Moral Reform in the Burned-Over District

Revivalism and Community Transformation

The religious fervor of the Burned-Over District did not remain confined to church pews or camp-meeting tents. It spilled over into everyday life and fundamentally rewove the social fabric of upstate New York in the early nineteenth century. Revival meetings were community events that cut across class lines and brought together men, women, and children in shared spiritual experience. The conversions and evangelical zeal ignited by revivalists like Charles Grandison Finney quickly translated into a collective impulse to “do good” in the world. Finney himself preached that true religion must exert influence beyond the sanctuary: “The Church must take right ground in regard to politics… [Christians] must do their duty to the country as part of their duty to God… God will bless or curse this nation, according to the course Christians take in politics.”[^1] In other words, personal salvation was seen as incomplete without social redemption. The result was an outpouring of moral enthusiasm that would reshape institutions of family, community, and civil society.

Evangelical revivalism introduced new forms of social interaction and communal bonds. Camp meetings and protracted revivals fostered a sense of shared identity among participants, erasing (at least temporarily) some distinctions of status or background. Neighbors prayed and sang together, wept over their sins side by side, and rejoiced in one another’s conversions. This created what one historian calls an “evangelical community” knit together by common values and emotional experience[^2]. New converts often joined interdenominational benevolent societies—charitable and reform organizations dedicated to tackling social ills. In towns across the Burned-Over District, it became typical for churches to sponsor or encourage societies for Bible distribution, Sabbath schools for youth, and missions to the poor and the unchurched. The surge of religious enthusiasm thus strengthened communal ties: citizens were bound not only by locality or kinship, but by a shared moral mission.

At the same time, revivalism could blur traditional class lines even as it helped consolidate a burgeoning middle class culture. Many of the evangelical converts were from the ranks of artisans, shopkeepers, and farmers—respectable working people aspiring to self-improvement and stability. The revivals offered them a language of moral respectability and discipline. Indeed, in the boomtown of Rochester, where Finney led a spectacular revival in 1830–31, the nascent middle class embraced evangelical religion as part of a drive for order and reform in a rapidly growing city[^3]. Historian Paul E. Johnson's A Shopkeeper's Millennium meticulously documents how Finney's preaching didn't just save souls—it fundamentally restructured Rochester's social order, creating the urban middle class that would champion temperance, abolition, and moral reform throughout the century."The old colonial elites (often Anglican or Episcopalian in background) were relatively less prominent in these democratized revival meetings. In their place, tradesmen, merchants, and professionals took on leadership roles in churches and reform societies. This shift has led scholars to characterize the Second Great Awakening in upstate New York as a “cradle of the middle class,” where Victorian values of industry, sobriety, and familial virtue first took root[^4].

In short, the social hierarchy was being reshaped: moral standing and piety began to carry as much weight in the community as wealth or pedigree.

Family Life and Gender Roles Under Revival Influence

Revivalism also reverberated through the intimate sphere of family and gender relations. The evangelical emphasis on individual conversion meant that wives, husbands, and children were all urged to examine their souls—and this sometimes upended traditional authority within the home. In many households, women emerged as the spiritual pillars, leading family prayers or gently admonishing wayward relatives to reform. The Burned-Over District’s ethos empowered women in subtle but significant ways. Charles Finney’s revivals, for example, broke with convention by allowing women to pray aloud in mixed meetings, legitimizing a more public religious role for women[^5]. Wives and daughters who experienced conversion gained a new sense of duty and confidence to act as moral guardians of their families. They might persuade a drinking husband to take the temperance pledge or encourage their neighbors to attend church. The ideal of “Christian motherhood” took hold: women were seen as moral instructors of children and the agents of piety within the home[^6]. This aligned with the broader 19th-century notion of “Republican Motherhood”and the emerging cult of domesticity, but with an evangelical twist—home was a hearth not only of domestic virtue but of religious devotion.

Yet the revivals also cracked open the door to women’s activism beyond the home. Women in the Burned-Over District formed some of the earliest female-run charitable associations, such as mothers’ prayer groups and female mission societies. Through these organizations, women gained experience in leadership, fund-raising, and public speaking—skills that would later prove invaluable to movements like abolitionism and women’s suffrage. Historian Nancy A. Hewitt, in her study of Rochester, notes that women converts used the networks forged in church to organize female reform societies, thereby extending their influence from the private sphere into the public arena[^7]. It was a delicate negotiation: these women justified their public work as an extension of motherly duty to protect the moral well-being of the community. By operating within the language of piety and virtue, they were able to traverse traditional gender boundaries without overtly challenging them—at least at first. In time, however, the confidence and organizational acumen women developed in church-based activities gave rise to more explicitly feminist awareness, as we will see in the discussion of the women’s rights movement.

Not everyone welcomed these shifts in gender dynamics. More conservative clergy and laymen grew uneasy with women’s growing visibility in religious gatherings. In 1837, for instance, the Congregational ministers of Massachusetts (in a famous Pastoral Letter) warned women to stop giving public talks, saying it would ruin female modesty and undermine social order[^8]. While that letter was directed at abolitionist women in New England (the Grimké sisters), it reflected a broader anxiety also present in New York’s evangelical circles: how far should women’s influence reach? In the Burned-Over District, revival leaders like Finney generally supported a greater role for women in ministry efforts, which created tensions with more traditionalist factions. This debate was an early sign that the quest for moral reform would eventually lead women to question why their “sphere” had to remain only the hearth and home.

From Personal Salvation to Social Reform: An Ethos of Improvement

Underlying all these transformations was a profound theological shift: the revivals imbued people with a belief in human agency to improve society, guided by Christian principles. Many revivalists in upstate New York embraced a post-millennial outlook—the idea that the Kingdom of God on earth would be established gradually through human effort, paving the way for Christ’s return. This optimistic theology encouraged believers to see societal reform as part of God’s plan. If sins like intemperance, slavery, and ignorance could be eliminated, humanity would progress toward a millennial age of peace and righteousness. The Burned-Over District earned its moniker in part because it was “ablaze” not only with religious emotion but with schemes to perfect the world. One contemporary observer quipped that the region was so permeated with reformist zeal that you could hardly throw a stone without hitting some kind of society for improving something.

Ministers actively taught that conversion carried a mandate for benevolence. Evangelist Theodore Dwight Weld (himself a disciple of Finney’s revivals) often emphasized that true Christian conversion meant hating sin in all its forms, not just in one’s own heart but in the surrounding society[^9]. Converts were encouraged to channel their new-found spiritual energy into concrete action—what one historian calls “the impulse to reform” that inevitably followed the revival experience[^2]. In practical terms, this meant founding or joining voluntary associations to combat every imaginable moral evil. By the 1830s and 1840s, western New York was teeming with organizations dedicated to causes ranging from Sabbath observance to the alleviation of poverty and the rehabilitation of criminals. A robust associational culture flourished, linking towns across the region in a web of communication about reform. Local newspapers eagerly reported the meetings of temperance societies or anti-slavery lectures, spreading the fervor to those who hadn’t personally experienced a Finney-style revival.

