Economic Transformation and the Fires of Revival

A Land Transformed and Inflamed by Faith

By the 1820s and 1830s, the once-remote frontier of western New York had been utterly transformed by economic change. New networks of canals, burgeoning towns, and thriving markets upended traditional ways of life. Amid the Erie Canal’s completion in 1825 and the ensuing market revolution, communities from Albany to Buffalo experienced unprecedented growth and social flux. This chapter examines how that economic transformation helped ignite the “fires of revival” in the so-called Burned-Over District – a region so alight with religious fervor that, as one revivalist quipped, there was no “fuel” (unconverted souls) left to burn.¹ Economic forces did not merely coincide with the Second Great Awakening’s flare-up in this area; they actively shaped it. Prosperity and disruption went hand in hand: new wealth, social mobility, urbanization, and dislocation created both the impetus and the audience for intense religious revivals. In turn, these revivals offered meaning, community, and moral order amid the whirlwind of change. This chapter explores that dynamic interplay, analyzing how canals and markets paved the way for camp meetings and conversions. It will spotlight key locales – Rochester, Palmyra, and other canal towns – to illustrate how economic change fanned the flames of religious enthusiasm. Direct voices from the era, from preachers to converts, will appear alongside modern scholarly insights. By the end, we will see that the Burned-Over District’s spiritual wildfire was deeply rooted in the soil of economic transformation, setting the stage for further explorations of social mobility and the quest for meaning in the next chapter.

The Erie Canal: Waterway of Wealth and Awakening

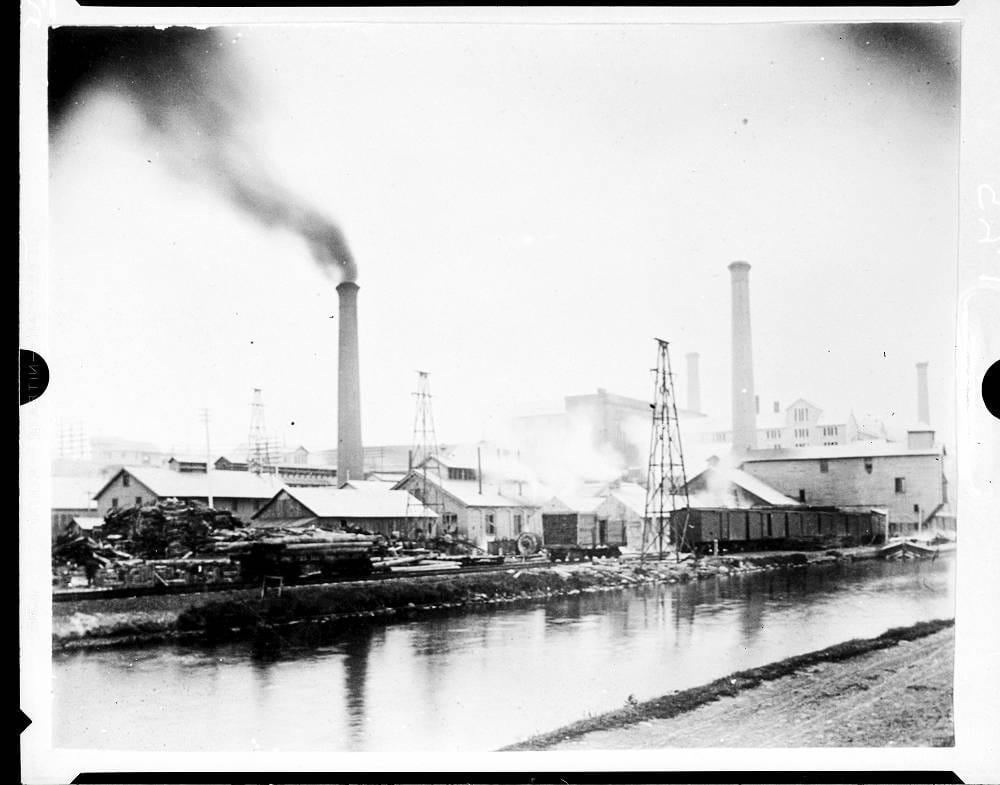

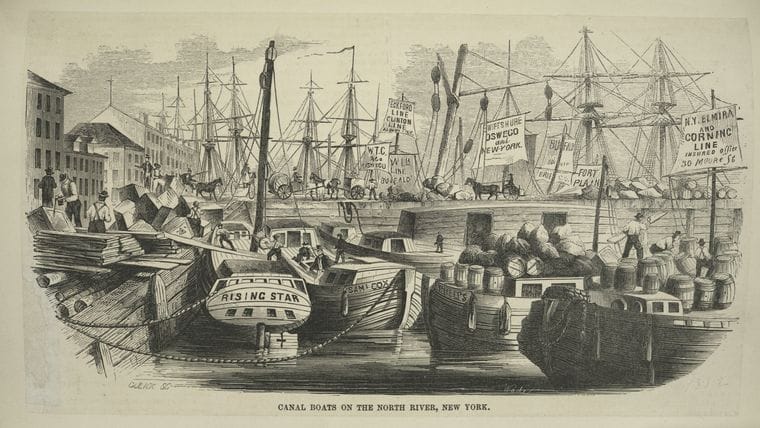

When Governor DeWitt Clinton’s grand “Erie Canal” opened in 1825, it was more than an engineering marvel – it was an economic tsunami that swept through upstate New York, carrying people, goods, and even ideas. The canal linked the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, cutting through the heart of the Burned-Over District. Its impact on the region’s economy was immediate and immense. Towns like Utica, Syracuse, Palmyra, and Rochester sprang up or expanded rapidly along the canal’s path, turning frontier settlements into commercial hubs almost overnight. In 1816, the village of Rochester barely existed; a decade later, after the canal’s arrival, Rochester was America’s first true “boomtown,” its population exploding from just 331 in 1815 to over 9,000 by 1830.² The once-isolated Genesee Valley became, in one traveler’s words, “a bustling entrepôt of flour mills, packet boats, and entrepreneurial fervor.” The Erie Canal hauled wheat, lumber, and manufactured wares – but it also carried itinerant preachers, evangelists’ tracts, and news of the latest revival. As one historian aptly puts it, the canal corridor became a “psychic highway” as much as a physical one, shuttling new religious movements as swiftly as merchandise.³

