The Burned-Over District and the Second Great Awakening – A Crucible of Religious Fervor

The Second Great Awakening was a profound religious revival that swept across the United States in the early 19th century, and it found its most intense expression in a swath of western New York state known as the “Burned-Over District.” This region—roughly between Albany and Buffalo—earned its evocative moniker due to the extraordinary frequency and intensity of revival fires that blazed through its towns and villages, leaving few souls unconverted in their wake. The term itself was popularized by evangelist Charles Grandison Finney, who observed that the area had been so thoroughly evangelized that no spiritual “fuel” (unconverted population) remained to “burn” (convert). Finney’s vivid metaphor speaks to how completely the fervor of revival had consumed the region’s religious landscape by the 1830s. This chapter explores the origins and development of that fervor, examining the unique social, economic, and cultural factors that made western New York a breeding ground for religious enthusiasm, as well as the key figures and events that shaped this pivotal moment in American religious history.

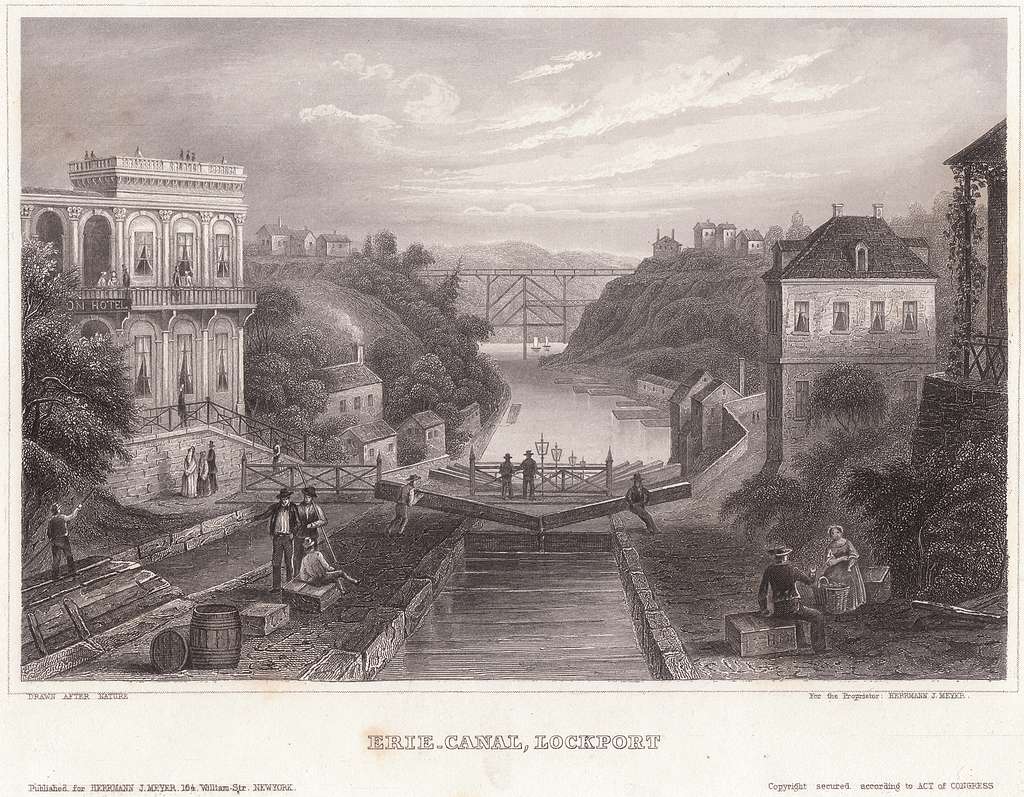

The Second Great Awakening began nationally in the late 18th century (with roots in the 1790s) but gained significant momentum in the early 19th century, particularly during the 1820s and 1830s. While this revival movement touched many parts of the young United States—from the frontier camp meetings of Kentucky to the congregations of New England—it found particularly fertile ground in upstate New York. The Burned-Over District became, as one historian describes, a veritable “crucible” of religious fervor where revival fires burned the hottest. Several factors converged here to kindle an unusually intense spiritual flame. The region was undergoing rapid population growth and economic upheaval in the early 1800s, fueled in large part by the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. The canal transformed the local economy by linking the Great Lakes to the Atlantic, turning small frontier settlements into thriving commercial centers virtually overnight. For example, the city of Rochester—a canal boomtown—saw its population skyrocket sixfold in a single decade (from about 1,500 in 1820 to over 9,000 by 1830) . Such explosive growth brought prosperity but also social disruption, dislocation, and a breakdown of traditional norms.