It is important to note that this surge of moral reform was not imposed from above by any government; it was a grassroots movement sustained by ordinary citizens and church folk. The Second Great Awakening coincided with Andrew Jackson’s era of expanding democracy, and there was a democratizing spirit in the reform campaigns as well. Anyone – farmers’ wives, freed slaves, small-town schoolteachers, itinerant preachers – could start a society or sign a petition. The only credentials needed were moral conviction and enthusiasm. In the Burned-Over District, a new kind of civic activism took root, blurring lines between religious duty and political action. This was the seedbed from which many of America’s major antebellum reform movements sprang. The sections that follow will explore how religious revivalism in upstate New York gave birth to (or turbocharged) the temperance crusade, the abolitionist movement, early women’s rights activism, and campaigns for other social improvements like prison and education reform.

The Temperance Movement: Crusade Against Alcohol

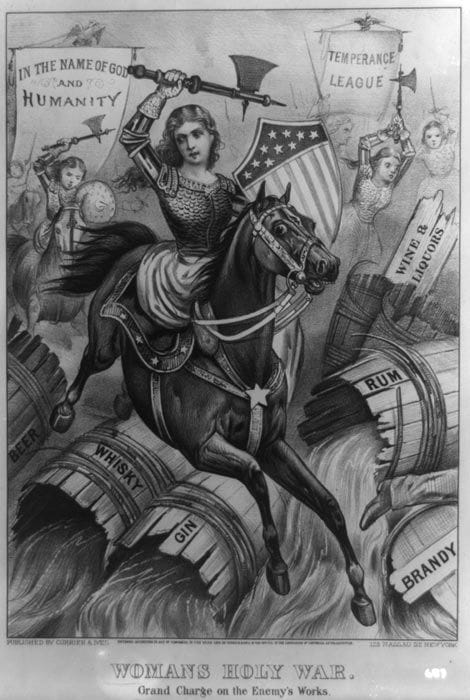

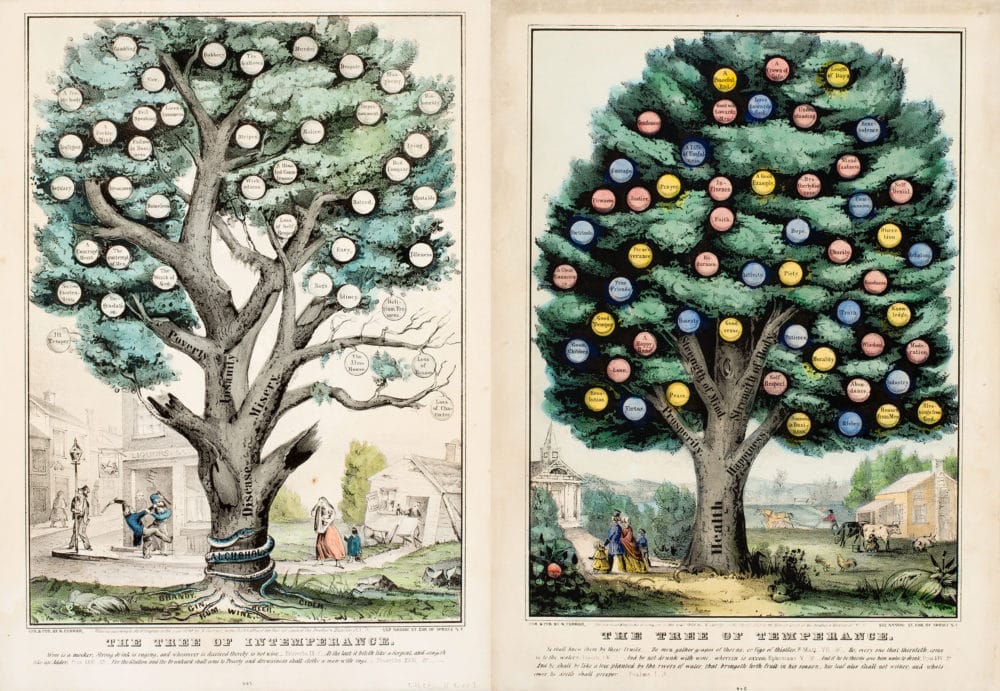

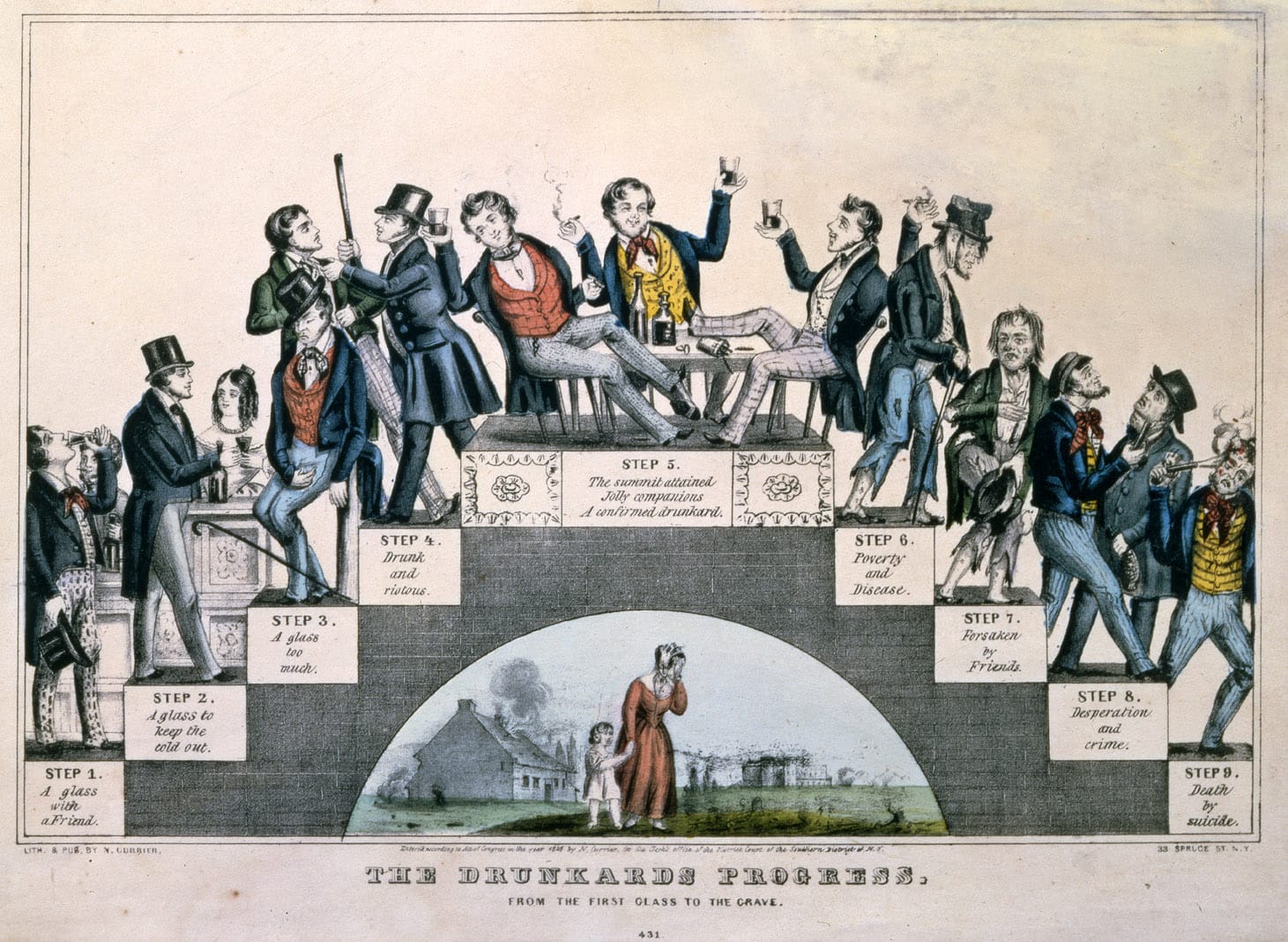

A widely circulated 1820s temperance cartoon, “The Drunkard’s Progress,” dramatized how a single drink could set a man on a downward spiral from The Morning Dram to The Grog Shop and finally to Poverty, Wretchedness & Ruin.Such imagery reflected and reinforced the Burned-Over District’s fervent campaign to eradicate the sin of intemperance.

Of all the moral reform causes energizing the Burned-Over District, temperance – the campaign to curb or abolish the consumption of alcoholic beverages – was one of the earliest and most widespread. To evangelical Protestants, intemperance was not a mere personal vice; it was a scourge on the social fabric, responsible for poverty, broken families, and crime. A popular slogan warned that “strong drink” was not only a devourer of men’s health, but a destroyer of their souls. Ministers thundered from pulpits about the tavern as Satan’s playground. In revival meetings, it was common for preachers to implore new converts to pledge total abstinence as a sign of their repentance. As a result, the temperance movement in upstate New York drew heavily from the ranks of the “born again.” It became, in essence, a practical outworking of revivalist religion: if one truly loved God, one must renounce ardent spirits and help one’s neighbors do the same.

The institutional backbone of the temperance reform was the proliferation of voluntary societies. The American Temperance Society (ATS), founded in 1826, quickly established auxiliaries throughout New York State, including in many Burned-Over District communities[^10]. By the early 1830s, temperance societies in dozens of villages and towns were holding rallies, circulating tracts, and collecting signatures on abstinence pledges. These societies often drew clergy and laypeople together into cooperative action. Presbyterians, Methodists, Baptists, and others set aside sectarian differences to pursue the common goal of sobering up their communities. Local chapters frequently invited traveling lecturers to speak on the evils of alcohol. One such speaker, John Marsh, delivered an impassioned address in Albany in 1832, declaring that “the temples of intemperance shall be torn down by the hands of converted drunkards themselves, and upon their ruins will rise the altars of temperance and virtue.”[^11] Hyperbolic as it was, Marsh’s imagery captured the millennial optimism of the movement – the belief that an era of social purity was within reach.

Temperance advocates in the Burned-Over District employed a variety of tactics, both persuasive and coercive. The earliest phase of the movement relied on moral suasion: temperance orators recounted heartbreaking tales of families ruined by drink, and recovering alcoholics gave moving testimony at meetings (the “Washingtonian” approach beginning in the 1840s, named after a group of reformed drunkards from Baltimore, stressed personal storytelling of redemption). Churches hosted signing ceremonies where men (and sometimes women and youth) would solemnly sign a pledge to abstain from liquor. By the mid-1830s, over a million Americans had taken the temperance pledge, and alcohol consumption nationwide was said to have dropped sharply[^12]. In western New York, entire villages reported closing down their taverns due to lack of patronage, and local newspapers noted a marked decline in public drunkenness. Such changes were a point of pride – tangible evidence that evangelical faith was reforming society.