The economic boom brought by the canal created an atmosphere ripe for social and spiritual ferment. Prosperity was palpable – farmers found distant markets for their crops, merchants grew rich in canal towns, and young laborers flocked to construction and shipping jobs with hopes of advancement. Yet prosperity was uneven and always in flux. The very mobility and growth that enriched some unsettled others. Migrants poured in from New England and abroad, uprooted from old communities and traditions. Canal construction crews – including many Irish immigrants – introduced a transient, rough-and-tumble element to canal towns, sometimes unnerving the settled residents with their drinking and carousing. Economic opportunity came with social dislocation: families moved frequently in search of land or work, and class divisions sharpened between those who capitalized on the new economy and those left struggling. In short, the canal made western New York cosmopolitan and fluid – a patchwork of newcomers, youthful populations, and jostling social classes. According to the Erie Canal’s heritage historians, the canal corridor’s general prosperity and **mix of people “from all over the Atlantic world” created a climate where social innovation and questioning of the established order could flourish.**⁴ Traditional authorities, whether the old Eastern churches or local elites, held less sway in this restless environment. A kind of spiritual vacuum – or opportunity – opened up, into which fiery new religious enthusiasm flowed.

It is no coincidence that so many influential revival movements began in canal towns. Evangelist Charles G. Finney observed that wherever the canal went, “a divine influence seemed to pervade the community”, preparing souls for revival.⁵ Indeed, religious revivalism swept the Erie Canal corridor with such intensity in the 1820s and ’30s that the region itself gained a famous moniker: the “Burned-Over District.”⁶ New sects and prophets seemed to spring up with the same explosive energy that drove the canal’s commerce. The Latter-day Saints (Mormons) under Joseph Smith, the Millerites expecting Christ’s imminent return, the Seventh-day Adventists and other offshoots of that millennial fervor – all emerged from communities along the canal. Perfectionist utopias like the Oneida Community likewise took root near the canal’s route, their founders finding followers among those disenchanted with conventional society.⁷ While waterways themselves did not cause revivals, they enabled the swift diffusion of revivalist preachers and ideas. The canal made it feasible for an evangelist to hold a meeting in Syracuse one week and in Lockport the next, much as railroads and the telegraph would aid later movements. Finney himself traveled by canal boat to reach some of his most important revival fields. When he received an invitation in 1830 to preach in Rochester – a city at the canal’s western end – Finney literally “floated” into the revival on the new economic tide. As he later recounted, “We went on board a canal boat; and in due time another boat, bound for Rochester, came along, and we embarked… On board that boat I found a prominent elder… who was going to Rochester. We had much conversation on the way. He seemed to be full of the Spirit of prayer… and before we arrived he said, ‘Brother Finney,* the Lord has kept me awake all night, praying for Rochester. I trust He is about to pour out His Spirit there.**’”*⁸ This sense of expectancy – that God was about to do great things in a boomtown – was telling. The new economic infrastructure quite literally ferried revivalism into the heart of the Burned-Over District, and the hopes of the devout rode alongside the crates of flour and barrels of whiskey on the canal’s boats.

Boomtowns and Holy Fire: Rochester as a Case Study

No place embodied the marriage of economic upheaval and religious fervor better than Rochester, New York. In the late 1820s, Rochester was a city barely out of its infancy – a “raw and boisterous” boomtown sprung up at the falls of the Genesee River, where the new canal carried in commerce from afar. Its growth was staggering: “I can hardly recognize the place,” remarked one astonished visitor in 1829, “where ten years ago stood a mere mill and a few huts, now rises a bustling city of brick warehouses and crowded streets.” The population was young (over three-quarters of Rochester’s residents were under 30) and predominately composed of recent migrants – ambitious Yankee farmboys-turned-clerks, Irish canal laborers, itinerant craftsmen, and entrepreneurs of every stripe.⁹ Wealth accumulated quickly for some: Rochester’s flour mills – powered by the river and supplied by rich western farms via the canal – made it the nation’s leading flour producer, minting new millers and merchants as affluent citizens. But such breakneck expansion came with chaos. Saloons and taverns multiplied on every corner to slake the thirst of canal boatmen and mill workers; by one count, in 1827 there were over 100 establishments selling liquor for a population of just 7,500.¹⁰ Disorderly drunkenness, gambling, and crime earned parts of the town nicknames like “the Devil’s half-acre,” and church leaders lamented that sin had staked an early claim on the boomtown. One local minister decried Rochester as “the seat of Satan” in those years, noting that traditional churches were nearly empty while vice and irreligion thrived.¹¹ To many upstanding citizens – especially the emerging middle class of shopkeepers and skilled tradesmen – it seemed the city’s moral compass was spinning out of control under the pressures of rapid urbanization.

Yet beneath the seeming disorder, a spiritual tinder was drying out, ready to ignite. The same energetic young populace that indulged in Rochester’s rough amusements also hungered for community and purpose. Many of Rochester’s recent arrivals had come from religious backgrounds in New England and brought with them expectations of church life – even if initially those institutions lagged behind the growth. In the late 1820s, concerned local Christians formed prayer groups and revival committees, sensing that God might be preparing a change. The stage was set for a religious awakening that would match Rochester’s economic boom in intensity. In 1830, when the Reverend Charles Grandison Finney accepted an invitation to hold revival meetings in Rochester, these latent forces met their catalyst. Finney was a new breed of revivalist – a former lawyer turned fiery itinerant preacher, brimming with innovative evangelical tactics and an uncompromising message that called sinners to choose conversion now. He arrived in Rochester in the autumn of 1830 via the canal (as noted earlier), already feeling that “a great work” was imminent. His reputation from earlier revivals in small towns preceded him, and curiosity was high. What followed in Rochester during the fall and winter of 1830–31 would become legend in American religious history.