Amid the chaos of swift change, many people in western New York turned to religion for stability, meaning, and moral guidance. The revivals thus often functioned as a response to the problems of social order in rapidly growing communities. Historian Paul E. Johnson, in his influential study of Rochester, argues that the evangelical revivals there were a way for the emerging middle class to impose moral order on a turbulent boomtown. Indeed, Rochester’s revivals of 1830–31 coincided with efforts to promote temperance, sabbath observance, and disciplined living among a diverse influx of canal workers, migrants, and new entrepreneurs. Finney and other revivalists preached personal salvation but also hammered on themes of personal conduct, denouncing alcohol, theater, and vice. Their message resonated especially with those anxious about the social ills accompanying rapid growth. As one contemporary observer noted after a dramatic Rochester revival, “the whole character of the city was changed”: the only theater in town closed down, taverns emptied out, and crime rates dropped precipitously (reportedly by two-thirds in the following year) . Even some civic leaders were swept up in the religious excitement—among them a local militia colonel and future district attorney who experienced conversion, emblematic of how deeply revivalism penetrated the community . In short, evangelical Christianity became a powerful force for social cohesion and reform in a region buffeted by change.

Finney’s Revivals and New Measures: Central to the Burned-Over District’s fervor was the work of Charles G. Finney (1792–1875), the era’s most famous revival preacher in the North. Finney conducted revival meetings throughout upstate New York in the 1820s and 1830s, including spectacularly successful campaigns in Rome (1826), Rochester (1830–31), and elsewhere . Breaking with earlier Calvinist orthodoxy, Finney taught that revival was not a miraculous event but a result of proper human agency and technique – essentially, a process that could be encouraged and organized. He introduced innovative “new measures” to revival meetings, aiming to stir people’s emotions and prompt immediate decisions for Christ. These measures included the “anxious bench,” an early form of altar call where those under deep conviction of sin sat up front to be prayed for, and the public praying of women in mixed congregations, a practice then considered radical . Finney also scheduled protracted multi-day meetings and employed direct, colloquial preaching that appealed to common folk. Such methods, along with a potent message of free will salvation, helped democratize religious participation . Finney’s revivals achieved astonishing results: churches swelled with new members, and entire communities adopted more strict moral norms in the wake of his campaigns. Even other preachers marveled at the spiritual excitement that Finney left in his trail. A correspondent from Utica in 1831 reported that religion had become the “chief concern” of nearly everyone in Rochester, describing scenes of crowded prayer meetings and converts numbering in the thousands . The Burned-Over District’s religious culture was thus indelibly shaped by Finney’s revivalism, which combined passionate oratory, social network organizing, and a message of personal and societal regeneration.