Before long, the movement’s goals grew more ambitious. Many temperance reformers, convinced by a decade of experience that voluntary abstinence needed the backing of law, began agitating for legal prohibition of alcohol sales. This shift sparked debates within the movement. Some stalwarts argued that any use of state power contradicted the principle of individual moral choice. But others, including a newer generation of activists emerging in the 1840s, believed that liquor traffic was an evil so great it had to be outlawed for the public good. The Burned-Over District saw early experiments in this regard. Several counties in New York adopted local “dry” laws or strict licensing regulations. By 1845, the state legislature was being petitioned by innumerable church groups and temperance societies from upstate towns, all calling for statewide prohibition[^13]. Although New York did not institute a lasting prohibition in the antebellum era (an 1855 dry law was passed but later struck down in court), the pressure from the grassroots was a harbinger of the national Prohibition to come decades later. In fact, many veterans of the 1830s–40s temperance crusade would live to see the 18th Amendment enacted in 1919, a testament to the long-lived influence of the ideals born in that earlier period.

The temperance movement also had significant social side-effects in the Burned-Over District. It fostered new norms of respectability and class identity: sobriety became a hallmark of the up-and-coming middle class, distinguishing them from those of “inferior” habits. Tavern culture, once an accepted part of male social life, now came under heavy stigma in evangelical communities. Historian Carol Sheriff observes that along the Erie Canal corridor (a region overlapping the Burned-Over District), the spread of temperance signified a transformation in socializing practices—workers were encouraged to join temperance meetings and Sunday schools instead of the grog shop, fundamentally altering patterns of leisure and masculinity[^14]. However, this cultural shift sometimes bred resentment. Laboring men, especially recent Irish or German immigrants for whom beer or whiskey was entwined with their heritage and solidarity, often felt targeted and villified by the Protestant temperance crusaders. Thus, while temperance ostensibly aimed at moral uplift for all, it also carried an undercurrent of class and ethnic tension. Nowhere was this more evident than in the cities: in Rochester and Buffalo, “downtown” immigrant districts resisted the dry reform edicts coming from the Yankee church folk on the hill. Such tensions hinted that moral reform could become entangled with nativism – a trend that would grow in the 1850s with the Know-Nothing movement, which had a strong footing in upstate New York as well.

Despite these challenges, the temperance crusade in the Burned-Over District by and large remained a unifying force among native-born evangelicals. It set an example for other reforms by showing how a motivated citizenry could alter the habits of a population through organization, persuasion, and sheer moral pressure. The experience also knit together networks of activists—clergymen, housewives, physicians, lawyers—who would soon turn their attention to the next great moral question facing the nation: slavery. Indeed, there was considerable overlap between temperance advocates and abolitionists. As early as the 1830s, observers noted that the same zealous church ladies who organized temperance teas were collecting signatures against slavery, and the same preachers thundering against rum were also denouncing human bondage from their pulpits. The evangelical drive to purge sin knew no boundaries: once alcohol was attacked, other evils beckoned for extirpation.