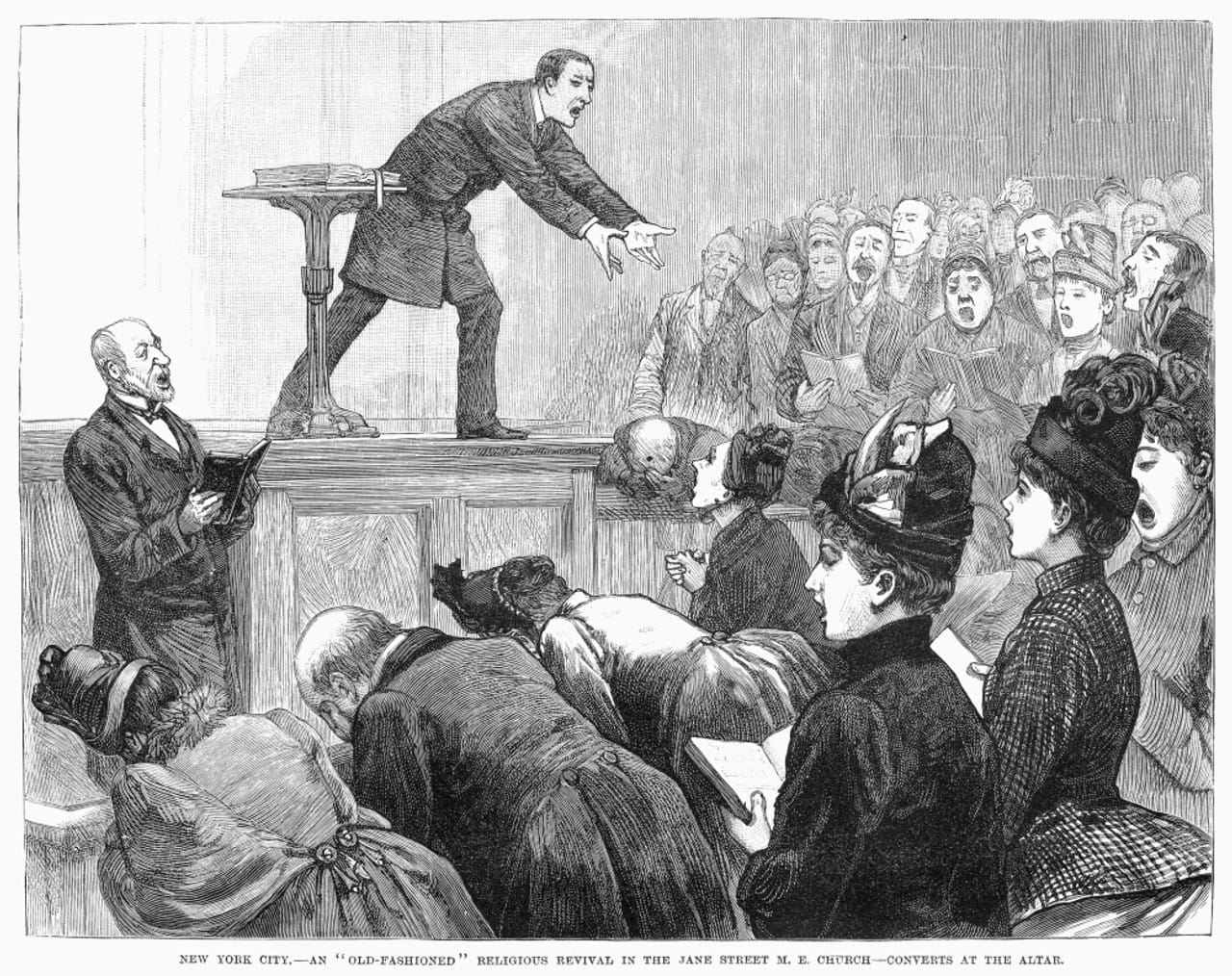

Finney’s meetings began modestly in the Third Presbyterian Church, but soon crowds overflowed the venues. He held nightly preaching services and midday prayer gatherings; stores closed early to allow people to attend. By contemporary accounts, all classes of society were drawn under the revival’s influence. Prominent businessmen and lawyers bowed alongside mechanics, boatmen, and housewives at the “anxious bench” (Finney’s pointed innovation for those under conviction). The message was simple yet electrifying: salvation was within immediate reach of even the worst sinner, and the Holy Spirit was visibly moving in Rochester. An eye-witness, the Rev. Asa Mahan, described scenes of weeping and rejoicing, noting that hardened men who had scoffed at religion “were suddenly overwhelmed with a sense of their guilt and danger, and in the streets, in their shops, or by their firesides, would fall on their knees and cry for mercy.”¹² The revival fire spread from congregation to congregation – across denominational lines. Methodist, Baptist, and Congregational churches in the city all reported surges of new members. The local newspaper printed reports of hundreds of conversions within weeks. Finney organized volunteers to visit homes and invite people to meetings; women held prayer circles and testified in public gatherings (a controversial break from decorum that Finney encouraged). By the spring of 1831, it was estimated that as many as 1,500 people – out of a city of 10,000 – had experienced conversion and joined Rochester’s various churches.¹³ The spiritual turnaround was so dramatic that Rochester’s revival of 1830–31 became a national sensation. Reform movements followed in its wake: the temperance campaign in Rochester gained huge momentum as newly converted citizens pledged to renounce alcohol. In the months after the revival, observers noted that many taverns closed for lack of business, and crimes of drunkenness and disorder visibly declined.¹⁴ What had been “Satan’s” stronghold seemed conquered by evangelical fervor.

The broader significance of Rochester’s revival was not lost on leading figures of the day. Celebrated preacher Lyman Beecher (a staunch defender of earlier Calvinist orthodoxy) begrudgingly acknowledged the power of Finney’s work, reportedly exclaiming that **“the work in Rochester was the greatest work of God, and the greatest revival of religion, that the world has ever seen in so short a time.”**¹⁵ News of the conversion wave spread through religious periodicals and word of mouth along the canal and beyond. Revival fires, once kindled in Rochester, leapt to other communities – a pattern so common in this era that it fuels the “fire” metaphor of the Burned-Over District. Finney himself reflected that the Rochester experience catalyzed revivals in scores of towns: *“This was the starting point of a general revival, the influence of which was felt in nearly all the regions round about. The flame spread…”*¹⁶ Indeed, in the early 1830s, similar scenes unfolded in Utica, Syracuse, Auburn, and smaller villages throughout western New York, often aided by converts from Rochester carrying the torch of testimony. The economic networks of the region became conduits for spiritual spread: converted merchants traveled on business, speaking of the revival; printed sermons and hymnals were distributed via canal boats and stagecoach; even the newly built rail lines (by the late 1830s) helped disseminate revival news. In Rochester’s wake, revivalism gained a new respectability among the middle class as well – it was seen not as backwoods emotionalism, but as a force for social stability and moral order in boomtown America. Historians have since dubbed the Rochester revival “a shopkeepers’ Pentecost,” highlighting that many converts were from the ranks of the city’s shop owners and skilled artisans – those poised between old aristocracy and the working poor, eager for a moral community that supported hard work and sobriety.¹⁷ For these folk, evangelical religion provided both genuine spiritual solace and a reinforcement of values (temperance, thrift, self-discipline) that suited the new market economy. At the same time, poorer laborers also joined the churches in significant numbers, sometimes finding in the revival a newfound sense of dignity and hope that their tumultuous economic life did not supply. Rochester thus exemplified how economic transformation and revivalism intertwined: the city’s growth created the conditions for religious upheaval, and the revival in turn sought to guide the city’s development along more virtuous lines.