While Finney and his fellow evangelical Protestants ignited most of the fires in the Burned-Over District, the region’s religious ferment extended beyond mainstream revivals. Western New York became famously fertile soil for new religious movements and breakaway sects that arose alongside the Second Great Awakening. During these decades, an array of home-grown prophets, preachers, and visionaries introduced novel doctrines and founded enduring religious communities. For instance, in 1830 Joseph Smith, a young man from the village of Palmyra, published the Book of Mormon and organized the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormonism) in that very region. Smith later recalled that his boyhood in western New York coincided with an “unusual excitement on the subject of religion” that saw preachers of various denominations vying for converts and fervent camp meetings in the countryside . Indeed, “the whole district of country seemed affected” by revival zeal, Smith wrote of the period around 1820, as “great multitudes” joined churches amid a spiritual frenzy . Mormonism was one product of this fervid religious competition—born directly out of the Burned-Over District’s atmosphere of revival and prophetic expectation. A decade later, in the 1840s, the region was also a center of the Millerite movement, a nationwide Adventist revival led by William Miller, who preached the imminent Second Coming of Christ. Miller’s end-of-the-world prophecies electrified thousands in upstate New York; tens of thousands more across the country embraced his prediction that Christ would return in 1843–1844 . One Millerite believer, Ellen G. White, later recounted how “far and wide spread the message”of Christ’s soon coming during those years, awakening a mix of hope and urgency in congregations everywhere . Although the specific date of Christ’s return proved mistaken (an episode known as the “Great Disappointment” of October 1844), the Millerite revival left a lasting legacy: from its ashes emerged new denominations such as the Seventh-day Adventist Church, guided in part by visionary leaders like Ellen White in the subsequent decades. In addition to Mormonism and Adventism, the Burned-Over District gave rise to other religious innovations including the Spiritualist movement (sparked by the Fox Sisters of Hydesville, who claimed spirit communication in 1848) and various utopian communes (such as the Oneida Community in the 1840s). The sheer concentration of new sects and bold religious experiments earned the region a reputation as, in the words of one scholar, “the cradle of America’s new religious pluralism” .

It is worth noting that not everyone viewed these enthusiastic religious upheavals positively. Some more traditional clergymen complained that revivalists, in their quest for mass conversions, bred instability or fanaticism. The Presbyterian minister Lyman Beecher initially worried that Finney’s emotional tactics would “bring about dangerous extremes,” though he later acknowledged the overall positive moral impact of the revivals . Conversely, revival advocates like Finney argued that vigorous new religious expression was needed to awaken a populace that had grown complacent. The Burned-Over District became a microcosm of the era’s tensions between old and new religious sensibilities—between established churches and upstart movements, between sober doctrinal religion and ecstatic popular revivalism. In this roiling religious cauldron, charisma and grassroots energy often trumped hierarchy and tradition, leading to a democratization of faith that mirrored the Jacksonian democratic spirit of the age . Ordinary farmers, artisans, and women (who were often excluded from formal power) found voice and agency in revival meetings, prayer circles, and new sectarian communities. This democratizing impulse helps explain why western New York was so receptive to itinerant preachers and self-taught prophets: the social fluidity of a frontier-turned-boomtown region eroded old elites and emboldened new leaders to emerge from the ranks of common people .

However, the standard narratives of the Burned-Over District—focused on charismatic preachers, fervent converts, and new sect formation—often overshadow deeper historical contexts of the region. To fully understand why this area became such hotbed of revivalism, we must widen the lens beyond the revival meetings themselves. Several additional factors deserve attention: the indigenous history of the land, the political climate of the early 19th-century frontier, and the environmental and agricultural conditions that underpinned settlers’ lives. These elements, though sometimes treated as background, fundamentally shaped the religious culture of western New York. Recognizing their role will help us develop a more holistic understanding of the Burned-Over District’s significance.

Indigenous Presence and Legacy

Long before it was dubbed the “Burned-Over District,” western New York was the homeland of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois), specifically the Seneca and other nations of the confederacy. The transformative revivals of the early 1800s occurred on lands that had only recently been wrested from Native American control, often by violent and coercive means. During the American Revolution, General George Washington ordered the Sullivan–Clinton Campaign of 1779, a brutal offensive that burned Iroquois towns and cornfields across upstate New York . This campaign destroyed upwards of 40 Haudenosaunee villages, decimated food supplies, and forced thousands of Iroquois to flee, thereby opening the frontier for American settlement . In the decades that followed, a series of treaties—often signed under duress—stripped the Iroquois of most of their territory in New York. By the turn of the 19th century, the vast majority of western New York’s fertile lands had been sold or granted to white settlers, and the once-dominant Iroquois confederacy was confined to a few small reservations or had relocated to Canada.