Abolitionism: Faith in the Fight Against Slavery

The Burned-Over District became a crucial battleground in the antebellum struggle against slavery. It might at first seem surprising that a region far from the Southern slaveholding states would take a leading role in abolitionism. Yet the very religious convictions that animated temperance found an even higher moral cause in the emancipation of the enslaved. For revival-minded Christians, slavery was not only a political and economic system—it was the ultimate sin of the nation, a violation of God’s law that cried out for redress. Early on, some northeastern evangelicals had supported the Colonization movement (the idea of freeing Black people and “repatriating” them to Africa), seeing it as a moderate anti-slavery strategy. But by the 1830s, influenced by revivalist immediatism (the urgency of now) and the rhetoric of radical reformers like William Lloyd Garrison, many in western New York had embraced immediate abolitionism: the demand for slavery’s immediate end with no compensation to enslavers and full civil rights for Black people. Nowhere outside of New England did abolitionism take stronger root than in the Burned-Over District, which earned another nickname: the “Northern Bible Belt” of anti-slavery activism[^15].

One catalyst was the conversion of key individuals who linked evangelical piety with abolitionist passion. Theodore Dwight Weld is a case in point. Weld attended Finney’s revival meetings in the 1820s and later studied at the Oneida Institute in upstate New York, a hotbed of interracial education and reform. He became one of the nation’s most influential abolitionist agents, training a band of activists (sometimes called “the seventy” or the “Lane Rebels” after an early campaign at Lane Seminary) who spread out to preach against slavery throughout the Old Northwest and Northeast[^16]. Many of these itinerant antislavery lecturers crisscrossed the Burned-Over District during the 1830s, holding meetings in churches, town squares, and barns. They found an eager audience among those who had experienced revival: farmers and villagers whose hearts had been softened to issues of moral conscience. Local anti-slavery societies sprang up like mushrooms after a rainstorm. By 1838, more than 200 antislavery societies existed in New York State, a large proportion of them in the western counties[^17].

Black abolitionists too were central to the movement’s strength in this region. The Burned-Over District was home to a small but vibrant free Black community, especially in cities like Rochester, Syracuse, and Buffalo. These communities established their own churches (often African Methodist or Baptist) which became centers of anti-slavery organizing. One towering figure was Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery and settled in Rochester in 1847. Douglass, a commanding orator and writer, launched his abolitionist newspaper The North Star in that city, declaring as its motto: “Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren.”[^18] That motto, blending women’s rights and anti-racist sentiment with a theological claim of human brotherhood, epitomized the spirit of reform in the Burned-Over District. Douglass drew direct inspiration from the evangelical idea of equality before God. He and other Black activists in upstate New York (such as Jermain Loguen in Syracuse, or Austin Steward in Rochester) worked alongside white abolitionists but also often prodded them to live up to their own ideals. For example, Douglass did not shy from rebuking northern churches that remained complicit in slavery. In an 1848 Independence Day speech in Western New York, he castigated ministers who preached Scripture yet turned a blind eye to the enslavement of millions, calling slavery “an abomination in the eyes of the Almighty” and urging immediate action[^19].

Abolitionist activity in the region ranged from moral suasion to direct action. On the moral suasion side, thousands of petition signatures from upstate New Yorkers, including many women, flooded Congress in the late 1830s and 1840s demanding the end of slavery in Washington D.C. and other federally-controlled territories. Local abolitionist newspapers (such as The North Star and the earlier Albany Patriot) spread anti-slavery arguments drawn from Christian ethics and the ideals of the Declaration of Independence. Antislavery fairs and fundraising events were held, often organized by church ladies, to support the cause and to aid fugitives. This brings us to the direct action: the Underground Railroad. The Burned-Over District, lying just south of Canada, became a critical segment of the clandestine network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. Stations on the Underground Railroad dotted the region; safe-houses were maintained in small towns and rural farms. Both Black and white residents participated, risking fines or imprisonment under laws like the Fugitive Slave Act. In Syracuse, the famous “Jerry Rescue” of 1851 saw abolitionists (reportedly including religious leaders) storm a jail to free a captured freedom seeker, defying federal authority in what they saw as obedience to a higher law (God’s law of justice). Incidents like this underscored the intensity of moral conviction that had taken hold.

Yet abolitionism also encountered staunch resistance and division, even within this reform-minded region. Not everyone who decried alcohol was ready to embrace Black equality. Deep-seated racial prejudices did not vanish overnight among northern whites, revivalist or not. In fact, early abolition meetings in some upstate towns met with violent opposition. The New York Anti-Slavery Society’s founding convention in Utica in 1835 was broken up by a mob of anti-abolition locals (including some respected citizens) who feared the radicalism of the movement. The meeting had to reconvene in a safer location offered by Gerrit Smith, a wealthy evangelical abolitionist, at his estate in Peterboro[^20]. This episode highlighted that even in the Burned-Over District, the anti-slavery cause was initially controversial and had to overcome fear and conservatism. Churches split over the issue: many Presbyterian and Methodist congregations in the 1830s saw factions form between abolitionist members and those who preferred not to mix “politics” with religion. Nationally, major denominations (Methodists and Baptists) formally split into Northern and Southern branches in 1844–45 largely over the slavery question, and the northern segments (which included New York) took a more abolitionist-friendly stance. But even among abolitionists themselves, there were fissures. A significant split occurred in 1840 when the American Anti-Slavery Society divided into factions – one led by William Lloyd Garrison, who pushed for broader reforms (including women’s rights and a strict moral suasion approach), and another more conservative faction (led by the Tappan brothers of New York) that wanted a focus solely on slavery and favored forming a political party. Burned-Over District abolitionists were found on both sides of this divide. Many evangelicals here aligned with the Tappans’ approach, helping to form the Liberty Party in 1840, the first anti-slavery political party, which notably held one of its early conventions in western New York[^21]. Others in the region, including several Quakers and radical Baptist ministers, sided with Garrison’s disunionist, women-embracing wing. Thus the movement contained internal debates about tactics and principles: Should abolitionists enter politics or abstain? Should they endorse equal rights for women and other reforms or keep a single-issue focus?

Despite differences, the abolitionists of the Burned-Over District made an indelible impact on the national anti-slavery struggle. They helped popularize the idea that slavery was a sin to be repented of immediately, not gradually. By the eve of the Civil War, their once “fanatical” position had influenced mainstream northern opinion to view the Slave Power as a threat to the Republic’s moral and democratic foundations. The fusion of revivalist fervor with abolitionism created a potent moral force. An English visitor to upstate New York in the early 1850s remarked that the region’s churches seemed as intent on discussing the slavery crisis as on saving souls, and that sermons often sounded like “abolitionist tracts with scripture sprinkled throughout.” This intertwining of faith and activism in the Burned-Over District would have a long legacy, prefiguring the social gospel movements of later decades. But in the immediate term, it also laid groundwork for another profound societal reform burgeoning in the area – the movement for women’s rights.

