic: Everyday Dangers of the 19th Century, accessed June 19, 2025, https://customshousemuseum.org/news/so-toxic-everyday-dangers-of-the-19th-century/

- It's Not Easy Being Green | Guardians of Memory - Library of Congress Blogs, accessed June 19, 2025, https://blogs.loc.gov/preservation/2024/03/being-green/

- Scheele's green was the most fashionable colour for the Victorian elite. Unfortunately the dye combined copper and arsenic and resulted in skin cancer, killing hundreds of textile workers. Did someone say those dresses are to die for? : r/HistoricalRomance - Reddit, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/HistoricalRomance/comments/1be5rv1/scheeles_green_was_the_most_fashionable_colour/

- Reframing the Victorians: 'The Age of Arsenic', accessed June 19, 2025, http://reframingthevictorians.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-age-of-arsenic.html

- Arsenic Poisoning: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment - Patient.info, accessed June 19, 2025, https://patient.info/doctor/arsenic-poisoning

- Victorian Era Fashion: Green Gowns To Die For! - Racing Nellie Bly, accessed June 19, 2025, https://racingnelliebly.com/weirdscience/victorian-era-fashion-green-gowns/

- Many old books contain toxic chemicals - University of Hull, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.hull.ac.uk/work-with-us/more/media-centre/news/2024/many-old-books-contain-toxic-chemicals

- John Leech Cartoons from Punch magazine, accessed June 19, 2025, https://magazine.punch.co.uk/image/I0000av.zFaAuIAc

- (PDF) Pages of Poison: Identifying 19th Century Arsenical Green Books at Queen's University - ResearchGate, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390828963_Pages_of_Poison_Identifying_19th_Century_Arsenical_Green_Books_at_Queen's_University

- Book Reviews: The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play - PMC, accessed June 19, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3066680/

- Dress Reform – First Wave Feminisms - UW Sites - University of Washington, accessed June 19, 2025, https://sites.uw.edu/twomn347/2019/12/13/dress-reform/

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton and fashion | Blogging Einstein - WordPress.com, accessed June 19, 2025, https://bloggingeinstein.wordpress.com/2013/09/21/elizabeth-cady-stanton-and-fashion/

- The Bloomer Movement - Susan Higginbotham, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.susanhigginbotham.com/posts/the-bloomer-movement/

- How Did We Get Here? A Letter to the American Fashion Industry - Reformation 21, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.reformation21.org/blog/how-did-we-get-here-a-letter-to-the-american-fashion-industry

- Victorian dress reform - Wikipedia, accessed June 19, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victorian_dress_reform

- The Health Reformer - Ellen G. White Writings, accessed June 19, 2025, https://m.egwwritings.org/en/book/504.482

- The Health Reformer — Ellen G. White Writings, accessed June 19, 2025, https://m.egwwritings.org/en/book/504.950

- A Distinction in Dress, September 22 - Ellen G. White Estate: Daily Devotional - Our High Calling, accessed June 19, 2025, https://whiteestate.org/devotional/ohc/09_22/

- "A Style of Our Own": Mormon Women and Modesty - Dialogue Journal, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.dialoguejournal.com/articles/a-style-of-our-own-mormon-women-and-modesty/

- Modesty-A Call to the Women of the Church, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.reliefsocietywomen.com/blog/2008/06/05/modesty-a-call-to-the-women-of-the-church/

- Reverencing Womanhood - BYU-Idaho, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.byui.edu/speeches/reverencing-womanhood

- Beware of Pride - The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/eternal-marriage-student-manual/pride/beware-of-pride?lang=eng

- Joseph F. Smith describes garments as unchanged. - B. H. Roberts Foundation, accessed June 19, 2025, https://bhroberts.org/records/09wgH3-kO8Oec/joseph_f_smith_describes_garments_as_unchanged

- Jemima's wrongs: Reading the female body in Mary Wollstonecraft's prostitute biography - Revistas UM - Universidad de Murcia, accessed June 19, 2025, https://revistas.um.es/ijes/article/download/341191/266681/1293191

- Colleen Fenno, Testimony, Trauma, and a Space for Victims: Mary Wollstonecraft's "Maria: Or the Wrongs of Woman" • Issue 8.2, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.ncgsjournal.com/issue82/fenno.html

- Aniline, accessed June 19, 2025, https://trcleiden.nl/trc-needles/materials/dyes/aniline

- aniline dyes | Fashion History Timeline, accessed June 19, 2025, https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/aniline-dyes/

- Aniline Dyes - Pysanky.info, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.pysanky.info/Chemical_Dyes/History.html

- Making Color - Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, accessed June 19, 2025, https://library.si.edu/exhibition/color-in-a-new-light/making

- Fashion Archives Archives – Page 7 of 8 - Maryland Center for History and Culture, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.mdhistory.org/category/fashion-archives/page/7/

- Barbara P. Katz Fashion Archives - Maryland Center for History and Culture, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.mdhistory.org/collections/fashion-archives/

- Fashion Archives - Maryland Center for History and Culture, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.mdhistory.org/category/fashion-archives/

- Conserve O Gram Volume 2 Issue 10: Hazardous Materials In Your Collection, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/museums/upload/02-10_508.pdf

- Textile Conservation - Mainly Museums, accessed June 19, 2025, https://mainlymuseums.com/post/839/textile-conservation/

- Coping with arsenic-based pesticides on textile collections - Resources | Conservation Online, accessed June 19, 2025, http://resources.culturalheritage.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2015/03/osg021-08.pdf

- Full article: Toxic Tales: Arsenic's Legacy in Nineteenth-century Green Book Bindings at Northwestern University Libraries - Taylor & Francis Online: Peer-reviewed Journals, accessed June 19, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00393630.2025.2460403