This context of dispossession formed the backdrop to the Burned-Over District revivals. The influx of farmers and town-builders who kindled revival flames did so on land profoundly marked by colonization and indigenous loss. Understanding this history is crucial for a complete picture of the region’s spiritual landscape. Not only were Native Americans the displaced predecessors to the settlers; they too experienced religious ferment during this era, though of a different kind. In fact, the early 19th century brought a significant indigenous revitalization movement among the Seneca led by the prophet Handsome Lake. In 1799, as the Seneca reeled from land loss, social upheaval, and the trauma of war, Handsome Lake (Sganyodaiyo) fell ill and was believed near death when he had a series of visions . These spiritual revelations—blending traditional Iroquois beliefs with ethical principles partly influenced by Quaker and Christian teachings—sparked a revival within the Seneca community known as the Longhouse Religion. Handsome Lake’s message emphasized temperance, peace, and a return to righteous living, and it helped reinvigorate the Seneca at a time of crisis . This parallel revival (beginning just a few years before the Second Great Awakening took hold among white settlers) underscores that spiritual renewal was not unique to the settler population. Both dispossessed indigenous people and incoming Yankees were seeking meaning and stability amid disruptive change, though they did so in very different ways.

By centering the experiences of Native Americans, we recognize that the Burned-Over District’s story is not only about evangelical Protestantism’s triumphs; it is also about what came before and alongside that revival movement. The revivals occurred in a space made available by Native American removal, and they proceeded largely without acknowledging the tragedy and resilience of the land’s original inhabitants. Occasionally, the two worlds did intersect—for example, some missionaries in the region tried to evangelize the Iroquois, and a few Native Americans, such as the Onondaga chief Orringhio, attended camp meetings or converted during revivals. Yet, for the most part, the booming religious culture of the Burned-Over District existed in a settler society bubble. Modern scholarship insists that we situate the Second Great Awakening in this fuller context, understanding that the “spiritual burning” of the frontier had a literal antecedent in the burning of indigenous longhouses and crops decades earlier. This perspective invites a more sober appreciation of the region’s history—one that honors the memory of Native communities even as it examines the settler revivals that followed.

Political Influence and Local Governance

Another often underexplored dimension of the Burned-Over District is its political climate and the interplay between revivalism and local governance. The religious fires in upstate New York did not burn in isolation from political currents; on the contrary, the fervent religious atmosphere both influenced and was influenced by contemporary politics. The 1820s–1840s in this region saw the rise of populist movements and third-party ventures that intersected with the moral imperatives of revivalists. For example, western New York became the epicenter of the Anti-Masonic movement, one of America’s first third-party political crusades. The Anti-Masonic Party, formed in the late 1820s after the mysterious disappearance (and presumed murder) of William Morgan (an ex-Mason who had threatened to expose Masonic secrets in Batavia, NY), quickly gained support among the same Protestant evangelical circles ignited by the Second Great Awakening. Many revivalist Christians viewed Freemasonry as a secretive, elitist, and morally suspect institution; thus, opposition to Freemasonry often went hand-in-hand with the religious reformist zeal of the time . Anti-Masonic newspapers and speakers peppered their rhetoric with biblical references and calls for moral purification of society. By the early 1830s, the Anti-Masonic Party in New York had attracted a substantial following of evangelicals who saw their political activism as an extension of their religious convictions. The party’s strongholds were squarely within the Burned-Over District, and it championed causes like honest government and temperance which complemented the revivalists’ message of personal morality. Although the Anti-Masonic Party was short-lived (fizzling out by the late 1830s), it foreshadowed the political mobilization of evangelical Protestants that would later define movements such as abolitionism and the new Republican Party in the 1850s .