Women’s Rights and the Birth of Feminist Activism

In July 1848, a unique convention convened in the little village of Seneca Falls, right in the heart of the Burned-Over District. What brought together a few hundred women and men in the Wesleyan Chapel was not a church revival or an anti-slavery meeting (though many present were veterans of both), but something new under the sun: an organized demand for women’s rights. The Seneca Falls Convention – the first of its kind – issued a bold Declaration of Sentiments proclaiming that “all men and women are created equal” and listing the myriad ways in which women were oppressed by society and law[^22]. The origins of this historic gathering are deeply intertwined with the religious and reform currents of the region. Most of the key organizers were part of families long active in revivalism and moral reform. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the principal author of the Declaration, was the daughter of a judge but also the cousin of Gerrit Smith (the abolitionist) and had been inspired by evangelical perfectionism to believe in human equality. Lucretia Mott, who presided over the convention, was a Quaker minister and veteran abolitionist from nearby (Quakers, with their egalitarian religious doctrine allowing women preachers, provided an important model). Even Frederick Douglass attended, lending his support as a delegate and famously arguing in favor of women’s suffrage. In effect, the women’s rights movement was born out of the convergence of all the prior reform energies of the Burned-Over District – it was the next logical step for those who, in fighting for the souls of drunkards and the freedom of slaves, had begun to see another class of human beings held in bondage: women.

The role of revivalism in shaping early feminism was both inspirational and paradoxical. On one hand, evangelical religion had given women a platform (however limited) for public engagement in the form of ladies’ charitable societies, missionary efforts, and participation in mixed reform groups. Women like Stanton, Susan B. Anthony (who joined the cause a couple of years later in Rochester), and Sojourner Truth (the formerly enslaved Black woman who became a traveling speaker based in western New York) all found their voice initially through moral reform work that was sanctioned by religious norms. Anthony, for example, was drawn into temperance and anti-slavery organizing through Quaker connections and revival-influenced temperance circles in the 1840s. It was while campaigning for temperance that Anthony confronted the stark reality that as a woman she had no voting rights and frequently no voice in meetings—an indignity that propelled her toward the suffrage fight[^23]. Similarly, many of the women who signed the Seneca Falls Declaration had first met in church societies or abolitionist sewing circles. Their reformist credentials lent moral weight to their demands; they could assert that in seeking equality they were fulfilling God’s will of justice, having already helped achieve righteous causes like temperance and abolition.

On the other hand, the women’s rights movement quickly exposed tensions with the very religious establishment that had nurtured reform. The bold notion of women’s equality was too radical for many clergymen, including some erstwhile allies in temperance or anti-slavery work. After Seneca Falls, a number of ministers (including some in the Burned-Over District) denounced the women’s rights advocates for stepping outside the Biblically prescribed role of women. Even within the reform community, there was division: the convention’s call for women’s suffrage (the right to vote) nearly failed because some attendees – including even the progressive Quaker James Mott – initially thought it too extreme. It passed largely thanks to Frederick Douglass’s eloquent support, linking the cause to fundamental American ideals. But this incident underscored an important point: support for women’s rights was not universal among reformers; it had to overcome ingrained sexist attitudes. Many abolitionist men who readily accepted women’s help in abolition still balked at the idea of women’s full equality. Stanton and Mott had experienced this firsthand in 1840, when they were barred from sitting as delegates at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London because of their sex – a snub that helped galvanize their resolve to start a women’s movement. In the Burned-Over District, some abolitionist groups and churches split over whether to endorse women’s rights, just as they had over slavery. For instance, in Rochester, a prominent minister, Rev. Asahel Nettleton, preached against the “infidel womanism” of the Seneca Falls women, causing controversy in his congregation[^24].

Despite resistance, the early women’s rights movement gained remarkable momentum in upstate New York. After Seneca Falls, additional conventions were held in Rochester (also in 1848, just two weeks later) and in subsequent years across the state. Women’s activism took many forms: petition campaigns for married women’s property rights and suffrage; the formation of women’s temperance societies (since temperance remained a more socially acceptable arena, some activists tackled women’s issues under that guise – e.g., Amelia Bloomer of Seneca Falls started The Lilyin 1849 as a temperance journal, which soon began advocating women’s dress reform and rights); and a flurry of local speaking engagements by figures like Stanton, Anthony, and Lucy Stone. It’s noteworthy that this movement was intergenerational and, to a degree, interracial. White middle-class women led the charge, but they drew inspiration from the oratory of Black women like Sojourner Truth, who famously addressed a women’s rights meeting in Akron, Ohio in 1851 with her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. Truth, who had spent years in a utopian religious community in Harmonia, NY (near Buffalo), brought together religious fervor and feminist insight, pointing out the double burden carried by Black women[^25].

The Burned-Over District’s cultural climate helped the women’s movement in subtle ways. The prevalence of perfectionist theology – the idea, popular in Finneyite circles, that it was possible to strive for a state of moral perfection – encouraged reformers to believe that all forms of inequality and sin could be overcome. Some women’s rights advocates, such as Gerrit Smith’s daughter Elizabeth Smith Miller, explicitly argued that if society could purge the great sins of intemperance and slavery, why not the sin of women’s subjugation? This moral reasoning framed sexism as another social ill to be remedied by Christian ethics. Not all supporters of women’s rights were conventionally religious (Stanton herself grew critical of organized religion’s treatment of women and later in life authored The Woman’s Bible commenting on misogynistic scriptural interpretations), but even the more skeptical drew on the moral capital accumulated by revivalism. They could appropriate the language of natural rights and divine justice that had filled the sermons of the Awakening. In doing so, they gave the women’s movement a strong ethical foundation.

By the 1850s, the women’s rights cause in New York had secured some concrete victories. In 1848, the New York State Married Women’s Property Act was passed, thanks in part to years of pressure from women reformers (allowing married women to own property and wages in their own name). This was one of the first laws of its kind in the U.S. and was celebrated by activists as an important step. However, suffrage – the ultimate goal – remained elusive until many decades later. The Civil War in 1861 would put a pause on the women’s rights conventions as national attention turned to the conflict over slavery. But the networks and ideas forged in the Burned-Over District pre-war period laid the groundwork for the next wave of feminism after the war. Ironically, that later period saw a bitter split between some former allies: when the 15th Amendment in 1870 granted voting rights to Black men but not to women, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (both with deep roots in the Burned-Over District’s reform culture) opposed it, arguing for universal suffrage instead. Frederick Douglass and other abolitionist colleagues disagreed, urging support for Black men’s enfranchisement even if women had to wait. This episode highlighted how even shared revivalist beginnings could diverge into conflict – an echo of the earlier tensions within reform movements, now played out on a national stage[^26]. Such schisms notwithstanding, the collaboration of abolitionism and early feminism in upstate New York remains one of the hallmark achievements of the Burned-Over District’s legacy.