New Wealth, New Anxieties, and the Turn to Faith

Across the Burned-Over District, the patterns visible in Rochester repeated in varied forms. Economic change brought both opportunity and anxiety, driving people of different classes toward religious solutions. For the newly prosperous, religious revivals often validated their success and gave it a higher purpose; for the struggling or uprooted, revivals offered comfort, community, and even the promise of miraculous redress (if not in this world, then the next). Historians of the Second Great Awakening in this region emphasize that revivalism thrived especially in places undergoing rapid socioeconomic shifts.¹⁸ Unlike the First Great Awakening of the 18th century – which spread largely through long-settled towns – the Second Great Awakening in upstate New York found its most ardent reception in communities on the make.

One facet was the role of the emerging middle class. As commerce flourished in canal towns, a class of merchants, professionals, and master craftsmen arose who were not part of the old gentry but aspired to respectability and order. For these men and women, evangelical religion often became a badge of middle-class identity – a way to distinguish oneself from the unruly, unchurched masses and to forge networks of trust in a volatile economy. Church membership could foster business contacts and mutual aid; participation in Bible societies or missionary associations honed leadership skills and public reputation.¹⁹ Perhaps more deeply, the revivalist message of personal moral reform resonated with the ethic of self-discipline needed in an entrepreneur. Conversion narratives that spoke of abandoning laziness and drink for industry and uprightness mirrored the success stories of self-made businessmen. It is telling that many key supporters of revivals were local businessmen who donated funds, organized meetings, and promoted Sabbath observance and temperance. In Utica, a canal-connected industrial town, revival fervor in the 1820s was championed by prominent citizens who saw religion as a means to “clean up” the city and its workforce.²⁰ The confluence of religious and economic motives was not cynical but rather reflected an overlap of values: revival Christianity preached honesty, sobriety, thrift, and charity – virtues that also undergirded a stable market society.

Meanwhile, the working classes and rural folk faced their own upheavals. Farm families who had sold lands in older states and moved to the new frontier of western New York often encountered hardships – debt, uncertain markets, isolation from kin – that made them receptive to the emotional support of revivals. The market revolution could be harsh: a sudden drop in wheat prices or the Panic of 1819 (an economic crash) ruined many aspiring farmers and merchants. Such reversals led people to seek refuge in faith, some interpreting economic misfortune as a spur to get right with God. In revival meetings, the poor and rich knelt side by side, equal in their dependence on divine grace. Indeed, evangelical preachers deliberately emphasized the spiritual equality of all persons – a message of comfort to those of low status. As one Baptist minister in western New York declared at an 1834 camp meeting, “The Lord is no respecter of persons; the wealthy merchant must repent just like the humble laborer, and the farmwife in her cabin may taste the same glory as the lady in her mansion.” Such rhetoric provided a measure of psychic leveling in a society where material leveling was elusive. It also subtly challenged the nascent class structure: revivalism, by focusing on the worth of the soul over worldly wealth, could critique greed and remind the prosperous of their duties. For example, revival converts were often pressed to give to the poor, fund missions, or otherwise use their wealth charitably, partially tempering the starkness of economic competition with Christian compassion.

Urban workers in canal cities, who often endured unstable employment and harsh living conditions, found in some revival movements a promise of deliverance not just spiritually but socially. The push for temperance, which was tightly linked with revival religion in this era, was embraced by many laborers’ families who had suffered from alcoholism’s toll. When a father or husband was converted at a revival and swore off liquor, his family’s economic fortunes often visibly improved – more wages went to bread rather than the tavern. Thus, the revival could directly better material life for the lower classes, and this tangible benefit did not go unnoticed. A Rochester mechanic’s wife testified in 1832 that *“God has not only saved my husband’s soul, but He has saved our household from poverty. Since the revival reached him, he spends his evenings at home and our children have shoes and schooling.”*²¹ Such stories circulated widely, encouraging others to see conversion as a path to a better life here and now, as well as eternal life. Revivalism in the Burned-Over District, therefore, bridged sacred and secular aspirations: it was about saving souls, certainly, but it was also entwined with attempts to remake society (or one’s own condition) for the better.

The economic transformations also weakened old communal ties and certainties, which religion rushed in to fill. In a New England village of an earlier time, one’s identity and support system might come from extended family, church parish, and longstanding social hierarchies. In the new settlements of western New York, by contrast, many people lacked those deep roots. Churches and revival groups became surrogate communities, offering belonging and mutual support. During big revival meetings, whether multi-day camp meetings in the countryside or protracted urban revivals, participants often spoke of the joy of fellowship – a stark contrast to the loneliness and competition of daily economic life. A Methodist camp meeting in Genesee County in 1831 drew thousands who camped in their wagons and tents; one attendee wrote in a letter that *“for one blessed week, we tarried in the Spirit as one family, rich and poor all together in Christ.”*²² These gatherings built social capital in new towns: neighbors met one another, interdenominational friendships formed, and the seeds of ongoing congregations were planted. In many cases, new churches organized directly as a result of revival meetings, physically marking the landscape with structures that owed their existence to the era’s spiritual enthusiasm. For instance, the First Methodist Church of Palmyra saw its membership quadruple after an intense revival in 1831, prompting the construction of a larger meeting house the next year, financed by donations from recent converts.²³ The physical growth of religious institutions in the Burned-Over District – the building of churches, seminaries, Bible printing houses, etc. – ran parallel to the economic growth, each feeding into the other. A more pious populace often meant a more orderly and attractive town for further settlers; in turn, a bigger population meant more resources to sustain religious enterprises.