Local governance in revivalist communities was also shaped by the era’s religious enthusiasm. In towns touched by revival, newly converted citizens often pressed for laws and ordinances reflecting their evangelical values. For instance, villages instituted stricter observance of the Sabbath (sometimes by local ordinance closing businesses on Sunday), cracked down on alcohol sales (leading to early temperance regulations at the municipal level), and supported the establishment of moral reform societies. In Rochester after the Finney revivals, converts helped found and sustain organizations like the Society for the Promotion of Temperance and the Moral Reform Society, which aimed to rid the city of prostitution and drunkenness . These organizations in turn lobbied the city government for supportive measures. It is telling that some of the region’s prominent political leaders had deep revivalist connections. William H. Seward, who became Governor of New York in 1839 (and later U.S. Secretary of State), was influenced by the evangelical fervor of the time—his wife Frances Seward was an active abolitionist from a revivals-swept family, and both were friends with radical evangelical abolitionists in the Burned-Over District. Another example is Gerrit Smith, a wealthy landowner in central New York, who experienced a religious conversion and became a leading abolitionist and temperance advocate, even running for president on an anti-slavery ticket. Though Smith’s Eaton and Peterboro estates were just outside the traditional “burned-over” zone, he moved in the same circles of reform and revival. Meanwhile, on the grassroots level, one finds that many local officials (sheriffs, judges, town supervisors) in western New York were churchgoing men whose election campaigns highlighted their Christian morals. Revival meetings sometimes even took on a quasi-civic character: local magistrates and politicians might be publicly prayed for by name from the pulpit, and communities were urged to repent collectively for civic sins like lax law enforcement or neglect of the poor.

The cross-pollination of revivalist religion and politics in the Burned-Over District was perhaps most clearly manifested in the cause of abolitionism. Upstate New York was a hotbed of the anti-slavery movement, earning it another nickname as the “abolition swamp” in the 1830s and 1840s . Evangelical Christians, imbued with revivalist zeal, were among the earliest and loudest voices condemning slavery as a national sin. Many of Finney’s converts, for instance, left his meetings convinced that they must work not only for their own sanctification but also for the moral uplift of the nation by eradicating slavery. One of Finney’s distinctive teachings was the idea of “the perfection of society” – he argued that true conversion should lead a person to pursue the perfecting of the world around them, which in that era translated to activist reform movements . In 1835, a massive interracial anti-slavery revival meeting was held in Utica (just east of the Burned-Over District proper) under the auspices of the New York Anti-Slavery Society, famously broken up by a mob; significantly, the attendees included many western New Yorkers galvanized by their faith to demand immediate emancipation. It is no coincidence that the Underground Railroad had numerous stations in this region: churches and individual Christians offered their homes and barns as shelters for fugitive slaves. The Burned-Over District’s religious intensity thus bled naturally into political and social activism, helping to shape the agendas of local governance and contributing to the broader currents of American political life. In summary, revivalism provided both the moral vocabulary and the mobilizing networks for political causes, making the region a seedbed not only of new religions but also of reformist and populist political energy.