Reforming Prisons, Schools, and Other Institutions

Alongside the headline causes of temperance, abolition, and women’s rights, revivalist social concern in the Burned-Over District also fostered improvements in education, prisons, and care for the needy. The same ethic of Christian stewardship that motivated crusades against liquor and slavery led many in the region to ask how society might treat its most vulnerable and neglected members more humanely. In the 1820s and ’30s, New Yorkers were among the pioneers of what came to be known as the penitentiary movement – a radical rethinking of criminal punishment. The traditional county jails, which merely detained people in squalor without reform, were seen as failing both morally and practically. Influenced by Quaker and Protestant ideals of human perfectibility, reformers advocated for penitentiaries where convicts would undergo rehabilitation through disciplined routine, labor, and religious instruction. The famous Auburn Prison in central New York became a model: it developed the “Auburn system” in which prisoners worked silently in groups by day and were isolated in cells at night, with an emphasis on strict order, Bible study, and penitence. Evangelical chaplains like Rev. Jared Curtis at Auburn believed that even criminals had souls worth saving, and they sought to reduce recidivism by instilling habits of industry and prayer[^27]. The state of New York embraced these ideas, opening Sing Sing Prison (downstate) on similar principles and appointing clergymen to oversee inmate moral welfare. Citizens of the Burned-Over District took pride in these innovations, sometimes touring the new facilities as evidence that society could elevate even its lowest members. Local prison reform societies collected donations of Bibles and tracts to distribute among inmates. In 1844, the New York Prison Association was founded (with several upstate reformers on board) to monitor conditions and advocate further improvements, reflecting the ongoing commitment to this cause.

Education reform was another arena where the Burned-Over District’s communities showed leadership. Western New York in the early 1800s was still a frontier in terms of schooling—many areas had only rudimentary one-room schoolhouses or depended on parents to teach at home. But the wave of reform brought an insistence that ignorance was also a social sin to be combated. Evangelicals championed the creation of common schools (free public schools) as a means to teach not only literacy and arithmetic but also moral values and the Protestant work ethic. In the 1830s and ’40s, under the influence of figures like Horace Mann (in Massachusetts) and Gerrit Smith (in New York), states began to establish more structured public school systems. New York State passed a series of common school laws and by 1849 had authorized free schooling for all children — a landmark move[^28]. In the Burned-Over District, where towns were often fiercely proud of their churches and civic institutions, citizens threw themselves into building schools and academies. Women played a significant role here too: Catharine Beecher (Lyman Beecher’s daughter, though she operated more in the midwest later) and Emma Willard were advocates of women’s education with ties to New York. Willard in fact opened the Troy Female Seminary in 1821 (in eastern NY) to provide advanced education for young women, a model that influenced thinking in the West. Closer to the Burned-Over region, Oberlin College just over the border in Ohio – closely linked to Finney and Burned-Over revivalism – became in 1837 the first U.S. college to admit women alongside men and one of the first to admit Black students as well[^29]. Oberlin’s example sent a powerful message back to upstate New York about coeducation and equal opportunity, reinforcing local efforts to expand schooling. By mid-century, upstate New York boasted numerous academies, teacher-training institutes, and literary societies, reflecting the zeal for learning. The lyceum movement, which organized public lectures for adult education, also thrived in the region’s towns, offering laypeople exposure to new ideas and scientific knowledge – all in line with the belief that an enlightened, moral citizenry was attainable.

Other reform endeavors touched the lives of the poor, the sick, and the mentally ill. The 1830s saw the rise of charity organization societies and the construction of orphan asylums and poorhouses, often with women reformers at the helm of committees. In this, as in other areas, there was a mix of compassion and social control: evangelicals wanted to rescue individuals from vice and misery, but they also wanted to instill discipline and industry. For example, the New York Female Moral Reform Society, though based in New York City, had auxiliary chapters in the Hudson Valley and possibly in some Burned-Over District towns. Founded in 1834 by evangelical women, its mission was to combat prostitution and sexual sin by rescuing “fallen women” and lobbying for laws against seduction and brothel-keeping. While its greatest strength was in urban areas, the ethos – that female virtue must be protected and that male licentiousness must be curbed – resonated with upstate morals. It was another outlet for women to participate in public moral policing, and it dovetailed with the temperance message of male self-restraint. Meanwhile, care for the mentally ill was dramatically reformed through the efforts of Dorothea Dix, a Bostonian who in the 1840s toured jails and almshouses across states (including New York) and exposed the horrid conditions in which the insane were kept. New York, influenced by such advocacy and by Quaker experiments in moral treatment, established state lunatic asylums (such as the Utica State Asylum, opened 1843) that aimed to provide more humane treatment – quiet surroundings, meaningful occupation, and kindness rather than chains. These developments, while not unique to the Burned-Over District, found fertile ground there because the populace was already sensitized to moral and social improvement campaigns.

Tensions and Legacies of Reform in the Burned-Over District

By mid-century, the Burned-Over District had earned its reputation as a wellspring of reform, but it also bore the marks of tensions and contradictions that complicated the legacy of the Second Great Awakening. One recurring tension was between idealism and social reality. The evangelical reformers often preached an ideal of human brotherhood and equality under God, yet in practice, their movements did not always live up to those values. For instance, many temperance and anti-prostitution initiatives implicitly targeted the working class and immigrants, reflecting a paternalistic attitude as much as altruistic concern. A poor Irish laborer reeling from economic insecurity might have resented being told by moralistic neighbors to give up the solace of whiskey. Thus, what reformers saw as benevolent uplift, others sometimes saw as an intrusion into personal freedom or an attack on their culture. These class and ethnic fault lines occasionally erupted in conflict – be it a tavern brawl over temperance or a street confrontation between “nativist” reformers and immigrant communities. The reformers, confident in their righteousness, sometimes failed to grasp why their agenda was not universally embraced.

Another tension lay in the realm of race and gender within the movements themselves. While abolitionism in the Burned-Over District was interracial in theory and often in practice, white abolitionist leaders did not always accord Black colleagues equal authority. Frederick Douglass, despite his prominence, sometimes had to contend with white patrons who preferred that Black activists “know their place” (for example, Douglass’s break with William Lloyd Garrison’s circle involved, in part, Douglass asserting editorial independence for his own newspaper). Black women were even more marginalized – figures like Sojourner Truth were celebrated as orators, yet the institutional leadership of the movements remained overwhelmingly in white male hands. In the women’s rights sphere, an analogous issue emerged: white middle-class women led the charge and tended to focus on issues most pertinent to their own experience (like property rights and suffrage). Women of color or working-class women had different, often harsher, experiences that got less attention. Even some progressive women harbored racial prejudices; during the post-Civil War suffrage debates, Stanton infamously made racist-tinged arguments about educated white women deserving the vote over ignorant ex-slaves[^26]. These cracks did not yet fully fracture the coalition in the 1840s, but they were present under the surface.