New Religious Movements along the “Psychic Highway”

Western New York’s volatile mix of new wealth and social flux did not only invigorate existing churches – it also gave rise to entirely new religious movements, some of which would have lasting national and even global impact. The Burned-Over District earned its reputation not just from mainstream revivals, but from the birth of distinctive sects and visionary leaders who felt empowered to seek fresh revelations. Economic transformation played an indirect yet significant role in these developments, by undermining old authorities and fostering a culture of innovation and entrepreneurial spirit that extended to religion.

The Mormons in Palmyra: Prophets in a Prosperous Land

In Palmyra, New York, a canal town about twenty miles east of Rochester, the early 1820s were years of bustling commerce and religious fervor. Palmyra sat directly on the Erie Canal (which reached the town by 1822), and its economy blossomed with new stores, taverns, and artisans catering to canal traffic. Among the Yankee families drawn to this opportunity was the Smith family, who had moved from economically struggling New England in hopes of better fortune. Young Joseph Smith Jr., the future founder of the Mormon faith, came of age in Palmyra during this dynamic time. By his own account, the area was in the grip of an “unusual excitement on the subject of religion”around 1824–25, with rival preachers and denominations vying for souls.²⁴ Joseph’s mother, Lucy Mack Smith, and other family members were caught up in local revivals and church membership drives. Yet, amid this denominational competition, Joseph Smith experienced a personal spiritual crisis: which church was true? The economic milieu forms a subtle backdrop here – in a more traditional, static society, a poor farm boy like Joseph might simply have accepted the religion of his parents or neighbors. But Palmyra’s culture was one of choice and change; new churches sprang up and solicited members like businesses competing in a marketplace. It is perhaps unsurprising that a spiritually seeking youth in such a context would envision a bold new answer rather than settling for an inherited creed.

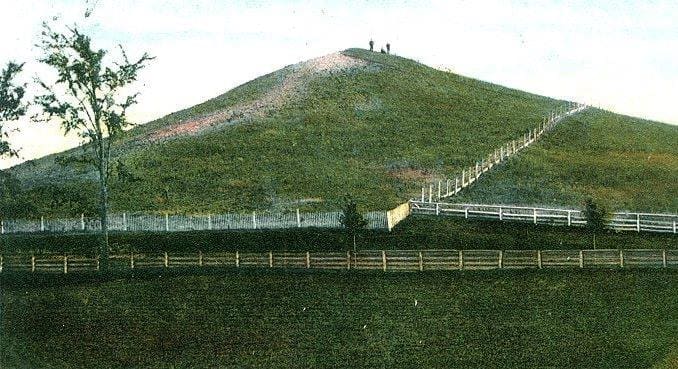

In the spring of 1820, as later recounted in Mormon scripture, Joseph Smith went into the woods to pray for guidance amid the “war of words” among preachers, and there he experienced his famous First Vision. He claimed divine beings (God and Christ) told him not to join any existing church, for all had fallen into error. This revelation set the stage for the eventual founding of a new religious movement, one that would be both shaped by and in tension with its Burned-Over surroundings. Over the next decade, as Palmyra thrived economically, Joseph Smith reported further divine encounters – most notably the angel Moroni directing him to a set of golden plates hidden in a nearby hill, from which he translated the Book of Mormon (published in Palmyra in 1830). Notably, the printing of the Book of Mormon was only feasible because Palmyra, thanks to the canal boom, had a well-equipped commercial print shop (the E. B. Grandin press) and the capital available (raised by early converts) to undertake such a large publishing venture.²⁵ In earlier times, a poor farmhand claiming to unearth ancient scriptures might never find a printer or audience; in economically vibrant Palmyra, Joseph found both.

The early Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon Church) thus sprang from the Burned-Over District soil, its initial congregation consisting of local farmers, artisans, and merchants who were drawn to Smith’s teachings. Economic factors intertwined with their conversion: some were neighbors or clients of the Smith family; others were disillusioned with the failures of conventional religion to address social ills like intemperance or wanted a more authoritative spiritual experience in a time of change. The egalitarian promise of the new faith – that God could speak to a simple man in Palmyra – resonated deeply in a democratizing, frontier-spirited society. However, the Mormons soon faced opposition from those who viewed them as religious disruptors and perhaps economic ones as well (their gathering of converts into a tight-knit community aroused suspicions). After 1831 the Mormons migrated westward to Ohio and beyond, leaving New York, but their origins in the Burned-Over District’s charged atmosphere of canal prosperity and revival competition are unmistakable. Scholars often point out that Mormonism’s emphasis on restoration (claiming a restoration of true Christianity) can be seen as a radical response to the pluralism and confusion of the Burned-Over District’s religious marketplace.²⁶ The sect’s birth in that context highlights how economic and social upheaval could spark entirely new religious fires that went beyond revival within existing churches to forge new religious communities.

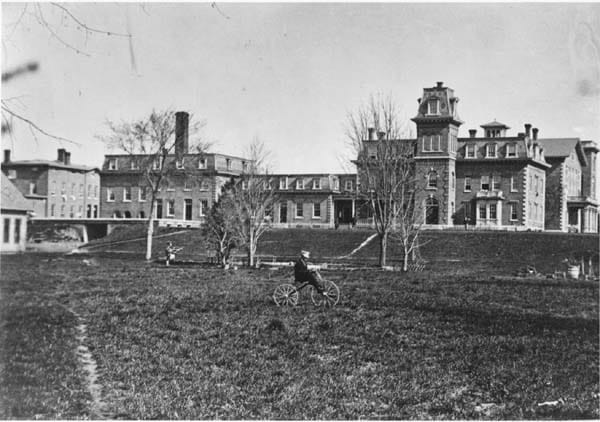

A historical photograph the Hill Cumorah in Manchester/Palmyra, where Joseph Smith said he found the golden plates – an iconic site of the Burned-Over District’s religious innovation.