Environmental Factors and Agricultural Practices

In exploring why the Burned-Over District was so primed for religious upheaval, we must consider the environmental and agricultural backdrop that conditioned the lives of its inhabitants. The daily existence of most people in early 19th-century upstate New York was tied to the rhythms of nature and the cycles of farm life. Environmental hardships and bounty alike could influence the receptivity of communities to revivalism. One striking example is the effect of the 1816 “Year Without a Summer.” Caused by the massive 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, 1816 saw freakish cold weather and frosts even in summer months across the northeastern United States. Crops failed on a large scale in New England and upstate New York, leading to shortages and economic distress. This climatic disaster prompted a significant migration of farming families out of Vermont and western Massachusetts into western New York (and further west) in search of more reliable land . Some historians have suggested that the collective anxiety and hardship caused by the Year Without a Summer contributed to heightened religious fervor in its aftermath . Churches reported that in 1816–1817, revivals broke out in several places as people interpreted the unusual weather as a divine warning or punishment. In the words of one historian, “many feared an angry God was punishing them” with the unseasonable frosts, and they flocked to churches seeking solace and repentance . While direct causation is hard to prove, it is clear that environmental stressors primed populations for religious renewal. The memory of 1816’s near-apocalyptic weather would have still been fresh when, just a few years later, Finney and others began calling for repentance in the Burned-Over District. The psychological impact of crop failures, along with diseases like the cholera epidemic of 1832 (which hit New York in the same period), likely made themes of judgment and salvation more poignant, and the promise of God’s favor more appealing, to the agrarian communities.

On the other hand, the long-term environmental conditions of western New York were generally favorable to prosperity, which also played a role in the revival dynamic. The region boasted fertile soils—former Iroquois agricultural land—that yielded abundant wheat, apples, and other crops. By the 1820s and 1830s, many farmers in the Burned-Over District were enjoying relative success, producing surpluses for market thanks to the transportation revolution of the Erie Canal. This agricultural prosperity gave rise to a new middle class of landowners and millers, who often became pillars of local churches and sponsors of revival meetings. We might think of these well-off farmers and merchants as the patrons of the Second Great Awakening: they had the means to donate funds for building new churches, hosting itinerant preachers, and publishing religious tracts. At the same time, prosperity brought new temptations and vices. Boom times in canal towns attracted gamblers, saloon-keepers, and opportunists. The presence of wealth and commercialism on what a generation earlier had been pure wilderness created a cultural tension: material progress versus spiritual purity. Revival preachers capitalized on this tension by warning against the love of money and worldly luxury, urging people not to be swept away by the gleam of prosperity. Many farmers who had cleared their land through literal burning of trees and underbrush could relate viscerally to the Biblical imagery of “fire,” “sifting,” and “harvest” that revivalists so often employed. The language of revival sermons was replete with agrarian metaphors familiar to an audience of cultivators: fields ripe for harvest (souls ready to be saved), fallow ground of the heart that needed plowing, the former and latter rains of God’s spirit, etc. This resonant symbolism helped align spiritual renewal with the cycles of nature that governed rural life .

It is also interesting to note how the physical landscape might have facilitated the spread of revivalism. Western New York is a region of rolling hills, valleys, and long winters. In the colder months after harvest time, rural folks had more leisure for extended revival meetings. The winter of 1830–31, for instance, when Finney held meetings nightly in Rochester for months, was an ideal time for farmers and canal workers (whose work was seasonal) to attend protracted services. Moreover, the Erie Canal and feeder roads served as conduits not just for goods but for ideas and itinerant ministers. Preachers could travel more swiftly along the canal corridor, hopping from one village to the next. News of a striking conversion or a dramatic miracle at one meeting would travel down the canal line via boatmen and merchants, generating buzz in the next town. In essence, the improved infrastructure and communication networks of the region—an environmental modification of the landscape—acted as an accelerant for revival fire. Had western New York been isolated and difficult to traverse (as it was in the 18th century), its revivals might have remained more localized phenomena. By the 1820s and ’30s, however, the geography was knit together tightly enough to allow a revival in one location to quickly inspire others in distant towns.

Finally, some scholars have pointed out an intriguing if speculative connection between the “burned-over” metaphor and the region’s agricultural practice of burning fields. Frontier farmers commonly used fire to clear land of stumps and to renew pasture (the ash serving as fertilizer). Early residents of the area would have been quite familiar with the sight of blackened, burned-over fields in the aftermath of these controlled burnings. It is conceivable that Finney or others adopted the “burned-over” imagery partly from this agricultural context, comparing spent fields to communities that had been thoroughly cultivated by evangelism. Whether or not this is true, it reminds us that the natural environment and human cultivation of the land were ever-present backdrops to the religious drama unfolding in the Burned-Over District. Nature, in a sense, both provoked spiritual seeking (through calamities like 1816) and provided apt metaphors for revival (through farming life).