Religious enthusiasm itself sometimes clashed with emerging secular ideas. By the 1850s, a younger generation in the North was beginning to be influenced by transcendentalism, science, and liberal thought, which made them a bit skeptical of the old-time revival spirit. In cities like Rochester, you could find Unitarian lectures or “free thought” meetings that would have been anathema a generation prior. Some critics of the pervasive reform culture derided the Burned-Over District as a haven of “fanaticism” – a word frequently used in newspapers of the time to belittle those seen as extreme. For example, conservative editors mocked the region’s activists as “fanatics of abolition and women’s nonsense” who disrupted the social order. Even within churches, the revival tradition faced pushback by the 1840s from those who felt it had gone too far in emotionalism and in merging religion with political causes. A kind of reform fatigue set in for some folk, who longed for a return to “normalcy” and old-fashioned social pleasures without guilt.

Yet, despite these undercurrents, the overall trajectory set in the Burned-Over District was one of progressive change that outlived the antebellum period. The Civil War (1861–65) would, of course, bring the slavery question to a fiery resolution on the battlefield, but one cannot overlook the role that decades of moral agitation in places like upstate New York played in shaping the Northern conscience that was necessary to sustain that war for Union and emancipation. Many of the Union’s political and military leaders – from President Lincoln to General Ulysses S. Grant – commented on how the evangelical churches created the moral climate that made abolishing slavery a non-negotiable war aim. When Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe (daughter of Lyman Beecher, though the Beechers were more New England), he allegedly quipped, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war,” referencing Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe’s novel, though not a product of the Burned-Over District per se, was part of the same reformist culture; her family’s temperance and revival background influenced her antislavery storytelling. In short, the revival-born reform ethos helped set the nation on a course to confront its gravest sins.

After the Civil War, the momentum of reform continued in new forms. The temperance movement resurged with the formation of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in the 1870s, led by none other than Frances Willard – a Midwesterner, but one notably inspired by the earlier generation of temperance women from places like upstate New York. Willard’s WCTU broadened temperance into a comprehensive women’s reform network, championing suffrage and social purity, and it owed an intellectual debt to the Burned-Over District’s fusion of piety and activism. Meanwhile, veterans of the Seneca Falls era like Susan B. Anthony continued the fight for women’s suffrage, which was finally achieved in 1920 with the 19th Amendment – a victory that had its symbolic first spark in that 1848 chapel gathering. The fact that Seneca Falls is today celebrated as the birthplace of women’s rights in America underscores the enduring significance of what transpired in this region.

Perhaps the most profound legacy of the Burned-Over District is the model it provided for grassroots social action rooted in moral conviction. Time and again, American history would see religious or ethical movements rise to challenge injustices – from the Social Gospelers who, a few decades later, tackled industrial exploitation and poverty, to the Civil Rights activists of the 1950s–60s who sang church hymns as they marched against segregation. In many ways, those later movements drew from a template first crafted in the burned-over hills and towns of western New York: raise popular awareness, form societies and conventions, publish tracts, petition the government, and appeal to the nation’s conscience, all undergirded by a belief in higher principles and, often, divine sanction.

Conclusion

The Burned-Over District during the Second Great Awakening was a remarkable proving ground for the American experiment in social reform. Here, on what was once the fringe of settlement, communities were forged in the white heat of revivalism and then reshaped by a determination to redeem society as well as souls. The social fabric of the region—its family life, gender norms, community bonds, and class structure—was transformed as religious revival spilled into moral reform. A spirit of volunteerism and grassroots democracy flourished, with citizens banding together to fight what they saw as the sources of human misery and sin. They took on alcohol abuse, human bondage, the rights of women, the plight of prisoners, the needs of the ignorant and poor, and more. In doing so, they redefined the relationship between the individual and society: personal faith became a mandate for public service.

The movements that emerged in the Burned-Over District were far from perfect. They carried biases of their time, grappled with internal dissent, and sometimes imposed as much as they liberated. Nonetheless, their impact was profound and lasting. The temperance crusade pioneered methods of mass mobilization later used in various “moral wars,” and it left temperance ideals ingrained in American culture. The abolitionists of western New York helped shift the national moral compass against slavery, tilting the political balance toward liberty and Union. The women’s rightsadvocates at Seneca Falls lit a flame that, though it flickered and faced storms, would never be fully extinguished until women achieved equal citizenship. And the quieter revolutions in education and institutional care showed a faith in progress—that humane policies could make for a more just and enlightened society.

In sum, the intense religiosity of the Burned-Over District drove social change by linking the salvation of the individual to the salvation of the community. It was a place where ordinary farmers, housewives, and preachers fervently believed they could remake the world in God’s image—and in some measure, they did. The reverberations of their zeal echo through American history. As we reflect on this legacy, we see that the Burned-Over District’s story is not just a regional or denominational tale, but a quintessentially American one: it illustrates how the nation’s greatest reforms often sprang from the nexus of moral conviction and collective action. In the fiery crucible of revival and reform, a new vision of society was kindled—one that continues to inspire and challenge us even today.

[^1]: Charles G. Finney, Lectures on Revivals of Religion (New York: Leavitt, Lord & Co., 1835), 264. Finney declared that Christians must shape politics and society, or else “God will bless or curse the nation” accordingly, indicating his view that revivalism carried an obligation for social action.

[^2]: Whitney R. Cross, The Burned-over District: The Social and Intellectual History of Enthusiastic Religion in Western New York, 1800–1850 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1950), 13–15. Cross describes the close-knit evangelical communities and the reformist impulse that naturally followed the revivals.

[^3]: Paul E. Johnson, A Shopkeeper’s Millennium: Society and Revivals in Rochester, New York, 1815–1837 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978), 113–117. Johnson analyzes how Rochester’s revival united middle-class proprietors in a campaign for social order and helped instill temperance and Sabbatarian values among the working class.

[^4]: Mary P. Ryan, Cradle of the Middle Class: The Family in Oneida County, New York, 1790–1865 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 3–5, 184. Ryan details how evangelical religion in Oneida County shaped a new middle-class culture centered on domesticity, piety, and female moral influence in the family.

[^5]: Charles G. Finney, Memoirs of Rev. Charles G. Finney (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1876), 78–79. Finney notes instances of women leading prayer in his meetings, a practice he permitted as part of his “new measures,” which was innovative for the time and stirred some controversy among traditionalists.

[^6]: Nancy F. Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman’s Sphere” in New England, 1780–1835 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 119–123. Cott’s analysis of the cult of domesticity, although focused on New England, illuminates the notion of women as moral guardians in the home—a concept that was equally influential among evangelical families in New York.

[^7]: Nancy A. Hewitt, Women’s Activism and Social Change: Rochester, New York, 1822–1872 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984), 35–40. Hewitt documents how converted women in Rochester used church networks to found female charitable societies and later pivoted to reform causes like abolition and suffrage, developing organizational and leadership skills in the process.

[^8]: “Circular Letter: The General Association of Massachusetts to the Churches Under Their Care,” Boston Recorder, July 1837. This so-called “Pastoral Letter” cautioned women against usurping the role of men by speaking in public, reflecting a backlash from clergy when women began taking visible roles in abolitionist meetings.