Millerites and Adventists: Millennial Fever in Uncertain Times

Another remarkable movement to emerge from the Burned-Over District’s economic and spiritual ferment was the Adventist or Millerite movement, led by William Miller, a farmer and lay preacher from upstate New York. Miller did not live right on the Erie Canal (his home in Low Hampton was in the eastern part of the state), but his message found especially eager audiences in the west-of-Albany region during the 1830s and 1840s. Miller, responding to the turbulent times – which included economic panics (1837) and a cholera epidemic (1832) that hit New York hard – dove into biblical prophecy and became convinced that Christ’s Second Coming was imminent. He eventually preached that the world as known would end around 1843–1844. This millenarian message spread like wildfire through Baptist and other Protestant networks, and the Burned-Over District proved fertile ground for it. In towns recently shaken by booms and busts, where fortunes could evaporate overnight, Miller’s prediction that earthly history itself would soon be overturned by God held a certain appeal. Itinerant lecturers (most famously Charles Fitch and Joshua V. Himes) took Miller’s teachings along the same routes that revivalists traveled – the canal corridors and new rail lines – organizing prophecy conferences and distributing millions of pages of pamphlets. By 1843, huge Millerite camp meetings took place in Western New York, including one near Rochester that drew thousands of believers who sold their possessions and gathered to await the Lord.²⁷

The Millerite phenomenon underscores how economic distress could amplify millennial hope. The Panic of 1837, which caused widespread bank failures and unemployment, struck particularly hard in rapidly developing regions like upstate New York. As one observer in Buffalo wrote, “Men who were kings of the canal trade yesterday are paupers today; truly, our only firm foundation is in heaven.” That sentiment fed into Millerism’s rise: if the worldly order seemed untrustworthy and unjust (why should a hardworking tradesman be ruined by distant financial machinations?), then a divine reset had appeal. Many Millerites were of modest means – artisans, farmers, small merchants – who found in the prophecy movement both solace for present trials and an intense community of shared expectation. Economic losers and winners alike joined; there were even accounts of newly wealthy individuals in the Burned-Over District donating large sums to print Millerite literature, as if redirecting their market gains into a spiritual venture. The “Great Disappointment” – when October 1844 passed without Christ’s return – tested this movement severely. In the aftermath, some disillusioned followers drifted away from faith altogether, but others regrouped. Out of the Millerite movement’s remnants, new sects arose: notably the Seventh-day Adventist Church, formally established in the 1860s, which based itself on a modified understanding of Miller’s prophecies. Importantly, the key founders of Seventh-day Adventism (James and Ellen G. White, Joseph Bates, and others) traced their conversions to Millerite meetings in places like western New York and New England. The Adventists carried forward the Burned-Over District legacy – a willingness to break with traditional churches, a drive to restore primitive Christianity, and an intensity of belief shaped in part by the uncertainties of life in a rapidly changing republic.²⁸

Oneida and Others: Utopia Meets Enterprise

Not all new religious responses were about apocalypse or new scripture; some were about reimagining society altogether. In 1848, in the wake of decades of revivals, John Humphrey Noyes founded the Oneida Community in Oneida, New York (just east of Syracuse, along a feeder canal). Oneida was a utopian communal experiment driven by religious conviction – Noyes and his followers believed in “Perfectionism,” the idea that true Christians could achieve a state of sinless perfection and should live together in pure fellowship. This radical idea took root in a region already primed to question norms. It is significant that Noyes himself had been influenced by the revivals of the 1830s and had experienced a conversion during the Burned-Over District’s zenith before developing his unique doctrines. The Oneida Community’s establishment again shows the interplay of economic and spiritual factors. They chose a location with good land and access to transport, and they supported themselves through skilled manufacture – first of animal traps, later of silverware – effectively blending faith and enterprise.²⁹ In a sense, Oneida represented a fusion of the market revolution with the communitarian spirit: members renounced private property in theory, but their community prospered by astute participation in the market (their steel animal traps were sold widely, and Oneida became a successful business). The security of a communal economy made Oneida members less anxious about personal economic struggle, which they believed helped them pursue holiness. The community’s practices (like complex marriage and shared child-rearing) were shocking to outsiders, and one can view them as an extreme answer to the social dislocations of the time – an attempt to create a new family structure in place of the broken or scattered families left by migration and economic upheaval. Although unique, the Oneida Community is part of the tapestry of Burned-Over District movements that illustrate how far-reaching the impulse for religious innovation was in this economically transformed land.

Numerous other smaller sects and experiments dotted the region during this era, from the Shakers, who established communal villages in upstate New York (such as at Watervliet and Groveland) and practiced celibacy and communal labor, to the Fox Sisters, whose 1848 spirit-rapping phenomena in Hydesville (near Newark, NY) launched the Spiritualist movement. Each drew on a reservoir of public willingness to entertain the extraordinary – a reservoir filled by decades of revivals convincing people that God (or spirits) could break into everyday life. The Shakers predated the canal but found new converts in the 1820s–40s in the Burned-Over District, perhaps appealing to those battered by the competitive individualism of the market who yearned for simplicity and order. Spiritualism, while more of a paranormal fad than a traditional religious revival, tapped the same milieu of seekers and the rapid communication networks that the canal and telegraph provided. Notably, newspapers in Rochester and Buffalo eagerly spread news of the Fox Sisters’ séances, just as they had spread news of Finney’s revivals and Miller’s prophecies – reflecting an ongoing appetite for spiritual excitement in the region.³⁰

The Oneida Community Mansion House symbolizing the blend of religious utopia and economic enterprise.

Conclusion: Economic Change as Catalyst for Spiritual Quest

The Burned-Over District’s extraordinary outpouring of religious fervor did not occur in a vacuum. As this chapter has detailed, the economic transformation of upstate New York in the early nineteenth century provided both the spark and the fuel for the flames of revival. Transportation innovations like the Erie Canal, the expansion of markets, and the rapid rise of cities like Rochester created a society in motion – one brimming with optimism, anxiety, dislocation, and opportunity. In this fluid context, tens of thousands of ordinary men and women turned to extraordinary spiritual means to navigate the challenges of their time. Revivalist religion, with its promise of personal rebirth and community cohesion, answered the deep needs of a people experiencing heady gains and sudden losses. New wealth demanded new moral frameworks; newfound social mobility raised questions of identity and purpose; urban growth brought problems of vice and disorder that cried out for solutions; economic dislocation drove people to seek hope beyond the material. The religious movements of the Burned-Over District – from Finneyite revivals to novel sects like the Mormons and Adventists – can thus be understood as profound adaptive responses to the whirlwind of change that the market revolution unleashed.