Conclusion: Toward a Holistic Understanding

The Burned-Over District of New York was, by any measure, a remarkable theater of religious energy and innovation. In the span of a few decades, this region witnessed evangelical Protestant revivals that converted thousands and reshaped communities, the birth of new religious movements that would profoundly influence American faith (from Mormonism to Adventism and beyond), and the rise of reform crusades that tackled some of the greatest moral and political issues of the day. Historians like Whitney R. Cross, who first studied the region in depth in The Burned-over District (1950), emphasized the intensity of religious enthusiasm that made this area unique. Subsequent scholars have built on that work, debating the causes and significance of the revivals. Some argue that the Burned-Over District’s revivals were the inevitable product of social strain in a frontier economy, a safety-valve for communities under stress. Others highlight the role of charismatic leaders and theology, suggesting that without Finney’s innovative methods or the populist Arminian message of free salvation, the movement would not have gained such traction . Still others note the importance of networks and infrastructure (like the canal) in creating a critical mass of converts and sustaining the momentum of revival.

What becomes clear from our examination in this chapter is that no single factor can explain the Burned-Over District’s religious fervor. It was the convergence of many forces—social, economic, cultural, political, and environmental—that created a crucible in which the fires of the Second Great Awakening burned so bright. A holistic understanding recognizes, for instance, that the zeal of a Finney sermon in 1831 cannot be separated from the fact that his audience lived in a rapidly changing canal town, or that their parents had survived a year of frosts and famine in 1816, or that the land they sat upon had been taken from the Seneca not long before. The interplay of faith with frontier circumstance meant that revivalism in western New York was at once a deeply spiritual event and a manifestation of broader historical currents—the democratization of America, the market revolution, the displacement of indigenous peoples, and the contest of values in a young republic. By weaving these threads together, we gain a richer appreciation of why the Burned-Over District became, as one journalist later quipped, “the Blazed-Over District, the well-nigh scorched district” of American religiosity .

In the chapters that follow, we will dive deeper into specific facets of this story. We will explore how economic transformation and class structure influenced the course of revival (Chapter 2), examine individually the new religious movements and charismatic figures that emerged from the Burned-Over milieu (Chapter 3), and analyze the lasting impact of the Second Great Awakening on American society and culture (Chapter 4). By providing a comprehensive and balanced analysis—one that accounts for both the heavenly and earthly dimensions of the Burned-Over District—we hope to enrich the understanding of this dynamic episode in American religious history. Ultimately, the tale of the Burned-Over District reminds us that religious fervor does not occur in a vacuum: it is ignited at the intersection of spiritual longing with the tangible realities of time and place. In that fertile intersection, early nineteenth-century western New York became ground zero for a spiritual bonfire whose light would cast long shadows over the American landscape for generations to come.

Sources:

- Cross, Whitney R. The Burned-over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York, 1800–1850. Cornell University Press, 1950.

- Johnson, Paul E. A Shopkeeper’s Millennium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, New York, 1815–1837. Hill and Wang, 1978.

- Smith, Joseph. Joseph Smith–History 1:5–6 (1838 account of early life). Pearl of Great Price.

- White, Ellen G. The Great Controversy. 1888. (Chap. 20, “A Great Religious Awakening”).

- Finney, Charles G. Autobiography of Charles G. Finney. 1876. (Finney’s “burned-over district” remark).

- “Charles Grandison Finney and the Second Great Awakening.” Christian History, no. 20, 1988.

- North Country Public Radio, “1816: The Year Without a Summer.”

- Encyclopedia.com, “Handsome Lake.”