[^9]: Weld’s emphasis on opposing all sin can be found in his correspondence and speeches; see for example Theodore D. Weld, “Speech at the Church of the Puritans,” New York, May 1854, in the Liberator (June 2, 1854), where he insists that a true Christian must “feel as keenly for the enslaved African as for his own soul’s salvation,” illustrating the moral imperative revivalists felt to combat slavery.

[^10]: Seventh Annual Report of the American Temperance Society (Boston: Perkins & Marvin, 1834), 10–12. The report lists hundreds of new local temperance groups formed in northern states and notes particularly rapid growth in New York, crediting revivalized churches for the swell in membership.

[^11]: John Marsh, An Address on Temperance (Albany, 1832), 7–9. Marsh, a prominent temperance lecturer and clergyman, used religious millennial language to predict the overthrow of “intemperance” and the triumph of godliness; this address was reprinted in several New York newspapers in 1832.

[^12]: W.J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 234. Rorabaugh notes that per capita alcohol consumption in the U.S. dropped from about 7 gallons in 1830 to under 3 gallons by 1840, and attributes much of this decline to the influence of the temperance movement.

[^13]: New York State Legislature, Journal of the Assembly, 67th Session (1844), 234–237. This record shows petitions from citizens of Monroe, Onondaga, and Oneida counties urging a prohibition law; throughout the 1840s such petitions increased, demonstrating growing political engagement of temperance advocates in the Burned-Over District.

[^14]: Carol Sheriff, The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress, 1817–1862 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996), 173–175. Sheriff discusses how canal towns saw shifts in social life due to evangelical influence, including temperance efforts that attempted to replace the traditional tavern-centered socializing of boatmen and laborers with more orderly, family-oriented activities.

[^15]: James D. Essig, The Bonds of Wickedness: American Evangelicals Against Slavery, 1770–1808 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982), 152. While Essig’s study covers an earlier period, he notes that the revivalist ethos later re-emerged in the 1830s to galvanize anti-slavery sentiment in areas like upstate New York, which contemporaries referred to as a “Bible Belt” of abolitionism.

[^16]: Benjamin P. Thomas and Stacey M. Robertson, Hearts Beating for Liberty: Women Abolitionists in the Old Northwest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 21. This work references Weld’s “Seventy” – a cohort of activists trained in the 1830s – and mentions that many hailed from or were educated in central New York, spreading revival-influenced abolitionism westward.

[^17]: Beriah Green, Report on the Condition of the People of Color in the State of New York (Utica, 1839), 5. Green, president of the Oneida Institute, compiled data on anti-slavery societies and noted the proliferation of local chapters in upstate New York by the late 1830s, indicating strong grassroots support for abolition.

[^18]: The North Star (Rochester, NY), vol. 1 no. 1, December 3, 1847. The masthead of Frederick Douglass’s newspaper proudly declares the motto “Right is of no Sex—Truth is of no Color—God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren,” encapsulating the paper’s commitment to abolition and equal rights, including women’s rights.

[^19]: Frederick Douglass, “Love of God, Love of Man, Love of Country,” speech delivered at a meeting in Buffalo, NY, August 1848, in Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings, ed. Philip S. Foner (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1999), 204–210. In this speech, Douglass invokes religious themes, calling slavery “an abomination” before God and urging moral resistance; it illustrates how Douglass blended revivalist rhetoric with abolitionist argument.

[^20]: Milton C. Sernett, North Star Country: Upstate New York and the Crusade for African American Freedom(Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2002), 45–47. Sernett recounts the disruption of the 1835 Utica anti-slavery convention by a mob and the subsequent removal of the meeting to Gerrit Smith’s estate, highlighting both the opposition abolitionists faced and the support from reform-minded evangelicals like Smith.

[^21]: Gerald Sorin, The New York Abolitionists: A Case Study of Political Radicalism (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1971), 81–84. Sorin explores the emergence of the Liberty Party in upstate New York and notes that many of its organizers were deeply religious and from burned-over counties; they saw political action as a necessary extension of their moral campaign against slavery.

[^22]: Report of the Woman’s Rights Convention, Held at Seneca Falls, N.Y., July 19th and 20th, 1848 (Rochester: John Dick, 1848), 6–7. The Declaration of Sentiments, drafted chiefly by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, is printed in this report; it famously opens by asserting women’s equality in the words modeled after the Declaration of Independence, a radical statement of principles arising from the convention.

[^23]: Elisabeth Griffith, In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984), 45–46. Griffith describes how Susan B. Anthony’s early experiences in the temperance movement (particularly being denied the chance to speak at a temperance meeting because she was a woman) galvanized her to join forces with Stanton in pursuing women’s suffrage.

[^24]: Kenneth E. Middleton, “The Seneca Falls Convention: A Study of Social Networks,” New York History 69, no. 1 (1988): 77–78. Middleton notes that after the Seneca Falls Convention, some clergymen in western New York, such as Rev. Asahel Nettleton, vocally opposed the women’s rights movement from their pulpits, reflecting the backlash in religious circles even within the reformist Burned-Over region. (Nettleton’s criticism is documented in local church records and contemporary accounts).

[^25]: Nell Irvin Painter, Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 128–131. Painter narrates Sojourner Truth’s involvement in early women’s rights meetings and her famous 1851 speech, underscoring how Truth’s identity as a Black woman and former slave brought intersecting perspectives on race and gender to the predominantly white women’s movement, sometimes challenging and broadening its scope.

[^26]: Ellen Carol DuBois, Feminism and Suffrage: The Emergence of an Independent Women’s Movement in America, 1848–1869 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978), 171–175. DuBois discusses the post-Civil War schism between Stanton/Anthony and Douglass/others over the Fifteenth Amendment, highlighting how the conflict was rooted in differing priorities and, regrettably, racially charged rhetoric from some women’s rights leaders – a tension foreshadowed by earlier strains in the alliance between abolitionism and women’s suffrage.

[^27]: Robin L. Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic (Boston: Little, Brown, 1971), 82–87. Rothman examines the Auburn prison system as a prototype of evangelical-influenced prison reform, describing how religious discipline and the promise of redemption for inmates were central to the experiment; New York’s model was widely copied by other states in the antebellum period. (Note: The author’s first name appears to be cut off in the text; it should read “David J. Rothman.”)

[^28]: Lawrence A. Cremin, American Education: The National Experience, 1783–1876 (New York: Harper & Row, 1980), 272–274. Cremin recounts the development of New York’s common school system, noting the 1849 law establishing free public education, and credits the advocacy of reformers in the 1830s-40s (including religious figures and philanthropists) for this achievement in the context of democratic and evangelical values.

[^29]: John H. Miles, “Oberlin Collegiate Institute and the Influence of New York’s Burned-Over District,” Ohio History Journal 79, no. 1 (1970): 50–52. Miles discusses how revivalist Charles Finney’s move to Oberlin College and the school’s admission of women and Black students were partly a product of influences from western New York’s progressive religious culture; Oberlin’s policies in turn reverberated back to inspire educators and churches in New York.