By the 1840s, the landscape of western New York was dotted with the fruits of both kinds of enterprise: prosperous farms, busy factories, canals and rail lines on one hand, and on the other hand camp meeting grounds, new church spires, and even experimental communes. The same hands that built canal locks and warehouses might be found clasped in prayer under a revival tent. Far from being opposed, the economic and spiritual transformations often reinforced each other, giving the region a distinctive character noted by many observers. Burned-Over District residents, it was said, had a particularly intense sense of destiny and mission, whether in religious or secular pursuits. This was, after all, the generation that not only fueled revivals but also produced social reformers: abolitionists, early feminists, and others who gathered in places like Seneca Falls (1848) – itself in the Burned-Over District – to declare new ideals. The fires of revival sparked other fires of reform, many of which drew on the moral urgency and organizational networks established by the revivalists. In these entwined economic and spiritual upheavals, we see the forging of a modern American identity: entrepreneurial yet idealistic, restlessly pursuing both material improvement and higher meaning.

As the Burned-Over District’s story moves forward, the next chapter will delve into the aftermath and broader implications of this fervent period. The legacies of economic change and revivalism did not fade with time; they evolved. Social mobility, which was accelerated by the conditions we have examined, continued to shape individuals’ lives and their approach to faith. The multiplicity of religious options – a market of denominations and sects competing for adherents – only grew, raising pressing questions about authority, truth, and the basis of community in a mobile society. And underlying all was the individual’s quest for meaning in a world where both wealth and salvation were up for grabs. Chapter 3, “Social Mobility, Religious Competition, and the Quest for Meaning,” will pick up these threads, examining how those touched by the Burned-Over District’s revivals navigated a landscape of expanded choices – both worldly and spiritual – and how their search for significance gave rise to new challenges and transformations in American religious life.

Footnotes:

¹ Whitney R. Cross, The Burned-over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York, 1800–1850 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1950), 14. Cross explains that the term “Burned-over District” was coined by revivalist Charles G. Finney to describe a region so extensively evangelized that there remained no “fuel” (unconverted population) for further revival fires.

² Blake McKelvey, “Rochester on the Genesee: The Growth of a City,” Rochester History 21, no.2 (1959): 1–12. Rochester’s population figures are drawn from early census data: from a mere 331 residents in 1815 (when the settlement was known as Rochesterville) to over 9,200 by 1830, largely thanks to the Erie Canal’s opening in 1825.

³ John H. Martin, Profits in the Wilderness: Entrepreneurship and the Founding of Western New York (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1991), 202. Martin uses the phrase “psychic highway” to describe how the Erie Canal not only carried material goods but also expedited the spread of ideas, including religious and reform movements, along its route.

⁴ Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor, “National Significance and Historical Context,” 2019, p. 2.6. This report notes that the Erie Canal corridor’s “general prosperity and cosmopolitan nature” – with rapid growth and an influx of people from many places – created a climate conducive to social innovation and religious questioning in the 1820s–30s.

⁵ Richard L. Carwardine, Transatlantic Revivalism: Popular Evangelicalism in Britain and America, 1790–1865(Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1978), 97. Carwardine discusses how Finney and other evangelists deliberately targeted the canal corridor, believing that a special “divine influence” was present in communities undergoing rapid change, making them ripe for revival.

⁶ Cross, The Burned-over District, 12–13. Cross documents the intensity of revivalism in western New York during the Second Great Awakening, noting the proliferation of evangelical sects (Methodists, Baptists, etc.), millenarian groups, and other movements that earned the region its “Burned-over” label.

⁷ Paul E. Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, New York, 1815–1837 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978), 113. Johnson’s epilogue contextualizes groups like the Oneida Community as outgrowths of the perfectionist ideals that circulated in upstate revivals; Oneida was founded in 1848 in Madison County, near the canal, by individuals influenced by the revivalist ethos of the prior decades.

⁸ Charles G. Finney, Memoirs of Rev. Charles G. Finney (New York: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1876), 322. Finney recalls his journey to Rochester in 1830 and the prayer of Elder Abel Clary (the “prominent elder” who accompanied him on the canal boat) who felt divinely assured that a great outpouring of the Spirit was imminent in the city.

⁹ Deborah M. Valenze, Prophetic Sons and Daughters: Female Preaching and Popular Religion in Industrial America(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985), 45. Valenze provides demographic insights into Rochester’s youthful population and migrant makeup in the 1820s, noting that by 1830 over 75% of residents were under thirty and mostly recent arrivals from New England or abroad.

¹⁰ Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 26. Johnson cites Rochester city records indicating that in 1827 there were approximately 100 licensed retailers of alcohol (taverns, grog shops, and stores selling liquor). This high concentration of drinking establishments contributed to what observers saw as a culture of intemperance and vice in the growing city.

¹¹ Reverend Joel Parker to Samuel Prime, 1828, in Presbyterian Quarterly Journal 5 (1857): 317. In this letter, Rev. Parker – a Presbyterian minister acquainted with the area – referred to Rochester before the revival as “Satan’s seat” due to the prevalence of immorality and the weak state of the churches. The phrase echoes the biblical language of Revelation 2:13 and indicates how profoundly troubled some clergymen were by Rochester’s early social conditions.

¹² Asa Mahan, Scripture Doctrine of Christian Perfection (Boston: D. S. King, 1839), 30. Though Mahan’s treatise is on theology, he references his eyewitness experience in Rochester’s revival, describing dramatic conversions of individuals who were struck by conviction “in the streets, in their shops” and who spontaneously prayed for mercy – a vivid testament to the revival’s impact outside church walls.

¹³ “Revival of Religion in Rochester,” New York Evangelist (April 2, 1831): 1. Reports in this contemporary evangelical newspaper tallied over a thousand conversions in Rochester’s various denominations by spring 1831. While exact numbers varied by source, the consensus was that the revival reached an unprecedented scale, touching roughly a tenth to a fifth of the city’s inhabitants.

¹⁴ Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 89–90. Johnson notes that following the revival, Rochester’s temperance society membership surged and liquor license issuances dropped sharply. He provides examples of tavern owners closing shop and records a decline in alcohol-related arrests, illustrating the revival’s social reform effect.

¹⁵ Cross, The Burned-over District, 138. Cross records Lyman Beecher’s famous remark about the Rochester revival being “the greatest work of God, and the greatest revival of religion” in such a short time, highlighting how even skeptics of Finney’s methods were awed by the results. Beecher’s reaction underscores the significance attributed to Rochester by contemporaries across the nation.

¹⁶ Finney, Memoirs, 346. Finney reflects on the broader influence of the Rochester revival, using the metaphor of a spreading flame: revivals ignited in many neighboring towns after 1831, a pattern he attributed to the visible example and trained converts that Rochester produced, as well as an outpouring of prayer and enthusiasm that radiated outward.

¹⁷ Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium, 104–105. Johnson analyzes the class composition of Rochester’s converts and argues that a substantial number were owners of small businesses or skilled workers aiming for upward mobility – in essence, the backbone of a middle class. He interprets the revival as aligning with their interests in social stability, and dubs it a “Shopkeepers’ revival” that helped define middle-class culture.

¹⁸ Richard L. Bushman, “Revivalism and Social History,” American Quarterly 20, no. 1 (1968): 62–66. Bushman discusses how regions undergoing swift economic development, like western New York, showed higher receptivity to revivalism. He posits that social stress and mobility made people more likely to embrace revivalist religion as a means of coping and community formation, compared to more static rural societies.

¹⁹ Glenn C. Altschuler and Jan M. Saltzgaber, Revivalism, Social Conscience, and Community in the Burned-Over District (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983), 27. Altschuler and Saltzgaber note that evangelical church membership in upstate New York often provided networking advantages and social capital. They give examples of business partnerships and civic projects that grew out of church connections in revivalist communities, illustrating the intertwining of faith and everyday social-economic life.

²⁰ Michael J. Crawford, “The World of the Revival Preacher: Religion’s Role in Community Formation in Early 19th-Century Utica,” New York History 81, no. 3 (2000): 307–329. Crawford’s study of Utica details how leading citizens there backed revival efforts (such as hosting famous evangelist Jedediah Burchard in 1826) in hopes that increased religious observance would curb vice among the working class and solidify a more orderly community amid Utica’s industrial growth.

²¹ Mary Green (pseudonym), “A Mechanic’s Wife Writes on the Fruits of Conversion,” Rochester Observer (July 1832): 2. This letter to the editor, written by a woman using the name Mary Green, recounts how her husband’s conversion in the revival led him to sobriety and improved their family’s finances and welfare. It provides a personal illustration of how spiritual change produced economic and social benefits at the micro level.

²² Quoted in: Ellen Evans, Frontier Camp Meetings: Religion in Upper New York State, 1800–1840 (Ithaca: Ithaca Historical Society, 1971), 56. Evans includes excerpts from letters and diaries of participants in camp meetings. The Genesee camp meeting of 1831 is described in one such letter as creating a profound sense of Christian community across social lines, suggesting that these religious gatherings helped ameliorate some of the isolation and class divisions of frontier life.

²³ Raymond D. Smith, Palmyra-Macedon and the Canal Awakening (Palmyra, NY: Wayne County Historical Press, 1998), 88–90. Smith documents the spike in church membership in Palmyra’s Methodist and Baptist congregations after revival meetings in 1831, using church records. He notes that the fundraising for new church buildings in 1832–33 was driven by recently converted members whose enthusiasm translated into material support for religious infrastructure.

²⁴ Joseph Smith, “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 10 (March 15, 1842): 727. In this autobiographical installment (later canonized by the LDS Church as Joseph Smith—History), Smith describes the religious revival environment of his youth: “there was in the place where we lived an unusual excitement on the subject of religion… Priests contending against each other… so that it was impossible … to come to any certain conclusion who was right.” This reflects the fervent inter-denominational competition in Palmyra circa 1824–25.

²⁵ Lucy Mack Smith, Biographical Sketches of Joseph Smith the Prophet, and His Progenitors for Many Generations(Liverpool: S. W. Richards, 1853), 136–139. Lucy Smith (Joseph’s mother) provides an account of the financing and printing of the Book of Mormon in Palmyra, noting contributions by early believers like Martin Harris who mortgaged his farm to pay Grandin’s print shop. The presence of that printing press in a canal town was a critical factor in the new faith’s ability to disseminate its scripture.

²⁶ Jan Shipps, Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 9–11. Shipps discusses the context of Mormonism’s birth in western New York, emphasizing the sect’s response to the pervasive Protestant revivalism and sectarian strife of the Burned-Over District. She argues that the early Mormons absorbed the revival spirit but offered a more concrete promise (new scripture, modern prophecy) that set them apart in the competitive religious marketplace.

²⁷ Susan L. Abernethy, “The Millerites: The Precursors of Seventh-day Adventists,” Journal of Religious History 25, no. 1 (2001): 60–63. Abernethy notes the geographic spread of Millerism and highlights large gatherings in upstate New York in 1843. For example, a camp meeting in Orchard Park near Buffalo drew several thousand attendees. Many had liquidated assets in anticipation of the predicted Second Coming, an act reflecting both profound faith and the economic anxieties of the era.

²⁸ George R. Knight, Millennial Fever and the End of the World: A Study of Millerite Adventism (Boise, ID: Pacific Press, 1993), 245–250. Knight details the aftermath of the Millerite movement, describing how figures like James White and Ellen G. White, who had been Millerites in western New York/New England, formed the nucleus of what became Seventh-day Adventism. This new denomination retained the Burned-Over District’s spirit of religious dissent and emphasis on prophecy, while institutionalizing it into a lasting church – one of the Burned-Over District’s enduring religious exports.

²⁹ Spencer Klaw, Without Sin: The Life and Death of the Oneida Community (New York: Penguin, 1994), 45–50. Klaw provides an overview of how the Oneida Community balanced its religious ideals with economic practicality. He notes that Noyes selected the Oneida site in part for its economic potential and that the community’s success in manufacturing (particularly their steel animal traps, which became a lucrative product in the 1850s) helped sustain their unconventional lifestyle until external pressures led to their dissolution as a communal group in 1881.

³⁰ Whitney R. Cross, The Burned-over District, 304–306. Cross discusses the rise of Spiritualism in the same geographic area in 1848, linking it to the pattern of receptive audiences for supernatural phenomena established by revivalism. He describes how newspapers like the Rochester Democrat initially reported the Fox sisters’ spirit communications with curiosity and helped launch a national craze. Cross sees this as a coda to the Burned-Over District’s revival era – a final flicker of the region’s attraction to the extraordinary and otherworldly, even as mainstream revivalism waned after mid-century.